JPMorgan vs. U.S. Virgin Islands: A rather unsettled settlement

- Felix Salmon, author ofAxios Markets

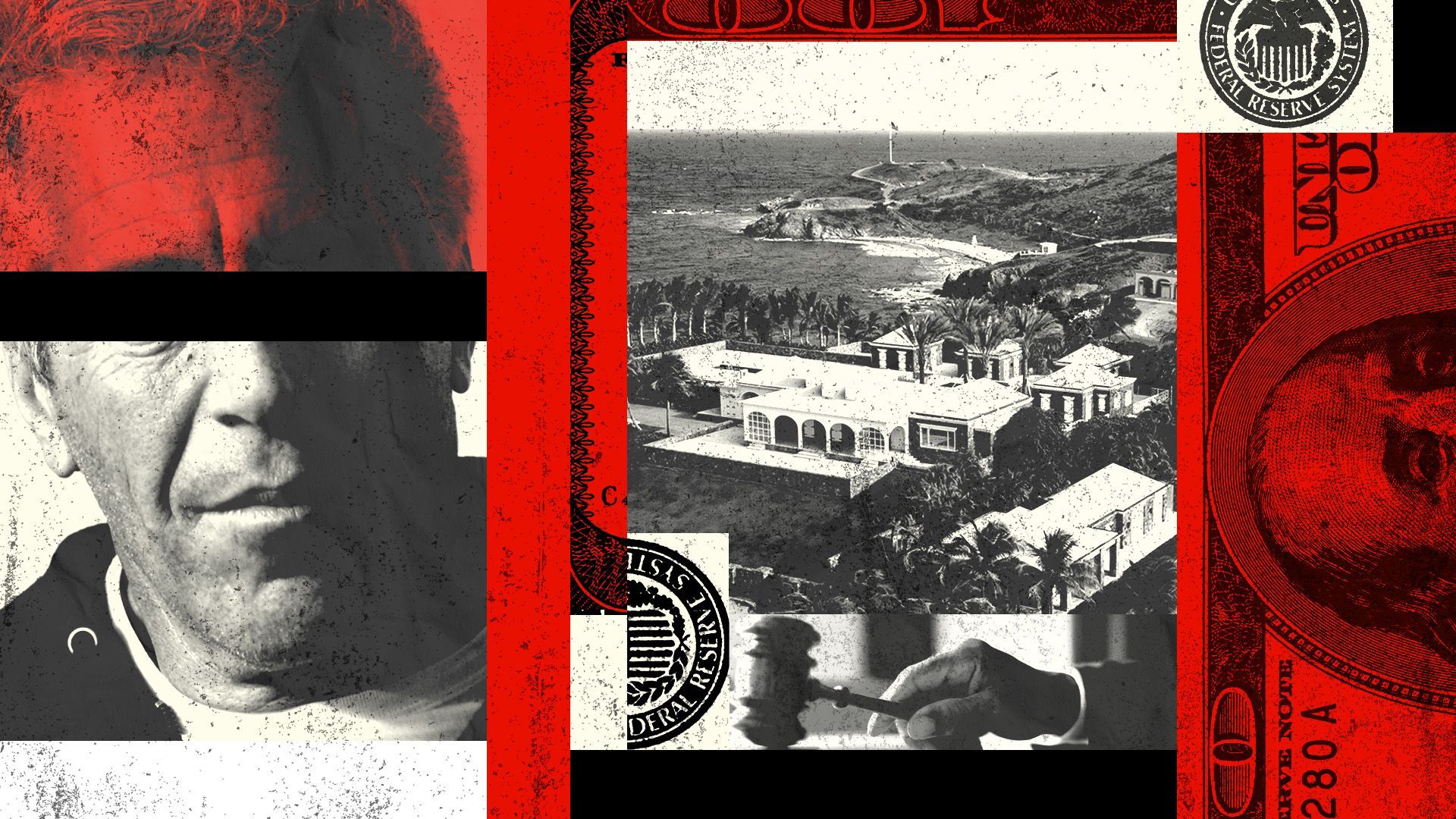

Photo illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios. Photo: Rick Friedman and Emily Michot/Miami Herald/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

When one of the biggest banks in the world announces a legal settlement with a government agency, normally both sides can at least agree on what is being announced. That wasn't the case earlier this week in the matter of Government of the U.S. Virgin Islands v. JPMorgan Chase Bank.

Why it matters: According to the bank, it simply settled a civil lawsuit out of court — something it does on a regular basis — and did not admit any liability.

- According to the Virgin Islands, the U.S. government has for the first time enforced a sex-trafficking law in a historic and trailblazing settlement that will cause profound changes across the banking world.

The big picture: The lawsuit, which the U.S. Virgin Islands filed under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), alleged that JPMorgan facilitated Jeffrey Epstein's sex-trafficking venture not only by banking Epstein and allowing him to withdraw some $1.75 million in cash for payment to his victims, but also by banking the victims themselves.

- Those victim-clients included one woman who had been identified in the press as early as 2006 — seven years before JPMorgan finally broke ties with Epstein — as being his self-described "Yugoslavian sex slave."

Flashback: JPMorgan separately agreed in June to pay $290 million to settle a class-action suit from Epstein's victims that was brought under the same statute.

The intrigue: JPMorgan claims the lawsuit settled this week for $75 million "was not an enforcement action," per spokesperson Trish Wexler. "The USVI was a civil plaintiff in a civil lawsuit," she says.

- The U.S. Virgin Islands, by contrast, describes the suit as "the first enforcement action filed against a bank for facilitating and profiting from human trafficking."

Between the lines: At stake is the question of whether U.S. Virgin Islands attorney general Ariel Smith, acting as a law enforcement officer, extracted promises from JPMorgan to implement new policies ensuring, among other things, that a client's account is terminated if the bank has credible information that the account is facilitating human trafficking.

- Smith says that's exactly what she did. "As part of the settlement, JPMorgan has agreed to implement and maintain meaningful anti-trafficking measures," said Smith in her press release, which goes on to detail "several substantial commitments by JPMorgan Chase," including "establishing and implementing" a series of policies and procedures.

- In terms of those commitments, "likely none of this would have happened without these cases coming forward," Bridgette Carr, the director of the human trafficking clinic at Michigan Law and an expert witness for the U.S. Virgin Islands, tells Axios.

- The settlement "should sound the alarm on Wall Street about banks' responsibilities under the law to detect and prevent human trafficking," says Smith.

The other side: JPMorgan's Wexler tells Axios that while the settlement agreement lists various "previous and ongoing efforts" to fight human trafficking, "there are no new commitments" in the agreement.

- What's more, according to parts of the agreement seen by Axios, the listed commitments are explicitly described as "ongoing good faith efforts" on the part of the bank — and explicitly are "not contractual commitments."

In the weeds: Under the terms of the TVPA, a state attorney general can bring a civil action as "parens patriae" on behalf of residents of the state.

- Parens patriae is a legal doctrine that gives states standing to file a civil lawsuit on behalf of a victim or (as in this case) a class of victims.

- "Any individual victim really can’t speak to the systemic issues," says Carr. That means it's the parens patriae clause, as added to the statute in 2018, that gives AGs the power to craft far-reaching settlements that extend beyond harm done to individuals.

Zoom out: The Epstein case is a stark reminder that traffickers tend to be the kind of wealthy individuals who are very close to their private bankers.

- The best way for a bank to identify such individuals is not to use AI algorithms trained to sniff out suspicious activity. Rather, it's simply to act on the pre-existing knowledge of its client-facing bankers — the kind of people who, in the case of JPMorgan, would email each other about the number of "nymphettes" at Epstein's residence.

My thought bubble: Even if it doesn't have a lot of teeth, the settlement does a very good job of laying out the kind of actions and policies that a truly committed anti-trafficking bank would adopt.

- JPMorgan's refusal to even mention those commitments in its press release, however, suggests that, like all other big banks, it is far from being a full-throated leader in the war against trafficking.