How sluggishness killed Sears

- Erica Pandey, author ofAxios Finish Line

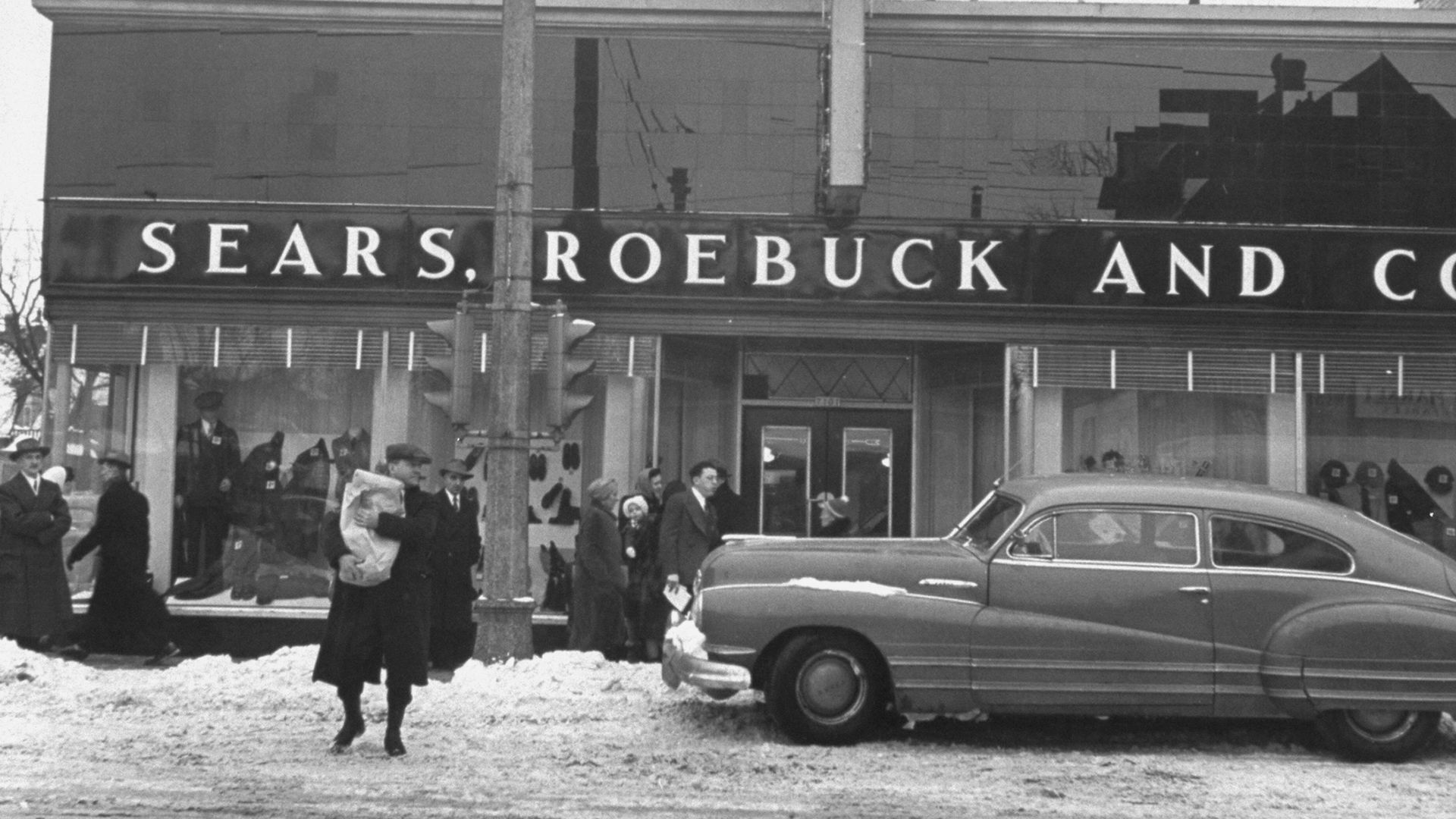

Sears in 1943, the good old days. Photo: Gordon Coster/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Like the rest of Big Retail, Sears thrived for a century and a half on a low-wage, low-productivity strategy, hiring thousands of workers to wade through mountains of inventory and stock shelves. But its practice of sluggishness finally caught up it, as the company today filed for bankruptcy with plans to close another 142 stores.

Why it matters: Brick-and-mortar retail still rakes in a whopping majority — 91% — of shopping dollars. But Sears' fate is the latest and perhaps most dramatic example of how, since 1990, the productivity of department stores has stayed remarkably flat, while online shopping has surged.

- As if to punctuate Sears' plummet, major shareholder Eddie Lampert kept up his show of seeking the best for the chain — stepping down as CEO while remaining as chairman.

The background: Sears' bankruptcy filing comes after a decades-long decline, during which a retail empire of about 3,500 stores in the U.S. and Canada and some 350,000 workers shrunk to 700 — mostly unprofitable — outlets and 68,000 employees. As the company bled assets, it saw a plunge in sales and productivity, which in retail is a ratio of sales to employee hours worked.

- The company underinvested in sprucing up its stores. Instead, it broke into fashion and beauty, banking and real estate, becoming bloated. Meanwhile, it neglected its flagship brands — its big-selling Kenmore appliances, Diehard batteries and Craftsman tools, the latter two of which Lampert sold off.

- "Their locations have become obsolete, and their product mix is no longer adequately differentiated," said Herb Kleinberger, a professor of retail at NYU's Stern Business School.

- "The missteps arguably go back to the 1980s, when Sears became too diversified and lost the deftness that had once made it the world’s largest and most innovative retailer," Neil Saunders, a retail analyst at GlobalData, wrote today in a note to investors.

Cautionary tales from Sears and Barnes & Noble have big-box retailers spooked.

- Sears' 20th century competitors — Walmart, Target and Macy's — are pouring money into refurbishing their stores. They're accepting some short-term pain in exchange for longevity, Saunders tells Axios. "At Sears, it has always been about short-term survival."

- Walmart, Target and Macy's "are not going to be as productive as they once were, and they might never be as productive as Amazon. But they're doing the right things to stay relevant to customers."

The flip side: Amazon just fired a shot across the bow by raising its minimum wage to $15 per hour, showing traditional retailers — many of whom are barely getting by paying workers $10 an hour — that it's doing well enough to afford the bump.

"Amazon is changing the whole supply chain, and retailers who say, 'Don't wake me up,' are in trouble. Anybody who sticks with their old business model is going to be run over."— Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute, a D.C. think tank

As is clear from the chart above, online shopping is shattering ceilings. And the disruption runs deeper than productivity, says Stern's Kleinberger.

- Big-box stores also aren't aligned with how younger consumers shop, he says. In a March 2017 eMarketer survey, 78% of 18-29 year-olds said they prefer to shop online.

- Online shopping has only 9% of the overall retail pie, but some product categories have seen much greater penetration. Amazon has about half the market share for print books, toys and baby products, for instance.

Worth noting: Some brick-and-mortar chains have quickly shifted gears as Amazon continues to disrupt retail — and they're thriving.

- Williams Sonoma, the kitchenware company that's popular in malls across the country, has modernized its supply chain and does 52% of its sales online, per market research firm CBRE.

- Two high-end department stores, Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom's, have seen sluggish in-store sales, but have grown their online businesses to 25% of all sales.