June 01, 2023

Thanks for reading Axios Science. This week's newsletter is 1,622 words, about a 6-minute read.

- We're arriving in your inbox a little later than usual today so we can include details about the poem NASA will fly to Jupiter's moon Europa.

- Send your feedback and ideas to me at [email protected].

- Sign up here to receive this newsletter.

1 big thing: Earth's microbial diversity may be underestimated

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

A two-year expedition to coral reefs in the Pacific Ocean detected half a million types of microbes, the latest estimate in the quest to quantify the planet's microbiome.

The big picture: There is intense debate among scientists about how many different types of bacteria and other microorganisms live on Earth — information that could aid conservation of species and fragile ecosystems brimming with biodiversity.

- The microbiome supports other life on Earth through symbiotic relationships that provide nutrients, protects its hosts from pathogens and performs other essential roles.

- Past efforts to characterize the microbiome have largely focused on a single species or a particular area. But there is a trend toward trying to do large-scale projects, says Emiley Eloe-Fadrosh of the Department of Energy's Joint Genome Institute.

- The crowd-sourced Earth Microbiome Project analyzes samples from around the world and the National Ecological Observatory Network collects samples from 81 freshwater and terrestrial sites across the U.S.

What's new: The Tara Pacific Expedition, between 2016 and 2018, collected nearly 5,400 samples from three types of coral, two fish species and plankton at each of 99 coral reefs. The researchers then sequenced a specific region of DNA in the microbes and found more than 500,000 unique sequences, a proxy for species in this study.

- When the researchers extrapolated the findings to the total number of fish and coral species in Pacific Ocean reefs, the total microbiome diversity rose to 2.8 million types of bacteria — within the current estimate of between 2.2 million and 4.3 million for the entire planet, they write in Nature Communications.

- The microbiomes in the different areas sampled were distinct, and plankton in the water had more diverse microbiomes than marine animals.

Yes, but: There is debate about how to define a true species of microbe. Unlike with plants and animals, the physiology and morphology of bacteria can't be easily separated and most can't be grown in a lab and analyzed.

- In the study, researchers analyzed their data with a widely used cutoff of 97% similarity in the genetic sequences to determine whether something is a species. But there are examples of microbes that have even higher genetic similarity but their genomes encode proteins with different functions so they could be considered different species, says Eloe-Fadrosh, who wasn't involved in the study, adding the reverse can also be true.

- Even if the same species aren't present, their functions — for example, carbon or nitrogen cycling — could be redundant. "That changes the picture of how you can actually estimate diversity," says Eloe-Fadrosh, who uses metagenomic sequencing of the total genetic content of microbes to estimate their diversity in permafrost, soil and other environments.

The intrigue: The immense diversity of the microbes on the reefs may offer "ecological insurance" for coral, fish and other inhabitants, Pierre Galand, a researcher at Sorbonne University in France and a co-author of the study, said in a press briefing.

- If some bacteria have similar functions, then one bacteria that doesn't survive due to environmental conditions could potentially be replaced by another, he told Axios in an email

- "The large diversity of the reef microbiome may thus be important because it could help mitigate environmental perturbations," he said. "It's a theory ... [and] will be the focus of future studies."

What's next: The researchers said they plan to look at how environmental factors affect the microbiome.

- "There's no direct link or correlation now between the decline in the coral reef and a change in the microbiome," said expedition leader Serge Planes of the University of Perpignan in France in the press briefing, adding that is "mainly because we know so little about the microbiome."

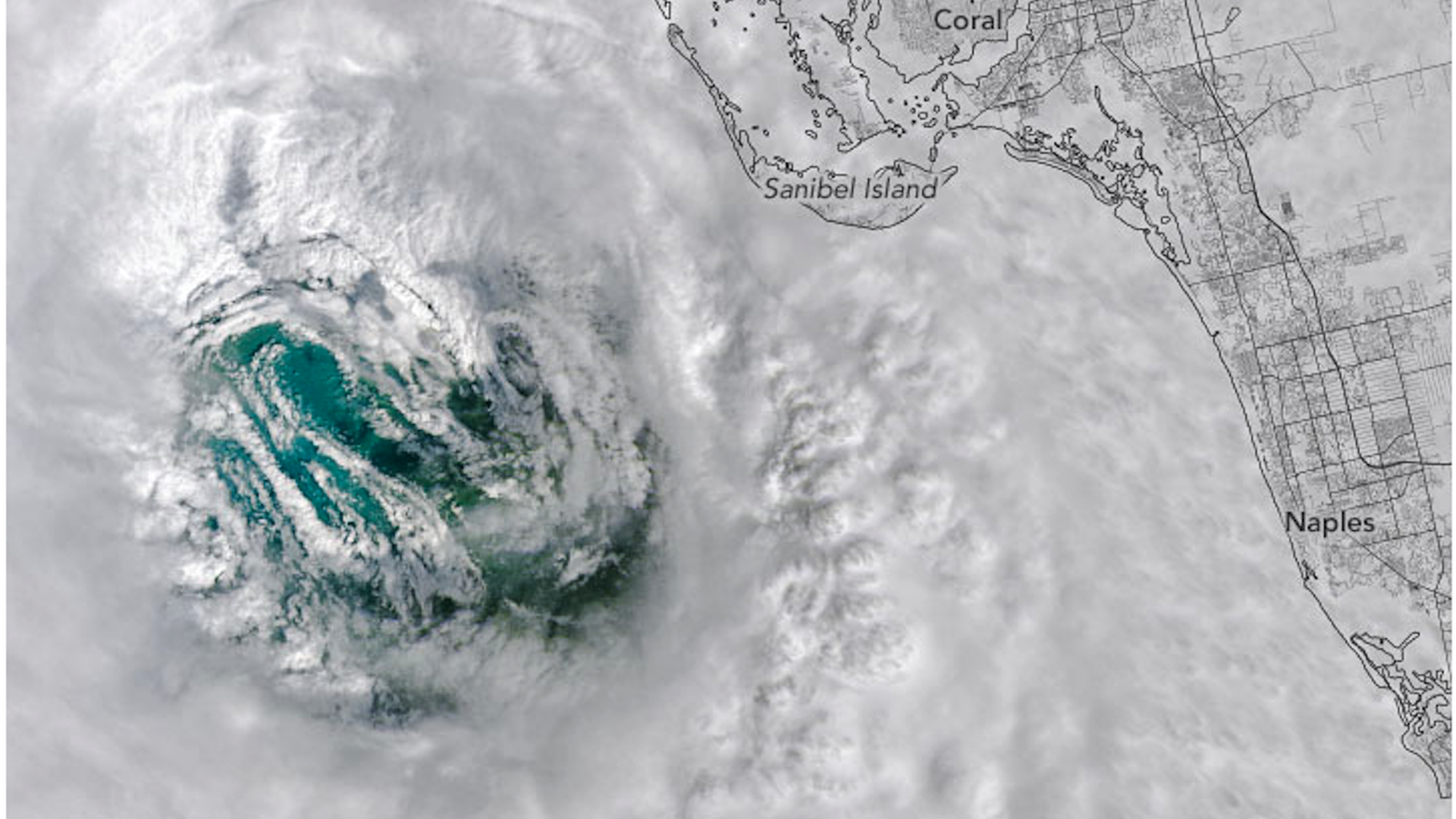

2. New airborne radar could revolutionize hurricane forecasting

Closeup of Hurricane Ian's eye seen from space as the storm struck Sanibel Island, Florida, on Sept. 18. Image: NASA

Next-generation radar technology capable of taking 3D slices of hurricanes and other storms is poised to move ahead, after years of fits and starts, Axios' Andrew Freedman reports.

Driving the news: The National Science Foundation announced $91.8 million in funding this morning — the first day of the Atlantic hurricane season — for the National Center for Atmospheric Research to design, build and test an airborne phased array radar (APAR).

- The technology consists of thousands of transmitters and receivers on horizontal plates mounted at different points on a plane.

- Together, they would scan storms in unprecedented detail, from storms' overall organization to the type, shape and direction of movement of droplets within the clouds.

Why it matters: Currently, NOAA’s aging hurricane research aircraft fly tail-mounted Doppler radars into the hearts of hurricanes. But the new APAR could yield significant insights into weather predictions and climate projections.

- For example, it could provide a far more detailed picture of the inner structure of a hurricane. The data can then be fed into computer models to warn of sudden intensity changes and track shifts.

- The NSF press release cites climate change’s “unprecedented threats” as a reason for the new funding.

Zoom in: The funding will be used for a radar-outfitted C-130 research aircraft, operated jointly by NSF and NCAR.

- The center's director, Everette Joseph, said the radar should be ready for use in 2028.

- In addition to the center's research radar, NOAA is planning to buy a new fleet of C-130 Hurricane Hunters, and outfit them with APAR units. It aims to have them flying in 2030.

3. Spotting more cosmic collisions

/2023/05/31/1685549669834.gif?w=1920)

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

The search for ripples in space and time sent out by extreme cosmic collisions is entering a new phase with more and faster detections, Axios' Miriam Kramer writes.

Why it matters: These ripples — called gravitational waves — carry information about crashes between dense objects like black holes and neutron stars that scientists use to test long-held theories about the universe.

What's happening: Two gravitational wave detectors — in Washington State and Louisiana — are now back online after three years of upgrades to improve their sensitivity.

- It's possible that once the detectors that make up the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) are at full strength, they will detect a gravitational wave signal every two or three days.

- Previous observations have netted between 90 and 100 detections since LIGO clocked its first gravitational wave in 2015, astronomer Chad Hanna of Penn State tells Axios, adding, "It's quite likely that we will add several hundred more."

- More observations mean more opportunities to see the rarest events in the universe, Hanna says.

How it works: LIGO makes use of a laser that sends a beam of light down the arms of the L-shaped instrument. That light bounces off the end of the arm and back to the middle, always arriving at precisely the predicted time.

- However, if a gravitational wave passes through Earth's part of space, it slightly bends the fabric of space-time, imperceptibly warping every piece of matter it passes through, including the detector. That creates a very slight change in the time that light reaches the middle of the detector.

- By having multiple detectors operating at once, scientists are able to more precisely track signals to the parts of space they originate from, Katerina Chatziioannou, physics professor at CalTech, tells Axios.

The intrigue: Astronomers think LIGO's improved sensitivity could allow them to more readily see light and other signals like radio waves emitted during crashes between two neutron stars and possibly other objects as well.

4. Worthy of your time

A scientific guide to clouds (Briley Lewis — Popular Science)

The human brain’s characteristic wrinkles help to drive how it works (Davide Castelvecchi — Nature)

Ian Hacking, eminent philosopher of science and much else, dies at 87 (Alex Williams — NYT, subscription)

5. Something wondrous

Europa. Image data: NASA/JPL-CalTech/SwRI/MSSS; Image processing: Kevin M. Gill CC BY 3.0

"We are creatures of constant awe, curious at beauty, at leaf and blossom, at grief and pleasure, sun and shadow," U.S. poet laureate Ada Limón writes in her new poem that will fly to Jupiter's moon Europa aboard NASA's Europa Clipper mission.

- "And it is not darkness that unites us, not the cold distance of space, but the offering of water, each drop of rain."

- The poem, unveiled at an event tonight at the Library of Congress, is going to be engraved in Limón's handwriting and affixed to the spacecraft, expected to launch in October 2024, Miriam writes.

The big picture: The Europa Clipper mission follows in the tradition of others — like NASA's Voyagers — that have sent pieces of art representing humanity into the cosmos.

- The poem uses water as a thread that binds Earth — and all of its humans — to Europa, a moon with an ocean beneath its icy shell.

For Limón, writing this poem was a very human endeavor.

- "The thing I think that makes me the most beautifully overwhelmed is the idea of all the humans that are going to read it," she tells Axios.

- The poem, called "In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa," is featured on a NASA webpage where people can sign up to send their names to Europa with the spacecraft.

- "I think to have it feel collective is really, really extraordinary to me, because it does feel like it's not my poem," Limón says. "It does feel like a collective poem. And as soon as I wrote it, it felt like oh, this belongs to Earth. This is our poem for Earth."

Between the lines: Sending this poem to Europa is an "evolution" of NASA's Golden Record, which is flying through space aboard the Voyager spacecraft, Robert Pappalardo, Europa Clipper project scientist, tells Axios.

- Those records contain sounds from Earth — including music, laughter and animal noises — as well as a map of where we are in the galaxy. They are now billions of miles away, flying through interstellar space.

- "This is an outgrowth in that we're not going to the stars," Pappalardo says. "There's no message to aliens here. This is purely a message to ourselves and a symbolic message to Europa."

Thanks to editor Laurin-Whitney Gottbrath, Miriam Kramer for contributing, Aïda Amer on the Axios Visuals team, and Jay Bennett for copy editing this edition.