Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

When you hear "youth sports," colorful images of orange slices and vivid memories of pizza parties might fill your head. Perhaps then your mind shifts to some of the recent trends: skyrocketing costs, participation declines, the rise of specialization and the world of pay-to-play leagues and mega-complexes.

The state of play: The professionalization of youth sports has created a world of private coaching and inter-state travel with families willing — and able — to spend as much as $20,000 per year on youth sports.

- Meanwhile, low-income families have been priced out, robbing their children of the opportunity to not only excel at a sport but also exercise regularly and make friends.

- The most optimistic projections for a return of youth sports are by late August, meaning most seasons and tournaments have been cancelled. The industry stands to lose billions and a landscape-altering reckoning awaits.

Why it matters: The same way kids don't go to school just to learn algebra or the periodic table, they don't play sports just to get better at kicking or hitting.

- Coaches are tasked with teaching teamwork, accountability and countless other life skills. But with youth sports on pause, so are those developmental opportunities.

By the numbers: According to a survey conducted by LeagueSide, which connects youth sports organizations with sponsors, 49% of parents believe their children will be less likely to participate in youth sports due to financial circumstances, which could leave nearly 20 million kids on the sidelines.

- Beyond that, 85% of parents listed sports as a key way for their kids to make friends, laying bare that this is about much more than missed practices.

The big picture: There's no returning to normal. The question is: what is the youth sports model that comes out of this?

- Does this crisis simply widen the gap between those who can afford to pay for travel teams and those who can't? Or will it lead to a hard reset that brings about fundamental change and makes youth sports more inclusive?

- These questions have implications not only for the health and well-being of children, but also for the professional leagues that rely on youth sports to forge future generations of players and fans.

The bottom line: COVID-19 has placed youth sports at a crossroads, and this forced hiatus gives us a chance to examine the state of industry and what it might look like when this crises wanes.

2. Where things stand

A youth sports coalition of local and national organizations are seeking $8.5 billion in federal aid through an extension of the CARES Act to help the industry survive the crisis and come out the other side intact.

- The state of play: 50% of youth sports organizers fear they won't have the financial resources to pay for facilities and staff, according to a survey conducted by LeagueApps, a youth sports management platform.

Driving the news: The bipartisan co-chairs of the Congressional Caucus on Youth Sports — Rep. Ron Kind (D-Wis.), Rep. Rodney Davis (R-Ill.), Rep. Marc Veasey (D-Texas), and Rep. Kelly Armstrong (R-N.D.) — sent a letter to Congress this weekend with signatures of support from 27 other U.S. representatives.

- "[M]any youth sports organizations have seen their entire revenue stream stop, particularly their membership fees and dues which are essential to program operations," the letter reads.

- "Furthermore, many youth sports programs, especially the non-profits, are particularly reliant on corporate and philanthropic giving. Much of that support often comes from local restaurants and other businesses who are no longer able to give and probably will not be for quite some time."

The other side: Tom Farrey, the executive director of the Aspen Institute's Sports & Society Program, tells me he doesn't think now is the right time to request federal aid and isn't confident the money would benefit those who need it most.

"Wrong ask, wrong time. My sources say Congress is focused on too many other problems at the moment. There's a time to make an ask, but we have to get this right and make sure any funding goes where it's needed in the coming months and years — to support affordable, high-quality community programs that can serve all kids."— Tom Farrey tells Axios

What to watch: Ready or not, America is gradually reopening. When and how youth sports join in will play out in the coming months, but since there's no youth sports ministry in this country, it will likely differ greatly from state-to-state.

3. The youth sports exodus

The average child today spends less than three years playing a sport and quits by age 11, according to a 2019 survey of sports parents conducted by the Aspen Institute and Utah State University.

- One might suspect this decline is the result of video games and other electronic distractions, but dig into the numbers and a more complex — and upsetting — story emerges.

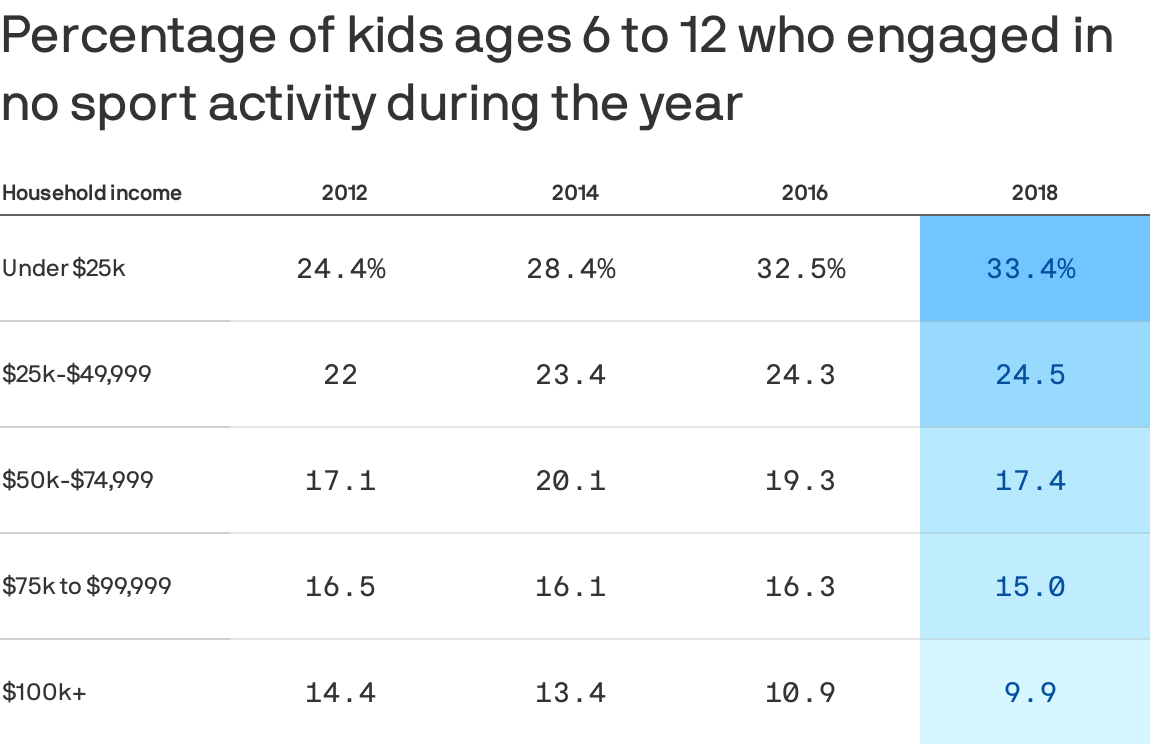

By the numbers: Only 38% of kids aged 6 to 12 played team sports on a regular basis in 2018, down from 45% in 2008, per the Sports & Fitness Industry Association.

- But among richer families, participation is actually rising. It's the poorer households where the numbers are trending way down.

The bottom line: Youth sports in America has become a story of the haves and the have-nots. In the wake of the coronavirus, where does it go from here?

4. The history of youth sports in America

Youth sports wasn't always big business. Tracking its evolution in America over the past 150+ years helps explain how we got here.

In 1852, Massachusetts became the first state to pass a compulsory education law, requiring children to attend school. By 1918, every state had followed suit.

- For context, think about the tales of Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn: Before school was mandatory, kids roamed free. That's not to say they were all searching for buried treasure, but the lack of structure gave way to adventure and mischief.

- With the advent of schooling, a child's day transformed into clearly delineated segments, leaving parents to decide how to fill their children's non-school "free" time.

- The first solution was to establish parks and playgrounds — safe, public spaces for kids to play. Then came organized sports, which offered more structure and taught life lessons that playground games simply couldn't.

"Sports were seen as important in teaching the 'American' values of cooperation, hard work, and respect for authority."— Hilary Levey Friedman, The Atlantic

In 1903, New York established the Public Schools Athletic League, pitting schools against each other for championships and bringing more competition to youth sports. By 1910, 17 other cities had formed similar organizations.

1920s–1940s: After three decades of growth, the Great Depression came along and decimated publicly-financed youth sports organizations, causing an unfortunate ripple effect.

- The good news was that pay-to-play organizations like Pop Warner and Little League Baseball sprung up to fill the void. The bad news was that this change priced poorer families out.

1940s–1960s: While pay-to-play leagues grew in popularity and engulfed the country, educators worried that emphasizing sports in elementary schools would create too much stratification between those with talent and those without.

- By the 1960s, that attitude had blossomed into a full-blown movement around self esteem, the results of which are still visible today in the fact that interscholastic sports tend not to begin until middle school.

1972: Up until now, all these organized sports had one thing in common — they catered mostly to boys. When Title IX passed in 1972, that changed in a big way.

- By the numbers: Before Title IX, one in every 27 girls played sports. By 2016, it was two in every five, according to the Women's Sports Foundation, and the number of girls playing high school sports was up 990%.

1970s-present: When Boomers began graduating from high school, colleges were flooded with record numbers of applications. Suddenly, it was no longer enough to simply be smart.

- Parents — whose philosophies and attitudes led to the shifting policies throughout this whole timeline — saw this as another competitive opportunity, with sports acting as the differentiator on their kids' résumés.

- It has since become the norm to use sports to land scholarships — or, for the very best players, chase stardom. This has created a new breed of specialized athlete, while simultaneously stripping local leagues of resources and pushing the less fortunate out of the picture.

5. The fear: A widening of the equity gap

As school-based sports and local parks and recreation departments fall victim to coronavirus-related budget cuts, and families suffer from the economic fallout, the fear is that the equity gap in youth sports will get even wider.

- Parents who can still afford the pay-to-play model will, of course, have their children playing. But more lower-income families than ever could be priced out, leading to further drops in participation.

- Despite increased demand for local sports programming post-COVID-19 (due to economic strain and also health concerns around travel), municipalities and other low-cost or free sports providers could struggle to meet the demand.

The bottom line: Contraction is coming to youth sports, and the reality is that the well-funded organizations that cater to the travel sports industry have a far better chance of surviving and thriving than the cash-strapped local organizations that serve all kids.

6. The hope: A hard reset

Many youth sports leaders who I spoke with agreed that one of the biggest positives to come out of this shutdown is the reemergence of "free play."

- Families are being active together, fathers and sons are playing catch for the first time in years, little girls are inventing new games to keep themselves entertained, kids are riding bikes and running more.

- In many ways, the past few months have been a return to the way kids played sports a generation or two ago (or how they do it in Norway today).

- This could ultimately help erase the notion that sports equal "organized play," and ultimately create a future where free play has a bigger role.

7. The rise of virtual training

With teams unable to practice, play games or meet in person, there has been a significant increase in virtual training and virtual team meetings.

- HomeCourt, which uses AI to track basketball skills and can turn a driveway shooting workout into a trove of data, has been one of Apple's most downloaded sports apps for the past two months (currently No. 4).

- Other examples: "Techne Futbol, a soccer-skills app created by a former [USWNT] player, saw 30 times more users than before the pandemic. Famer, an app that offers virtual coaching in numerous sports, doubled in usage almost every day during the first two weeks of the shutdown," per WashPost.

In addition to individual training, teams are also holding virtual meetings or "hangouts," which has thrust coaches into a new, important role.

"The role of a youth sports coach has evolved during this crisis. They're still reinforcing the life lessons that sports are designed to teach us, but it's been great to see so many providing that social and emotional support — checking in on their players, and establishing a better rapport with parents."— Chris Moore, Positive Coaching Alliance CEO, tells Axios

The big picture: The shutdown has forced youth sports organizations to embrace technology in new ways, and many have taken this time to digitize and improve their operations. A potential result: no more canceled practices.

"We surveyed hundreds of organizations and 68% said they've launched or plan to launch virtual programming. And they're all realizing 'Oh wow, this could be a permanent feature of how we add value.' If a practice is rained out in the future: 'Hey guys, let's meet virtually.'"— Jeremy Gould, LeagueApps CEO, tells Axios