Axios Science

May 06, 2021

Welcome to Axios Science. This week's newsletter — about coronavirus variants, quantum entanglement and more — is 1,681 words, about a 6-minute read.

- Send feedback and ideas to me at [email protected]. You can reach Eileen Drage O'Reilly at [email protected].

- Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up here.

1 big thing: The vaccine race to avoid a "monster" COVID variant

Illustration: Rae Cook/Axios

Slow global COVID-19 vaccination rates are raising concerns that worse variants of the coronavirus could be percolating, ready to rip into the world before herd immunity can diminish their impact, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly writes.

Why it matters: The U.S. aims to at least partially vaccinate 70% of adults by July 4, which is expected to accelerate the current drop of new infections here. But, variants are the wild card, and in a global pandemic where only about 8% of all people have received one dose, the virus will continue mutating unabated.

How it works: Viruses mutate and selective pressure can favor those mutations that transmit easier in the population or that better escape human's innate immunity, says Sarah Cobey, associate professor of ecology and evolution at the University of Chicago.

- "We're seeing both right now," she says.

Where it stands: The CDC currently says there are five variants of concern and eight variants of interest in the United States.

- Two variants of concern — New York and California — may be dropping off and "on their way to extinction," says Eric Topol, founder and director of Scripps Research Translational Institute.

- Three variants raise more worries — those originally discovered in the U.K. (B.1.1.7), Brazil (P.1) and South Africa (B.1.351) — partly because "they accrued many mutations, over a dozen, almost instantaneously," says Josh Schiffer, an infectious disease expert at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

- These three variants show varying levels of increased infectiousness, particularly B.1.1.7. Plus, P.1 and B.1.351 may be more able to evade the immune system or vaccination properties, Schiffer adds, although more data is needed.

- The CDC is closely watching several versions of B.1.617, a variant first detected in India that may be linked to the surge in cases there now.

What to watch: "Rapid vaccination is critically important. ... Even with partial protection you can achieve higher degrees of herd immunity," Schiffer says. "When I think of herd immunity, I don't think of it as an all-or-none phenomenon. I think of it as a dimmer switch."

- "The factories for generating new variants are areas that are getting hit very hard. If there is a new variant that's terrible — that ruins 2022 and brings us back to very dark times — it's almost a guarantee that it's percolating in an area of the world that's getting hit very hard now," Schiffer says.

- "The one thing that could happen, but hasn't happened yet, is to have a superspreader variant like B.1.1.7 with very powerful immune evasion. ... Will we see that? I don't know. Hopefully we'll never see that monster," Topol says.

Yes, but: The U.S. appears to be experiencing a drop in vaccination demand, despite the spread of variants.

- A new study in The New England Journal of Medicine shows the importance of people getting their second dose in fighting off the variants — but some Americans are not.

- And foreign nations are struggling to get access to vaccines, with the U.S. only now starting the process to fill in the vaccine diplomacy void.

The bottom line: "It's just next to impossible to predict what's going to happen next," Schiffer says.

- "I think the likelihood that we would have a variant that emerges that is worse than the ones we're dealing with now is much higher if you have a higher circulating number of infections," such as what's happening in Latin America, India and Asia.

Go deeper: Check out our live Coronavirus Variant Tracker.

2. Catch up quick on COVID-19

"Coronavirus infections in the U.S. are now at their lowest levels in seven months, thanks to the vaccines," Axios' Sam Baker and Andrew Witherspoon report.

The Biden administration said this week it will support waiving COVID-19 vaccine patents in an effort to try to increase the global supply of shots.

Pfizer expects to seek emergency use authorization for its COVID-19 vaccine in people ages 2-11 in September.

Results from a late-stage clinical trial of a third RNA vaccine — developed by CureVac in Germany — are expected this month, Carl Zimmer reports for the NYT. Unlike the two RNA vaccines from Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech, this one can be stored refrigerated and could be more easily distributed around the world.

3. Quantum weirdness goes big

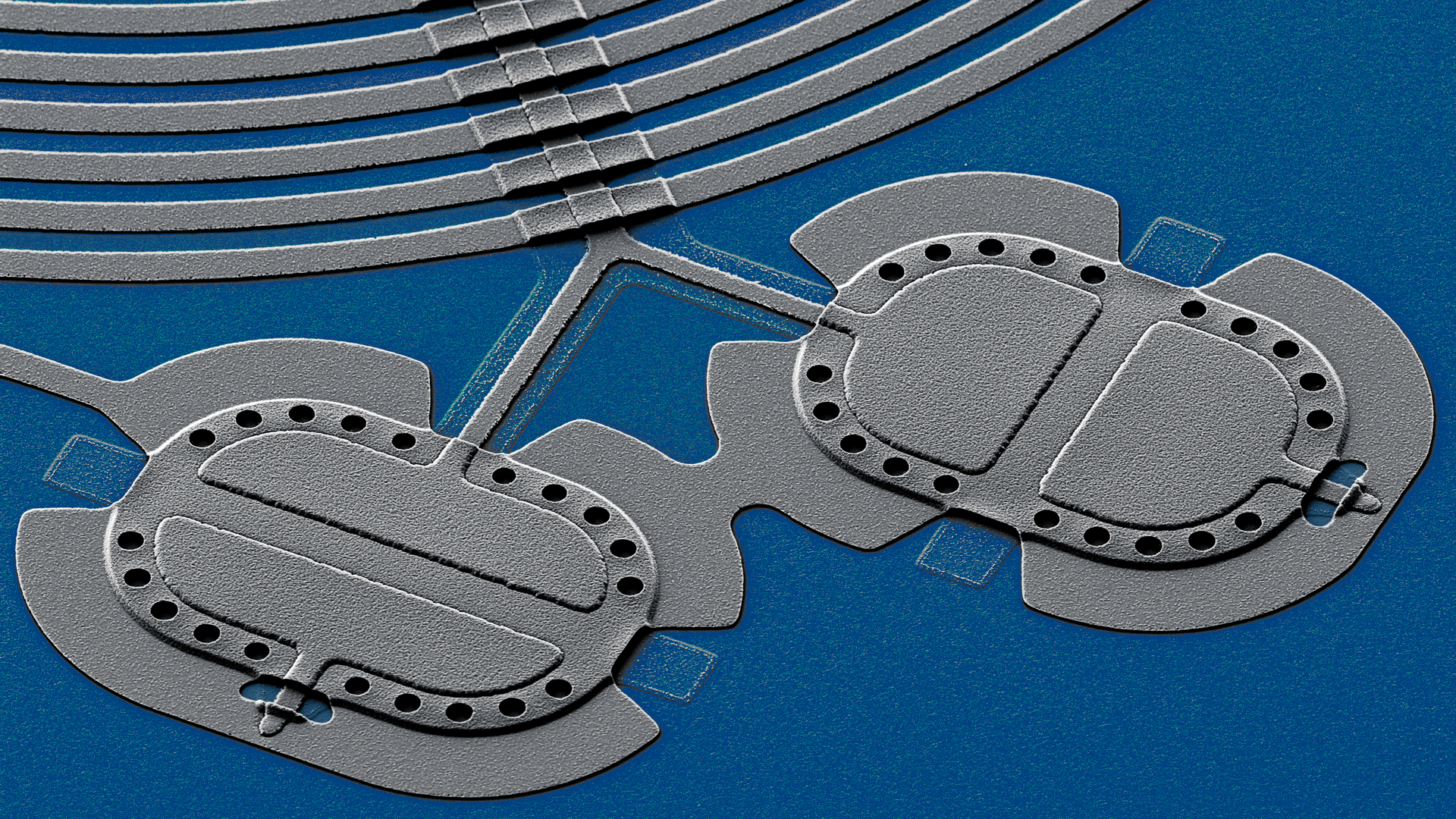

Scanning electron micrograph of quantum drum device. Image: John Teufel/NIST

The quantum phenomenon of entanglement can be created and, crucially, measured directly in objects made up of roughly a trillion atoms, scientists report in a pair of papers published today.

Why it matters: Quantum mechanics are, in theory, at play in the visible world, but the strange effects are masked and difficult to observe when more than a few atoms are involved.

- The new research demonstrates "how far into the macroscopic realm experiments can push quantum phenomena,” Hoi-Kwan Lau of Simon Fraser University and Aashish Clerk of the University of Chicago, who weren't involved in the research, wrote in an accompanying piece.

- The techniques in the papers could be used as a basis for creating gates for quantum computation or for nodes to store and transmit quantum information between disparate quantum technologies, they write.

How it works: Atoms can exist in an "entangled" state, where if the position or velocity of one atom is changed, the other atom in the pair will change too — even if they are separated by a long distance. Entanglement underpins the computational advantage quantum computers have over classical ones.

What they did: The experiments in both new studies use two tiny aluminum membranes, or drums, about the diameter of a human hair — massive on the quantum scale.

- In one set of experiments, researchers placed drums about 100 microns apart — but isolated from one another — in a circuit at nearly absolute zero. They then used microwave light pulses to vibrate the drums in sync and entangle their atoms. They could then directly measure their motion, a rise and fall over the extraordinarily small distance of one-quadrillionth of a meter.

- "To verify the entanglement, we measure the vibrations of two drums over and over again and show that the motion is not independent, but is so correlated that it cannot be explained by classical physics," says John Teufel of the National Institute of Standards and Technology and an author of the paper.

- In a second paper, led by researchers in Finland, different microwave frequencies were used to create a long-lasting entanglement of the drums and measure the entangled state without destroying it, an effect known as "back action."

"These entanglement demonstrations are at the forefront of where these massive quantum systems are," Teufel says of both papers.

4. World risks runaway Antarctic ice melt if Paris targets not met

Mountain peaks in the Antarctic Peninsula region on Nov. 4, 2017. Photo: Mario Tama/Getty Images

Two major new studies on sea level rise both show the benefits of limiting global warming to the Paris Agreement temperature targets, Axios' Andrew Freedman reports.

Why it matters: The papers, published in Nature, find that limiting warming to 1.5° C or 2° C above preindustrial levels brings the greatest chance of avoiding tipping points in the Antarctic Ice Sheet.

- Both papers agree if warming is limited to the targets of "well below" 2°C (3.6°F) — a big "if" given recent emissions trends — sea level rise from Antarctica will proceed at about the same pace it is today through 2100.

- By that time, the continent will have contributed about 9 centimeters to global sea level rise.

- But if 3°C of warming or higher occurs, sea level rise could begin to accelerate irreversibly as soon as 2060, one study shows, and spike to 15 to 34 centimeters, or 13.4 inches by 2100.

What they did: Climate scientists Rob DeConto of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and his colleagues used hundreds of simulations from computer models of ice sheet behavior to recreate historical and recent ice loss and sea level rise, and make future projections.

- Researchers tossed out projections from simulations that were inconsistent with observations and historical data. They also incorporated 16 years of detailed satellite imagery to help make the modeling as precise as possible.

- They limited the ice cliff instability to observations from glaciers in Greenland, but DeConto noted that it remains a "wild card" that could significantly speed up Antarctic ice loss.

- The other study, led by Tamsin Edwards of Kings College in the U.K., looked at land ice loss worldwide and found limiting global warming to 1.5°C would cut in half the land ice contribution to sea level rise when compared to the current pace.

Yes, but: The study Edwards led does not include the ice shelf or cliff instabilities that could drastically increase Antarctic melt.

- It warns that ice loss from that continent could be up to five times higher, which would boost the land ice loss contribution to sea level rise from between 13 to 25 centimeters to up to a half a meter by 2100.

5. Worthy of your time

Finding the mother tree (Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee — Emergence)

Psychedelic drug passes a big test for PTSD treatment (Rachel Nuwer — NYT)

The oldest burial in Africa (The Economist)

Hubble watches a planet grow (Miriam Kramer — Axios)

6. Something wondrous

The space between sand and sediment at the bottom of the sea is home to tiny animals called loriciferans. This week researchers describe three new species of the animals found off the coast of France.

The big picture: These minute animals are part of a lesser known group of fauna in the oceans whose role in the ecosystem is largely understudied.

Details: The animals in the phylum loricifera are typically less than half a millimeter long. Smaller than megafauna like crustaceans and clams but larger than microscopic zooplankton, they're part of what's known as meiofauna.

- An exoskeleton of plates and folds called the lorica protects the animal's abdomen (and gives loriciferans their name).

- Loriciferans can move backward and jump forward, with their snout extruding, a strange movement that may be for foraging, says Ricardo C. Neves of the University of Copenhagen and an author of the new study.

"They are amazing and different from anything else," he says.

- The research published this week in the journal PLOS One brings the tally of described loricifera species to 43. The species, one of which has distinct features and is part of a new genus, were determined using specimens the researchers began collecting in 1985.

- A decade ago, researchers found three loricifera species living in sediment deep in the Mediterranean Sea — without oxygen. Those species appear to lack mitochondria, which use oxygen to generate chemical energy for cells to function, and to have found another way to survive extreme conditions.

What's next: Neves says they want to sample more specimens and confirm the species don't have mitochondria — and what kind of organelles they do have, while better understanding their evolutionary relationship to other small animals, including tardigrades and arthropods, and their role in the ocean ecosystem.

Editor's note: The top story was updated to clarify how viruses mutate.

Sign up for Axios Science

Gather the facts on the latest scientific advances