Axios Science

June 13, 2019

Thanks for subscribing to Axios Science. Today's edition is 1,607 words, for about a 6-minute read.

I appreciate any tips, scoops and feedback — simply reply to this email or send me a message at [email protected]. Please consider inviting your friends, family and colleagues to sign up.

🚨Over the past few weeks, we've included word count and time to read at the top of each of our newsletters. Now, we want to hear from you — love it or hate it? Click here for love and here for hate. For the curious ones out there, we'll share the results next week.🚨

1 big thing: Ebola spreads, as world awakens

The long-simmering Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo entered a new and more ominous phase this week, with the cross-border spread of a handful of cases into western Uganda.

Why it matters: The cross-border spread puts more pressure on the World Health Organization to declare the nearly yearlong outbreak a public health emergency, which it has proven reluctant to do. A committee will meet Friday to determine whether to take that step.

But, but, but: The international spread of Ebola was expected by health experts given the proximity of the outbreak areas in the DRC to the heavily trafficked border with Uganda.

- Health authorities in Uganda had been vaccinating health workers in anticipation of seeing cases.

- The overall trajectory of the outbreak remains unchanged, as health workers have been unable to break through community distrust and a violent insurgency inside the DRC.

- The high percentage of cases that are community cases, ones in which health workers were not aware of infected people or the individuals they have come in contact with, is especially concerning.

Details: This Ebola outbreak is already the second largest on record, and even the deployment of a successful vaccine has proven insufficient at arresting its spread. A key reason for this is the challenging security environment in which responders are operating.

- Health workers have been attacked and killed, and levels of community mistrust remain high in affected areas.

- “Insecurity and community mistrust are a huge barrier, and we don’t have ready-made answers for dealing with either of those,” says Stephen Morrison, director of the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Health workers in the DRC and Uganda are conducting ring vaccination campaigns using a vaccine supplied by Merck known as the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine.

- But the vaccine is not sufficient for preventing all new cases and fatalities with so many community cases.

- “The vaccine is not a silver bullet for this outbreak,” says Morrison.

The impact: Given the continued increase in cases in the DRC and the potential for additional spread into neighboring countries, health officials have expressed concern that the vaccine supply may run out in the next few months.

- In May, a WHO advisory group recommended that the DRC offer lower doses of vaccines and to consider using other experimental vaccines to stretch supplies.

What we’re watching: Unlike the 2014–2016 West Africa epidemic, this one has skirted below the radar of world leaders. The appointment of a high-level UN coordinator with extensive security experience has raised hopes of a more robust response.

- So far, the WHO has taken the lead in responding, sending hundreds of personnel to the region.

- The CDC has just 15 experts in the DRC, but the security situation has kept them confined to cities away from the outbreak zones, an agency spokesman tells Axios.

- Morrison and Jennifer Nuzzo, a senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, say the U.S. and other nations need to reassess their contributions to stopping this outbreak.

The bottom line: On its present course, Morrison thinks the outbreak could persist for another 1–2 years. The longer it lasts, the greater the chance it has to reach major population centers.

Go deeper: Axios' complete Ebola outbreak coverage

2. The details in Saturn’s rings

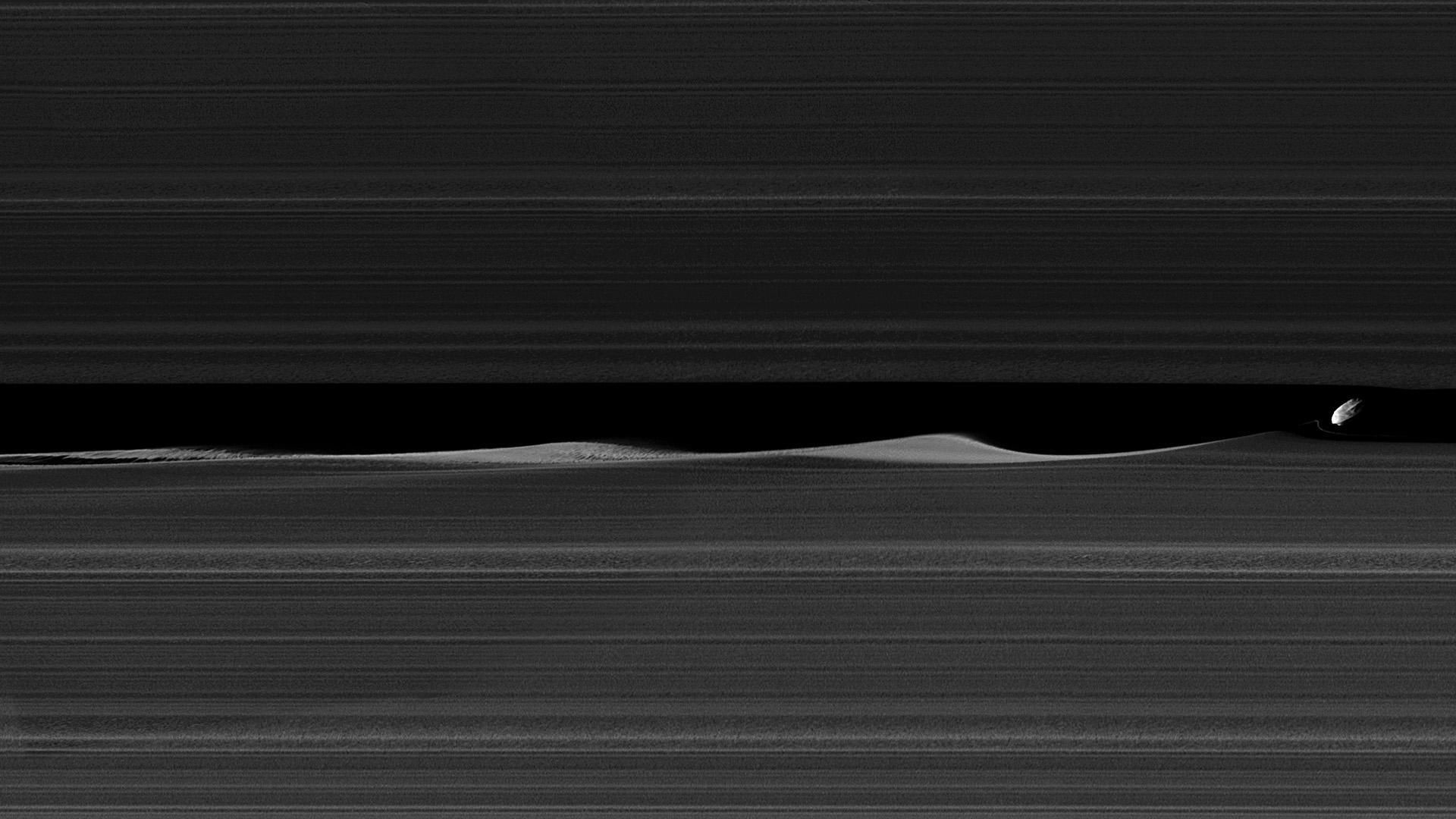

Saturn's moon Daphnis as viewed through the planet's rings by the Cassini spacecraft. NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

New details of Saturn’s distinctive rings were revealed, using data from NASA's Cassini mission, Axios' Miriam Kramer reports. The new data was published in the journal Science this week.

Why it matters: The system of rings and moons around Saturn provides scientists a glimpse into the broader machinations of lunar and planetary formation in our solar system and beyond.

What they found: Various parts of Saturn's rings — which are largely made up of ice and dust — appear to have different textures, according to the new study.

- Those textures — smooth, clumpy or streaky — can tell us about how these rings have evolved over time.

- For example, lead author Matt Tiscareno and his team found a series of streaks in Saturn’s F ring that appear to have been formed when some material orbiting Saturn slammed into the ring.

- The ring particles are also affected by small moons whose orbits bring them within or near the rings themselves. Those moons have a gravitational influence on the rings, changing their structures.

Context: Saturn’s rings are thought to be younger than the planet itself and may have formed when a moon was ripped apart in orbit around the planet.

- The rings also won’t be around forever. It’s even possible that other planets in the solar system like Jupiter and Neptune had huge ring systems at one point in the past.

“[R]ing systems are best seen as temporary churning debris fields that are being swallowed up by their parent planets, rather than some stable, stationary feature.”— James O’Donoghue, planetary scientist at JAXA, tells Axios via email

3. Researchers look at "Jumping genes" in CRISPR therapy

Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios

Two prominent teams of scientists recently announced that transposons — or "jumping genes" — can improve the precision of CRISPR gene editing, Axios' Eileen Drage O'Reilly reports.

Why it matters: While this research is still in the early stages, as both teams tested their techniques on bacterial cells, experts say the technique could allow edited genes to be more precisely inserted into genomes, possibly addressing concerns with current CRISPR systems that can lead to off-target editing and random deletions or even cancer.

Background: Transposons randomly jump from one site to the other, inserting genetic information as they go, using enzymes called transposases.

- CRISPR tools currently use enzymes like Cas9 and Cas13 to cut and delete a portion of the genetic code, counting on the cell to use its repair function to glue the cut strands back together. That process sometimes introduces its own problems.

- By combining the CRISPR tool with these transposons, which have the ability to easily introduce a large number of genes into cells, researchers hope to merge the best of both worlds, says Ilya Finkelstein, assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin who was not part of either study.

Details: Both studies essentially combine CRISPR with different transposons and, in the process, unveil details about how natural CRISPR systems have evolved and why there are a diverse number of systems.

Go deeper: Read the rest of Eileen's story

4. Arctic melt goes into overdrive

Earlier this year, we saw the unprecedented disappearance of sea ice from the Bering Sea during a time of year when it should be gaining ice. This trend toward plummeting sea ice in the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic continues, this time centered in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas.

Why it matters: Sea ice loss is disrupting the balance of heat in the Northern Hemisphere, and it is reverberating throughout ecosystems, causing everything from plankton blooms near the Arctic Ocean surface to mass haul-outs of walruses in Russia and Alaska. It may also be disrupting weather patterns across the Northern Hemisphere.

The big picture: Across the entire Arctic, sea ice extent is at a record low for this point in the year, and depending on weather conditions during the summer, it's possible that 2019 could set a new record low ice extent.

- The all-time record low sea ice extent was set in 2012, although subsequent years have nearly beaten that mark.

- So far, weather conditions have favored an early start to the Greenland ice melt season, too, and ice melt there, unlike disappearing sea ice, contributes to global sea level rise.

- The Arctic is warming at more than twice the rate of the rest of the world.

What they're saying: "At the moment, you can essentially sail uninterrupted from the North Pacific to the Canadian Arctic," says Zack Labe, a climate scientist and Ph.D. candidate at the University of California, Irvine.

"The Arctic is a regulator of Northern Hemisphere climate, and while the ice that is melting now isn't going to affect whether you get a thunderstorm tomorrow, in the long term, these are going to have profound effects on your weather and climate down the road that you will have to take action on, like it or not," says Rick Thoman of the University of Alaska at Fairbanks.

5. Axios stories worth reading

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

Child dies as Ebola outbreak spreads from the Congo to Uganda

NASA's murky commercial space future (Miriam Kramer)

"Dead zone" the size of Massachusetts predicted in Gulf of Mexico (Ursula Perano)

Big Tech's timid deepfake defense (Kaveh Waddell)

6. What we're reading elsewhere

How dengue, a deadly mosquito-borne disease, could spread in a warming world (Kendra Pierre-Louis and Nadja Popovich, New York Times)

Climate change is not causing wars yet (Nick Carne, Cosmos)

Where whales and plastic meet (Erica Cirino, Hakai Magazine)

Adrift in the Arctic (Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post)

Whole-body PET scanner produces 3D images in seconds (Sara Reardon, Nature News)

7. Something wondrous: An asteroid on the Moon

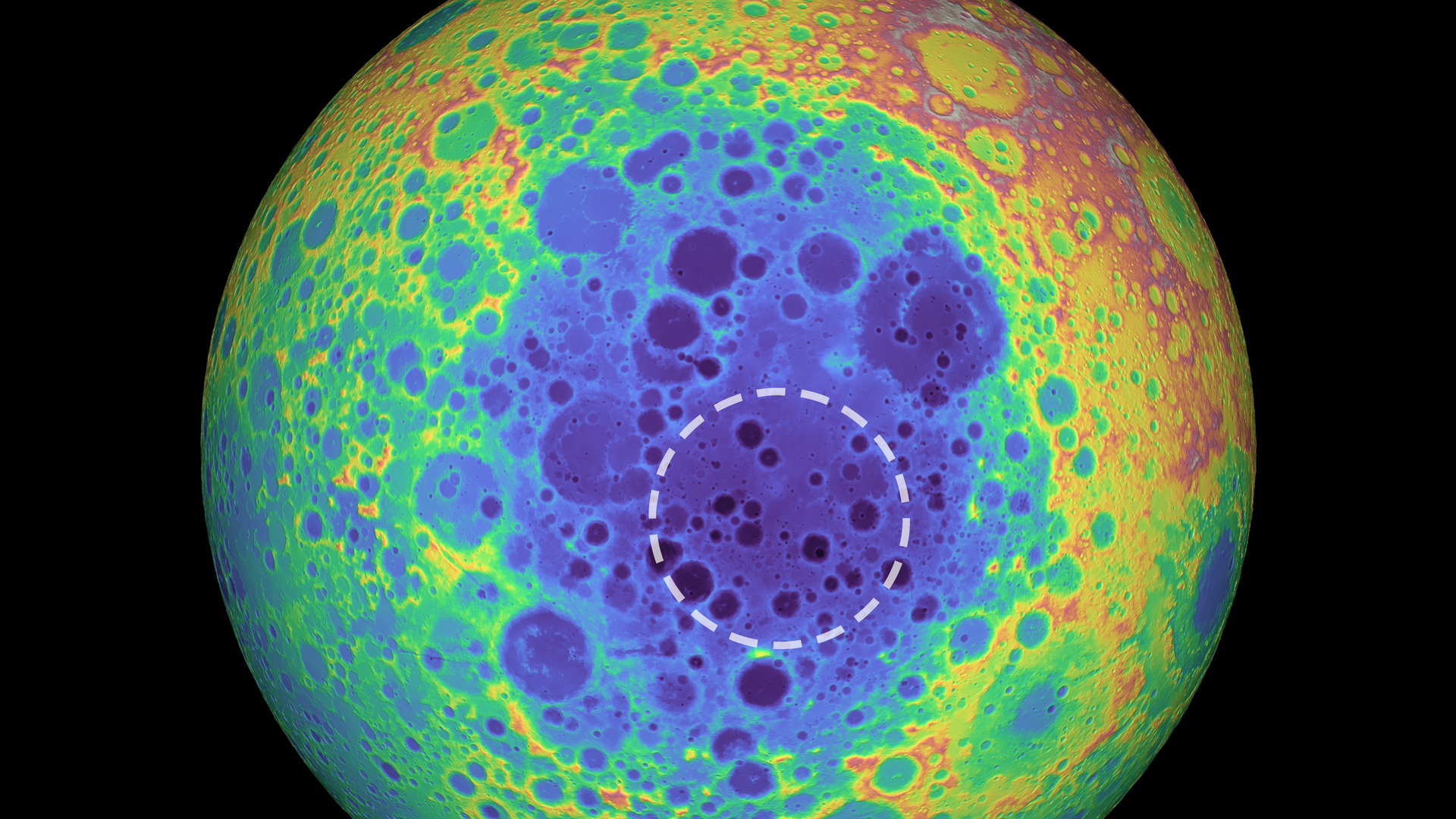

The topography of the far side of the Moon. The warmer colors indicate high areas, and the bluer colors indicate low regions. Dashed circle shows location of the mass anomaly. Image: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center/University of Arizona

A mass of metal from an asteroid may lurk under a 1,200-mile-wide crater on the far side of the Moon, Miriam reports.

The big picture: A study published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters suggests that some of the material from the asteroid that created the Moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin billions of years ago actually got stuck just under the crater, effectively weighing the floor of the basin down.

- “One of the explanations of this extra mass is that the metal from the asteroid that formed this crater is still embedded in the Moon’s mantle,” Peter James, lead author of the study, said in a statement.

Details: Scientists found evidence of the possible asteroid pieces using data from NASA’s GRAIL mission, tasked with creating a gravitational map of the Moon to help scientists on Earth learn more about its structure.

- Whatever’s buried beneath the crater is actually dragging its floor down by about half a mile, according to James.

- A computer simulation used by the research team showed that an iron-nickel asteroid core could get caught in the Moon’s mantle just below the crater’s floor during an impact.

But, but, but: It’s also possible that something else could cause the unexpected GRAIL readings around the basin. The material could also be from dense material thought to be the result of the Moon’s magma ocean solidifying, for example.

Thanks so much for reading!

Sign up for Axios Science

Gather the facts on the latest scientific advances