May 17, 2024

Good morning, and happy Friday! Thanks again to all of you who have been hitting reply.

- You've sent a lot of interesting thoughts and ideas — many of which I hope to touch on in future newsletters, so keep 'em coming!

Today's word count is 1,206, or a 4.5-minute read.

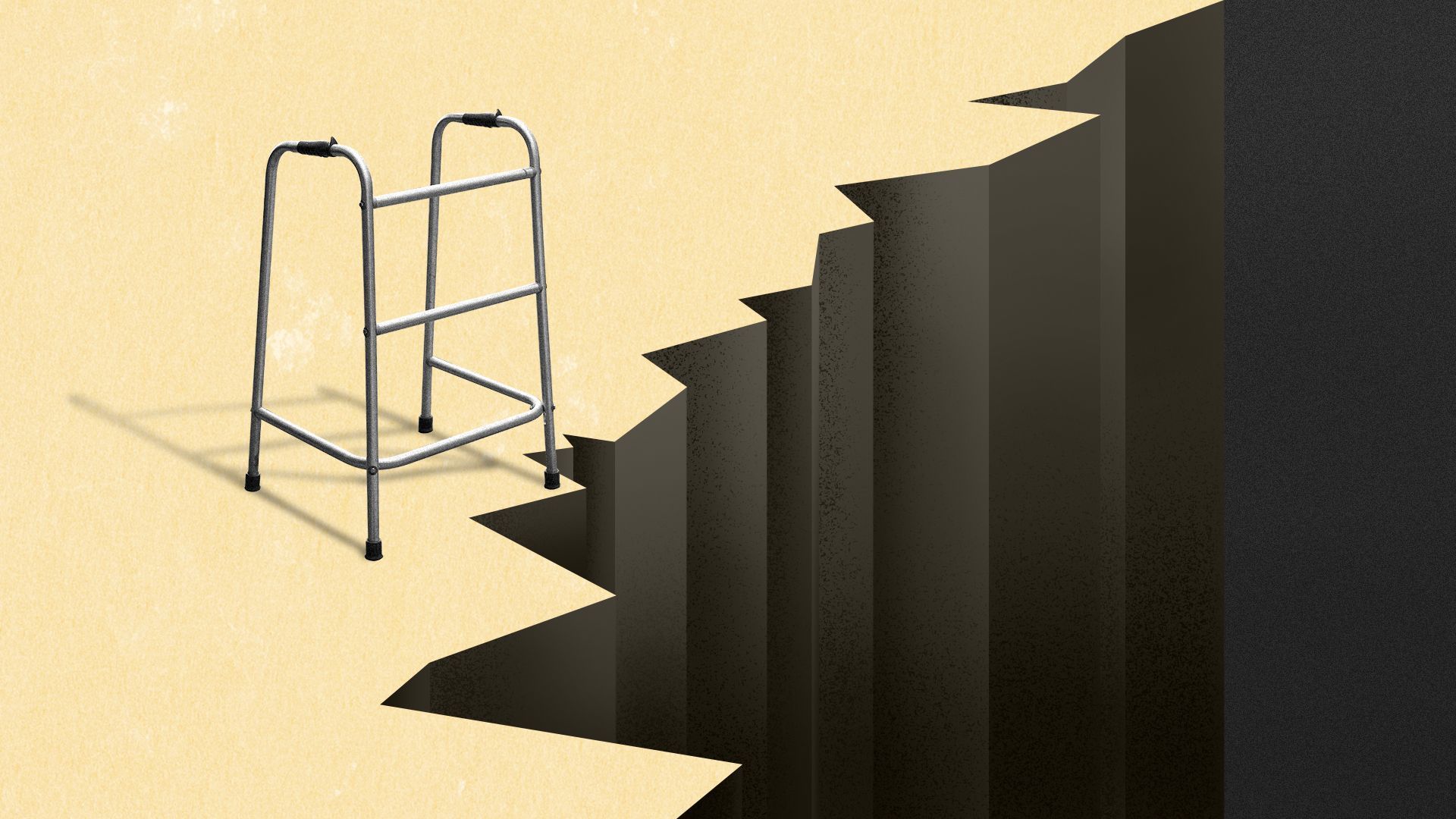

1 big thing: Hurtling toward the gray trap

Illustration: Lindsey Bailey/Axios

America is rapidly getting older — we knew this was coming. But we're now at the brink of that demographic shift's major consequences, and we're still completely unprepared.

Why it matters: It's not just that seniors are an increasing share of the population, which is a huge challenge in itself. The seniors of the future may also require care for longer, and aging inequalities are becoming more stark.

The big picture: Americans 65 and older will make up more than 20% of the population by 2030, according to Census Bureau projections, up from 17% in 2022. By 2050, they're projected to make up 23%.

- One of the most obvious impacts of the aging population is on the federal budget, as spending on health programs — namely Medicare — is expected to swell.

- But the change will be felt economywide: A smaller share of the population will be working age and, without drastic course correction, more may drop out of the labor force for caregiving responsibilities.

Between the lines: The economic effects won't be as drastic if seniors stay healthy longer and, as a result, work later into life. Not only would they use less health care overall, but they'd also continue to contribute to the economy.

- But things don't seem to be trending that way.

- "There's always been in the background an assumption that with increasing technical capacity in health care, that the older generation would be healthier than the preceding older generation," said John Rowe, a professor of health policy and aging at Columbia University.

- "What's becoming clear is that that optimistic scenario may not be playing out, and for whatever reason, older people in the next generation may enter late life more disabled than their previous counterparts," he said.

The U.S. is also woefully underprepared for the burden that aging seniors are expected to place on the health care system — particularly in terms of workforce demands — and support systems, whether formal or informal.

- There are already health care worker shortages, which worsened during the pandemic and are particularly acute in long-term care.

- "As we start thinking about these broader trends in aging and how we deal with it, there are a lot of things that aren't structured or ready for the growing demand," said Tim Lash, president of the West Health Institute, which is dedicated to improving aging. "In health care in particular, it's a dark spot."

- "Addressing it isn't just more bodies. Addressing it is fundamentally shifting what we're doing," he added.

The consequences of being unprepared for this gray tsunami are predictable but dire.

- Beyond the caregiving strain placed on family members, aging would likely become an even more deeply unequal experience.

- "People with resources and money and the best insurance will be able to get care, and as usual, the people without won't," Rowe said. "We're going to end up with a two-tier health system for older persons. And we don't want that."

The bottom line: The health of tomorrow's seniors will be shaped by how healthy they are now.

- There are signs that Americans now in their 40s and 50s will be even less healthy than today's seniors when they hit retirement age, and among this group there are widening disparities that will likely keep growing.

- "People don't get to 65 naive, as if they are now going to experience healthy aging or unhealthy aging," said Lisa Berkman, director of the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies.

- "If we want to think about healthy aging in America 10 or 20 years from now … we need to totally focus on the people who will be in those cohorts."

2. Sicker for longer

Americans are living longer, but an increasing portion of their lifespan is spent in poor health — and that gap is expected to widen, according to data released yesterday by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

- Even small increases in the gap, multiplied by millions of seniors, add up to a lot more demand for expensive health care or labor-intensive support.

The big picture: The U.S. gap between life expectancy and healthy life expectancy — or essentially a person's disability-free lifespan — is among the widest in the world, and projected to remain so through 2050.

- It's well-known that the U.S. performs poorly against similarly wealthy countries when looking at life expectancy alone, but this data suggests Americans are also outliers in terms of how much of their life is spent in poor health.

By the numbers: Americans born in 2023 can expect to live until age 79, and live in good health until age 66.

- That gap was smaller — only 10.8 years — in 1990.

- By 2050, U.S. life expectancy is expected to grow to just over 80, while healthy life expectancy will bump up to to 67 — a gap of 13.4 years.

Between the lines: This big and growing gap is expensive, as sick people require more resources.

- And comparing America with the rest of the world makes it clear that there are alternative ways for societies to age.

- "It's not like our genetics have made us more vulnerable suddenly. It's something in the environment is toxic," said Harvard's Berkman.

- "It's absolutely a miserable situation," she added. "You have to say, what are we doing that's driving this when other countries aren't going this way?"

3. Targeting aging itself

/2024/05/15/1715817561257.gif?w=1920)

Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios

Most of the world's leading causes of death are age-related. Instead of tackling diseases like cancer or diabetes to increase longevity, some researchers are attempting to find ways to slow or reverse the biological aging process itself.

Why it matters: If successful, an anti-aging therapy could help people live not only longer lives, but healthier ones, especially toward the end. And that would go a long way toward solving everything discussed above.

The big picture: "The distinction here is we're looking for approaches that are going to reduce the risk of all the major chronic diseases by targeting shared root causes," said Alexander Fleming, executive chairman of consultancy Kinexum and a former FDA official who oversaw approvals of drugs for diabetes and other metabolic diseases.

- "We are interested in actually intervening much earlier — in people your age and younger — to reduce your risk of getting these diseases." (I am 31, for the record.)

Where it stands: Researchers are evaluating the potential of existing drugs to slow or reverse aging, and clinical trials are underway to test such therapies on dogs.

Between the lines: Treating aging is one thing; preventing it is another — and from a practical standpoint, a much more challenging goal.

- While the holy grail would be to find a pill that young adults can start taking to prevent aging before it even begins, that would require proving the therapy is safe enough to justify perfectly healthy people taking it.

- "It's tough to fool Mother Nature," Fleming said. "You get one benefit but you may cause a problem at the same time."

4. One for the road

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and me yesterday morning. Photo: Bryan Dozier on behalf of Axios

If you missed our event yesterday on the youth mental health crisis ... don't miss the next one!

- It was a great conversation about a sobering topic, and hopefully only the first of many to come.

- Thanks again to Dr. Murthy, who we hope will also make a future appearance in this newsletter!

Thanks to Nicholas Johnston and Jason Millman for editing and Matt Piper for copy editing.