July 15, 2019

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here. (Smart Brevity count: 1,253 words / <5 minutes.)

Situational awareness:

- The number of U.S. retailers closing this year could rise to more than 12,000 by year-end, setting a new record. (CNBC)

- A proposal to ban big tech companies from acting as financial institutions or issuing digital currencies has been circulated by top Democrats on the House Financial Services Committee. (Reuters)

- Licenses for companies to re-start new sales to Chinese telecom Huawei may be approved by the U.S. in as few as 2 weeks. (Reuters)

- China's GDP growth slowed to 6.2% in the second quarter, the weakest pace since quarterly data began in 1992, but in line with Chinese government projections, while factory output and retail sales growth beat estimates. (Bloomberg)

1 big thing: The global debt binge begins anew

Reproduced from Institute of International Finance; Chart: Axios Visuals

The world's debt rose by $3 trillion in the first quarter of 2019 — an almost unprecedented borrowing binge that brought total global debt to $246.5 trillion.

Why it matters: High levels of debt put countries in a vulnerable position in the event of a downturn and could endanger the world's economic recovery, said economists from the Institute of International Finance, which released the study today.

What's happening: Countries had been reducing their debt burdens since the beginning of 2018, when global debt reached its highest level on record, $248 trillion. But Q1's major uptick brought it to nearly 320% of the world's GDP, also near the all-time high, according to IIF's data.

- Lower global interest rates and increased government spending are fueling the trend.

- Total U.S. debt rose to a new all-time high of more than $69 trillion — led by federal government debt, which is now over 101% of GDP.

- The U.S. corporate sector is also issuing more debt, boosted by an increase in bank lending, IIF noted.

What they're saying: "The 2018 slowdown in debt accumulation is looking more blip than trend," Emre Tiftik, IIF's deputy director of global policy initiatives, said in the report, released today.

- "Helped by the substantial easing in financial conditions, borrowers took on debt in Q1 2019 at the fastest pace in over a year."

- Further, Tiftik added, there's growing concern that central banks easing policy around the globe will prompt countries to issue more debt. "For some vulnerable low-income countries, debt sustainability is already at risk," he said.

Background: The Fed is expected to lower U.S. overnight interest rates at its policy meeting this month, following rate cuts from the central banks of Australia, India and New Zealand as well as multiple emerging market countries this year.

- Market analysts are expecting the world's largest monetary authorities to embark on a coordinated effort to loosen policy, as the ECB and BOJ also are expected to cut rates.

Watch this space: Substantial debt growth is taking place in Finland, Canada and Japan, which have seen the largest increase in debt-to-GDP ratios of all countries IIF tracks over the past year. Developed markets, like the U.S., Western Europe and Japan, saw total debt rise by $1.6 trillion in Q1, with debt outstanding now totaling $177 trillion.

2. Emerging market debt hits record high

Debt in smaller emerging market countries, which are now providing the majority of the world's growth, rose to a record high of $69 trillion in the first quarter, IIF reported.

Why it matters: EM debt has been growing at a breakneck pace so far this year, as global investors search for yield with developed market interest rates at or near all-time lows.

- The lower rates in the U.S., Europe and Japan are pushing increasing demand for higher-yielding EM bonds, with yields on the U.S. benchmark 10-year Treasury note at the lowest since 2016, and many European and Japanese government bonds holding negative yields.

- Increasingly countries with little to no track record and shaky fundamentals have been able to issue larger bond issues for extremely low rates.

What to watch: Net borrowing in so-called frontier markets — countries too small or underdeveloped to be labeled emerging, such as Zambia, Bangladesh and Tunisia — reached over $250 billion in 2018, bringing the total stock of FM debt to more than $3.2 trillion, according to IIF data. That was equal to 117% of frontier countries' GDP.

The big picture: This could become a problem for both the investors buying the bonds and the countries issuing them. The IMF and IIF both highlighted growing concerns about debt sustainability earlier this year, prompting calls for policy remedies including more transparency in lending to vulnerable countries.

3. Marriott says resort fees will continue

Marriott International president and CEO Arne Sorenson said in an interview Friday that so-called resort fees are not going away despite a recent lawsuit from the attorney general of Washington, D.C.

"We'll obviously fight it," Sorenson said of the lawsuit, which alleges Marriott made hundreds of millions of dollars from the fees, which are described as deceptive and in violation the District's consumer protection laws.

- By advertising a base rate for rooms and then adding the fees after customers booked a room or when they checked out of a hotel, Marriott used a practice known as "drip pricing," the complaint says.

Why it matters to the market: Resort fees have certainly helped Marriott's bottom line. Shares have outperformed the S&P 500 by 11% so far this year, rising a little more than 31% year to date, and has outperformed the S&P by around 340% over the decade-long period D.C.'s attorney general alleges the "drip pricing" scheme has been happening.

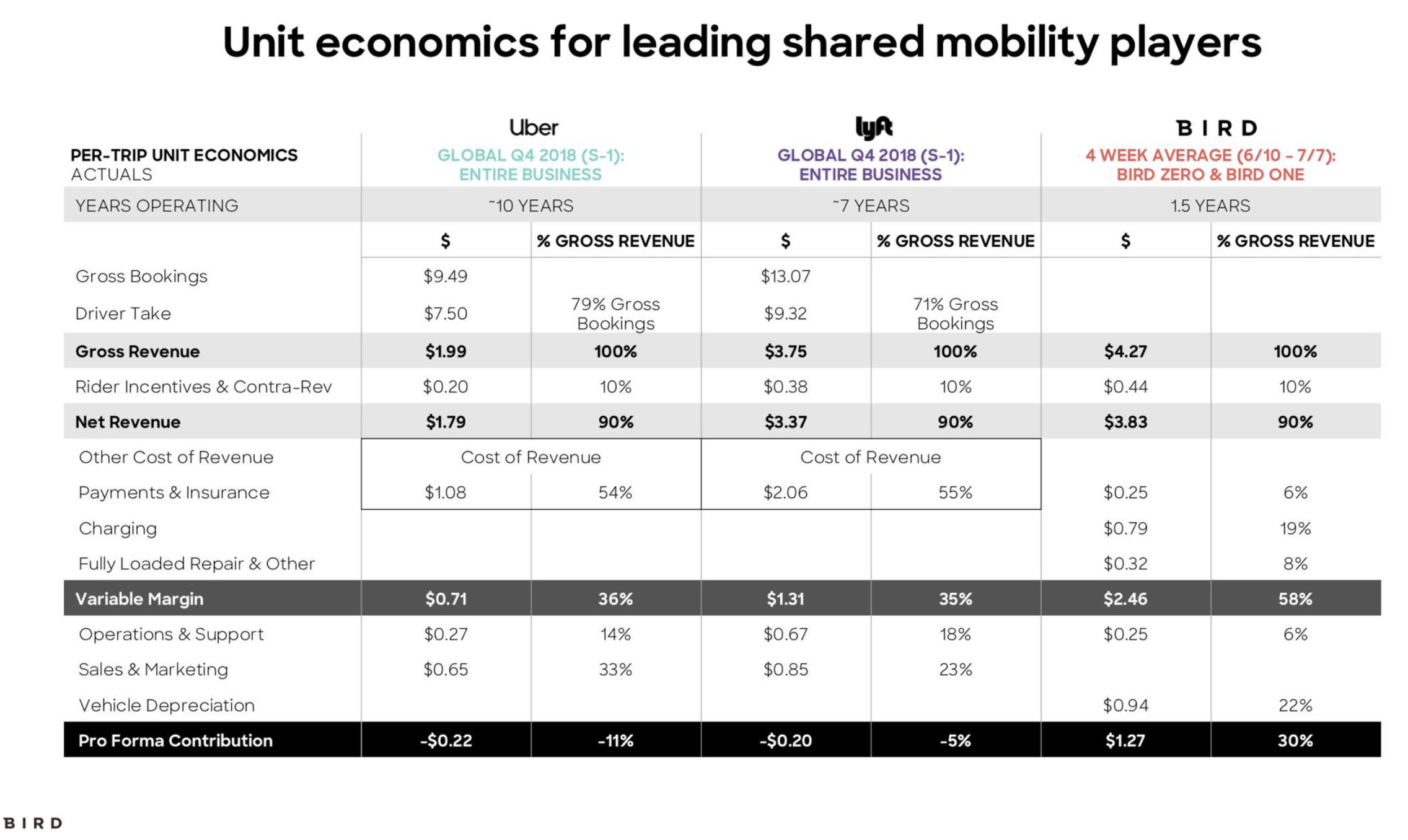

4. Bird CEO calls report of $100M loss fake news

In an effort to counter a report from The Information that his scooter company posted a $100 million loss in Q1, Bird CEO Travis VanderZanden released the above comparison spreadsheet on Twitter.

What it means: While the comparisons are incomplete and most certainly not apples to apples, Bird's revenues and margins are impressive, even given the truncated timeframe, analysts told Axios.

- VanderZanden added that the $100 million loss was a one-time "accounting write off" from depreciated vehicles purchased in 2018 and not a net loss.

- Bird chief product officer Ryan Fujiu, who previously worked for Uber and Lyft, also posted the comparison on social media.

What he's not saying: Neither Fujiu nor VanderZanden denied The Information's claim that Bird is down to $100 million in cash, after raising $700 million, and is seeking $300 million in new funding.

5. Buying a house is a bad investment

Axios' Felix Salmon writes: You wouldn't make a 5x leveraged bet on the S&P 500 — not unless you were an extremely sophisticated financial arbitrageur, or a reckless gambler.

Even then you wouldn't put substantially all of your net worth into such a bet. Stocks are just too volatile. But millions of Americans make 5x leveraged bets on their homes — that's what it means to borrow 80% of the value of the house and put just 20% down.

By the numbers: Unison, a housing-finance startup, has crunched U.S. house-price data in a paper to be released tomorrow. Over the long run, any given home is likely to experience price volatility of about 15% per year; during the height of the crisis, that number spiked to more than 35%. That's broadly in line with the kind of volatility you see in the stock market.

- Unison's results are in line with public data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency, which show annualized house-price volatility, over the past 10 years, ranging from 12% in Alaska to 17% in Hawaii, New York, and the District of Columbia.

Be smart: Annualized house price volatility is much greater than the amount you can expect a home to rise in value over the long term. That number is closer to about 4%. While homes are much less volatile than individual stocks, they're just as volatile as the kind of diversified stock indices most people invest in.

The bottom line: Any given home has roughly a 30% chance of ending up being worth less in five years' time than it is today. If you can't afford that to happen, you probably shouldn't buy.