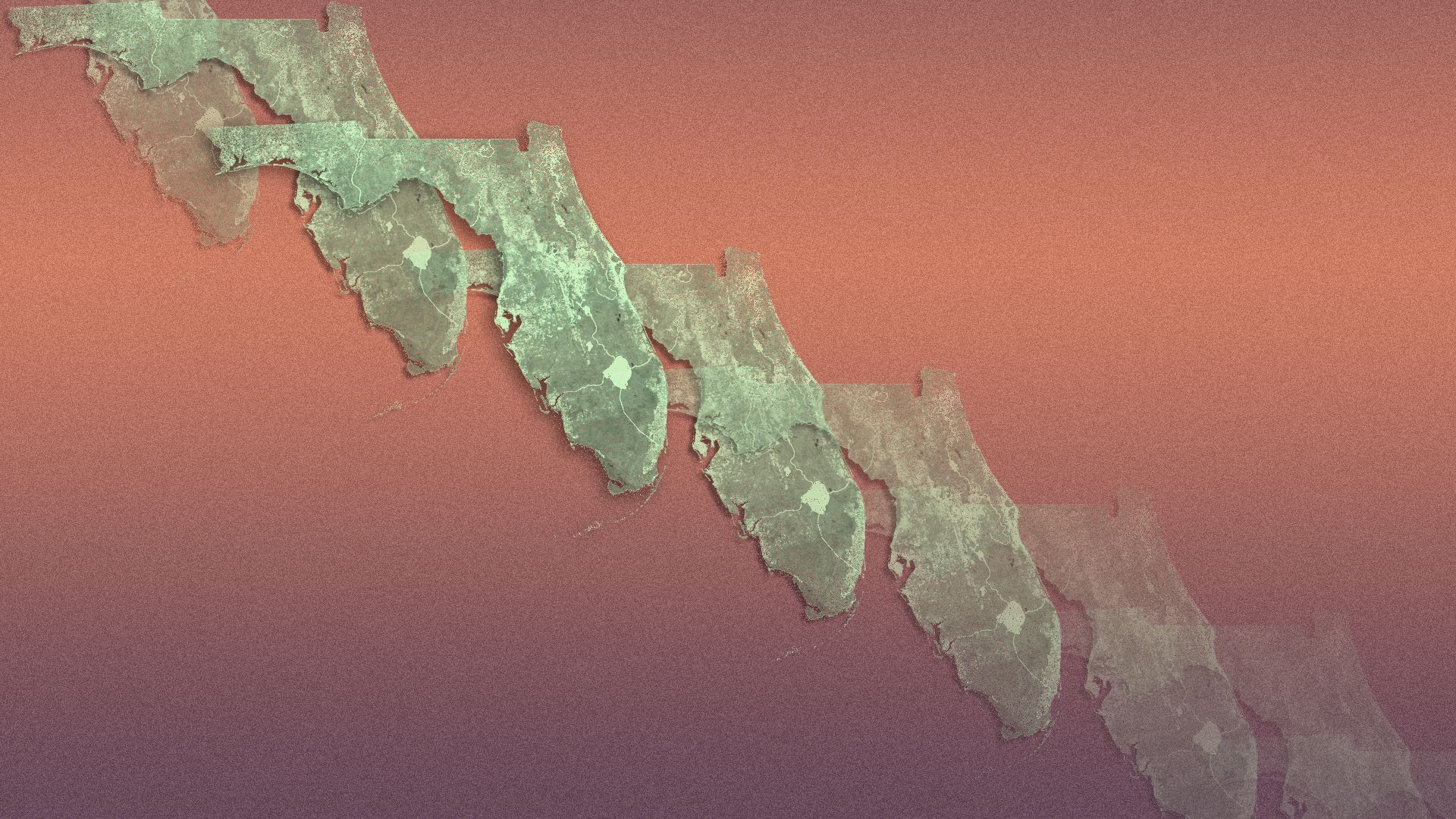

How Florida fails those with mental illness

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

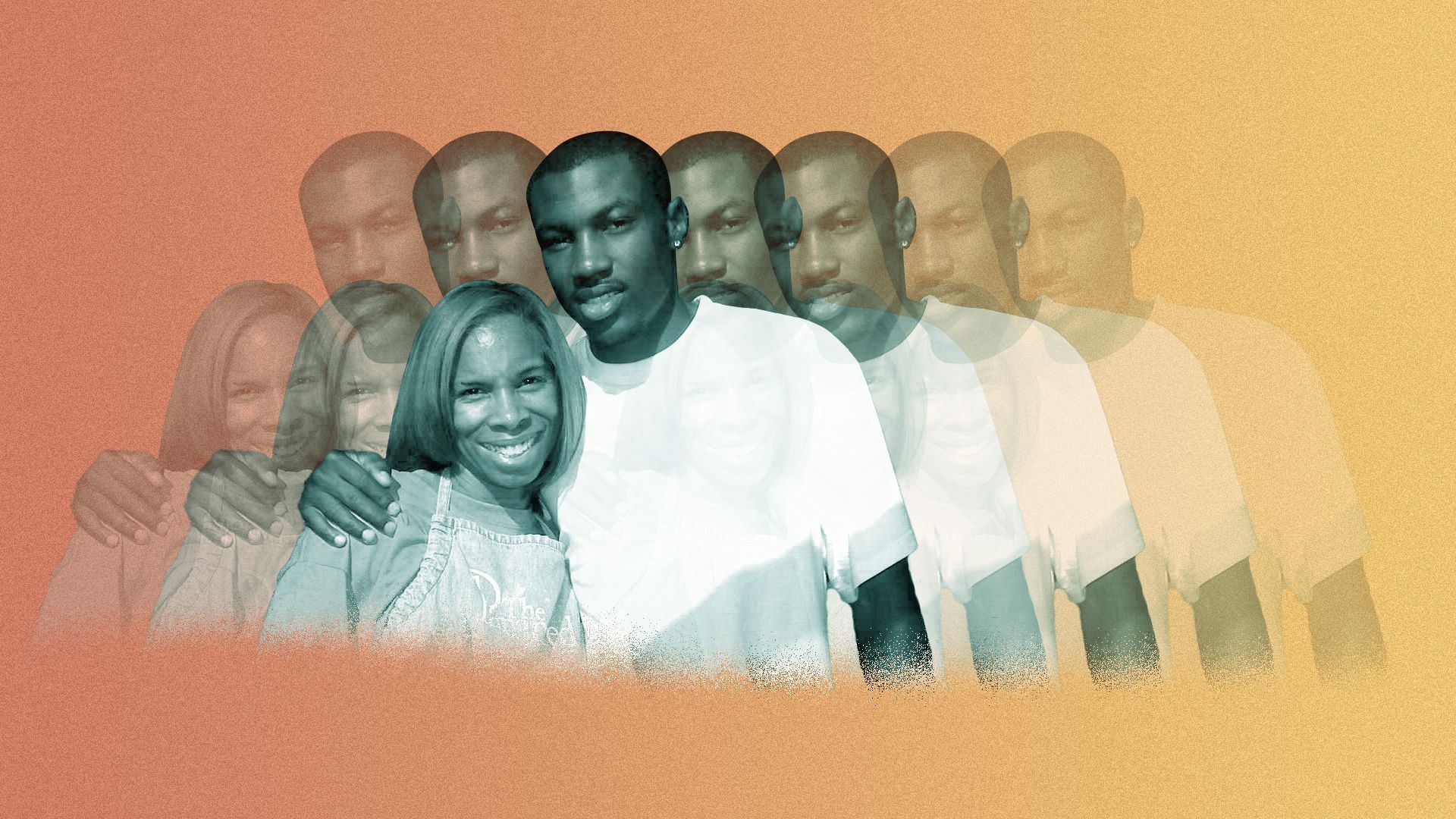

Photo illustration: Brendan Lynch/Axios. Photo courtesy of Khadeeja Morse

After 13 years of living with mental illness and three years battling in court, Mikese Morse is finally getting mental health treatment. The cost: another man’s life.

Why it matters: Mikese’s saga illustrates how Florida treats those in need of involuntary mental health care — as criminals, relying on cops and courts to solve problems that need medical intervention — with potentially tragic results.

What happened: Mikese, 33, once dreamed of representing Tampa in the Olympics as a track and field star out of USF before his mental illness derailed that plan.

- His parents say they tried to get him permanent assistance but failed, as seen in a 2017 encounter with police where they were told "being mentally ill isn’t a crime."

- But one day Mikese did commit a crime, killing 42-year-old Pedro Aguerreberry when he drove into the father and his two young sons as they rode their bicycles in 2018.

- After that, his parents say, he was treated like a criminal instead of a person with mental illness.

The big picture: About 10% to 25% of people in U.S. prisons have been diagnosed with serious mental illnesses, according to a 2014 National Research Council report. Compare that to a rate of 5% among all Americans.

- Across Florida, a Sun Sentinel investigation found people with mental illness killed or brutally assaulted at least 500 loved ones in Florida from 2000 to 2016 — while the state’s funding for mental health care declined.

- Mental Health America ranked Florida 48th nationally for access to mental health care in 2021.

Missed opportunities

Mikese spent a decade in and out of the mental health system and had several run-ins with law enforcement before the crash. But after each incident, the Morses say they were told no one could help them get him long-term treatment.

The latest: A judge ordered Mikese to be moved from prison to a mental health hospital last month, after he was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

- Mikese was diagnosed after the crash with bipolar schizoaffective disorder.

The backdrop: Mikese was Baker Acted — a temporary and often involuntary commitment to a mental health facility if one is deemed a threat to themselves or others — multiple times before the crash, according to his parents.

- In the fall of 2007, during his freshman year at USF, he was Baker Acted at St. Joseph’s Hospital by his father, Michael. He was held for 72 hours.

- In 2009, he spent two weeks at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami while attending the University of Miami.

- In 2010, he spent 72 hours at Gracepoint, a Tampa behavioral health clinic, for his third Baker Act.

On Aug. 13, 2017, the Morses say police followed Mikese after he didn’t stop for a traffic violation when police tried to pull him over.

- Mikese's mother, Khadeeja, says she asked if the police could once again help get him Baker Acted for treatment, but was ultimately told that there was nothing they could do because "being mentally ill isn’t a crime."

- "She can see it. She hears it," Khadeeja says of the interaction with police. "She can acknowledge it, and she just acknowledged every failure of the system, so that means we’re on our own."

- Neither the Tampa Police Department nor the Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office have records of this interaction, but it’s not likely they would if no tickets or warnings were written.

Less than three weeks before the crash: Mikese's parents say officers came to their home to ask about threats to then-President Trump he had made on social media on June 6, 2018.

Less than two weeks before the crash: On June 12, 2018, Mikese walked into a Tampa police station and told officers he was worried he might hurt someone. He was Baker Acted and once again taken to Gracepoint.

- The facility serves as a sort of mental health ER. When people are Baker Acted, they’re usually kept for a few days. After that, it's up to them to continue suggested follow-up treatment.

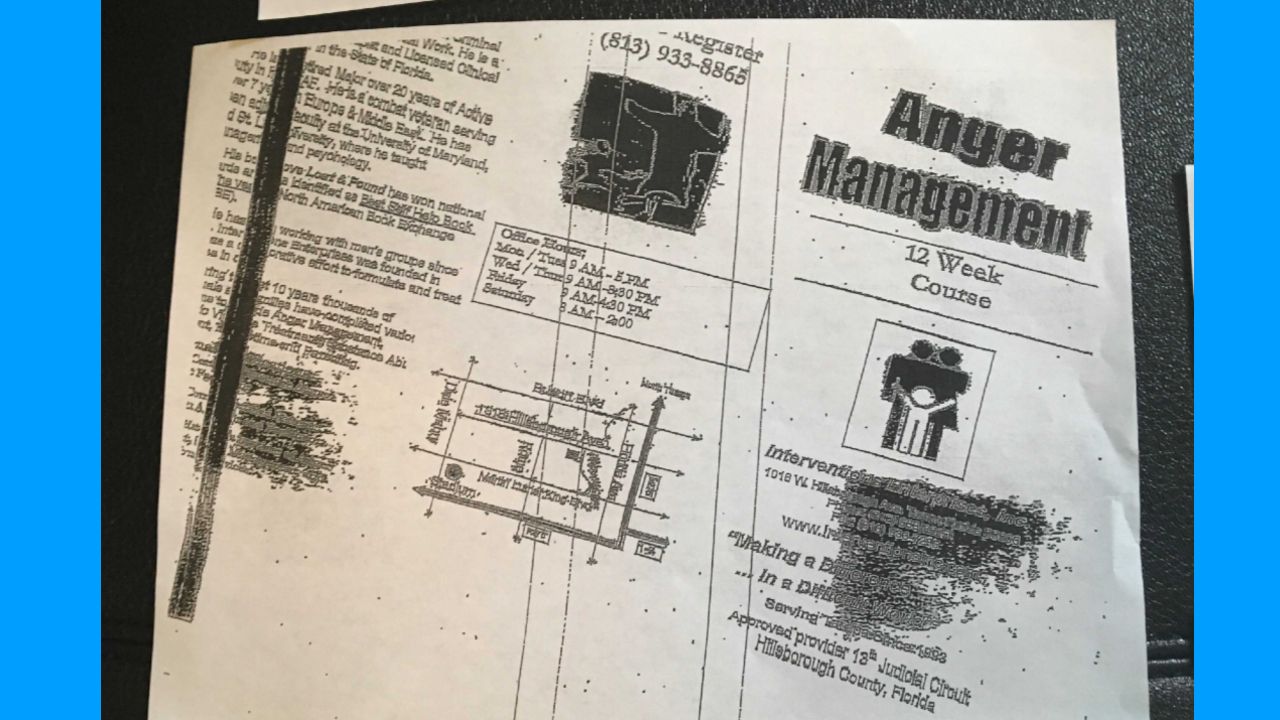

Gracepoint held Mikese for a week and released him five days before the crash with what his mother calls "a bus pass and a good luck."

- His discharge packet contained a resource guide dated 2014 and practically illegible scans of documents. Many of the places listed for housing were unreadable. Most of the others Khadeeja called were either full or listed under the wrong number.

- The facility does not share who has or has not received treatment and representatives could only speak generally.

- Gracepoint spokesperson Susan Morgan says the photos are not reflective of their discharge packets and that patients aren't discharged until they are seen by a psychiatrist and receive a follow-up appointment and any medications.

Five days after his release, Mikese ran down the Aguerreberry family.

"They really wanted to create a villain"

When TPD officers showed up at their home after the crash to arrest Mikese, the family was horrified and devastated.

- Their only hope was that this would finally be a catalyst for real long-term help — but it turned into their worst nightmare.

The final straw: Khadeeja and Michael say they talked for hours to investigators about their son’s mental health history and felt confident the police understood he had a severe mental illness, especially given that the same department had just Baker Acted him.

- But when they turned on the TV the next day, they watched then-Chief Brian Dugan say their son intentionally hit the Aguerreberry family — with no mention of his mental illness.

- Khadeeja took to the internet and did every interview she could to correct the record. "They really wanted to create a villain. If we didn’t speak, they were going to put our son in jail and not tell the truth," she tells Axios.

The other side: The TPD stands by Dugan’s initial statements after the crash. The department wouldn’t let Axios speak to Dugan, but sent a statement...

- "It’s the police department’s responsibility to arrest individuals for crimes committed. Based on the evidence, Morse intentionally ran over a father and two children at the time of his arrest."

- "The determination of the subject’s competency and placement is not the role of the investigator on scene. It is up to the justice system to determine the outcome."

A court battle

In the three years after the crash, the Morse and Aguerreberry families suffered constant delays in the case. Determining Mikese’s competency to stand trial and start getting treatment took months — and then COVID hit.

- Watching her son sit in jail was like "death by a thousand paper cuts," Khadeeja says.

- "He was decompensating in front of our eyes, and in front of their eyes and they all knew it and saw it. ... And they still wouldn’t let us get him to a hospital," she adds.

- The Aguerreberry family did not respond to Axios' requests for comment for this story.

Between the lines: That’s how the system works, State Attorney Andrew Warren tells Axios.

- Because Mikese committed a felony, his case couldn’t be moved to a mental health court.

- In order to move the case forward, Mikese needed to be deemed competent to stand trial. Then, he needed to be evaluated by experts so the court could determine whether he had an insanity defense.

- Warren blames part of the delay on Mikese’s attorney for fighting over whether he could be placed into private care instead of a state hospital.

But Warren puts the biggest share of the blame on what he calls a broken system.

- "Here you’re seeing an example of the worst type of tragedy that occurs when someone who is in dire need of mental health treatment fails to get it. This was preventable. This is an example of the failure of the mental health system in our community," he says.

Fixing a broken system

Everyone involved in Mikese's story points to a different villain.

- The police points a finger at him. Prosecutors points to the mental health system. The Morses direct their anger toward one specific place: Gracepoint.

The other side: Gracepoint CEO Joe Rutherford couldn’t comment directly on Mikese's case, but he did have a response for those who say the system is broken.

- "It absolutely isn't broken. The parts that are in place work miraculously well," he tells Axios.

- The problem in Florida, Rutherford explains, is that there are gaps of care in the mental health system that aren’t funded. And people often slip through those gaps.

- "All those components are there for successful discharge and post-treatment but once a person walks out of the unit, they’re on their own to follow up with our recommended after care," Rutherford says.

His solutions: Rutherford says Florida needs to follow the example of other states who have funded short-term residential programs. He says Gracepoint alone processes more than a thousand people a month, in addition to more than 25,000 people in its outpatient programs.

- People who are released from a Baker Act that need more than just a pre-scheduled outpatient appointment would be able to spend two to three months in supportive housing.

- It’s a program that exists in limited quantities in Florida, but hasn’t received more funding in about a decade, Rutherford says.

- "The fact of the matter is it would pay for itself. It would save the state money and take pressure off the state hospital system. It would give us that missing component that we have right now in our current acute care system," he adds.

Continuity is also a problem. Hospitals with Baker Act beds have no connected records system, so facilities can only access their own records about a patient.

- "When we have someone come through our front door, if we could see a snapshot of their history throughout the state of Florida, we would certainly be able to improve that patient’s care," Rutherford says.

The fight continues

There have been a number of recent developments around Tampa Bay aimed at improving care for those with mental illness.

- Police departments have been adding mental health resources to aid officers, a measure to help keep those in crisis out of the criminal justice system.

- TPD formed a behavioral health unit over the summer, per Creative Loafing.

- Gracepoint's no-show rates for follow-up appointments dropped significantly over the last few years, Rutherford says, after it started new outpatient orientation groups.

What’s next: Weeks after the court's order, Mikese is still waiting to be transferred to a state hospital. Khadeeja continues waiting for word from the jail, trying to understand when that'll finally take place.

- In the meantime, she says he’s well enough to be in the jail’s general population, but she won’t stop fighting until he gets treatment.

- She doesn’t plan on being quiet about his case any time soon. She won’t stop talking to reporters, posting on TikTok or speaking out in whatever way she can until her son’s name is associated with lasting change.

Her bottom line: "With every breath in my body, I'm going to keep talking about this and sharing this and exposing this. Literally there’s not a better example of the failures of the mental health system than with Mikese."

- "Every system that should have been there to protect this outcome failed — multiple times, from before it happened to right now."