Axios Science

April 11, 2019

Thanks for subscribing to Axios Science. Please consider inviting your friends, family and colleagues to sign up.

I appreciate any tips, scoops and feedback — simply reply to this email or send me a message at [email protected].

1 big thing: Where black hole research goes next

The astonishing first photo of a black hole, revealed Wednesday by the team behind the Event Horizon Telescope, opens up new avenues for researchers to probe more deeply into the inner workings of these extreme and fundamental aspects of our universe.

Why it matters: The major announcement that scientists have finally caught one on camera, so to speak, paves the way for the pursuit of new avenues in astrophysics that will probe the nature of gravity, scientists tell Axios. This work may reveal limits to Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity.

Details: One focus for scientists going forward will be trying to observe and understand the powerful jets of radiation and ultra high-speed particles that are ejected from near the black holes at close to the speed of light. It's thought that black holes are the source for some of the most energetic particles in the universe, known as cosmic rays.

Context: The photo, taken by the Event Horizon Telescope, shows the shadow of the Messier 87 (M87) galaxy's supermassive black hole surrounded by a ring of light near the object's event horizon — the point at which nothing, not even light, can escape the gravitational pull of the black hole.

- The ring consists of superheated gases known as plasma, which forms as a result of the black hole's immense gravitational field.

- The material headed toward Earth appears brighter than the side moving away.

What's next: Sera Markoff, a member of the EHT science council and theoretical physicist at the University of Amsterdam, tells Axios that even with the new discovery, scientists are still limited in their understanding of black holes.

"I’m very interested in this interface with theoretical physics, and what are black holes really?" Markoff tells Axios.

"We know that Einstein was right in a general sense, but we don’t actually understand why gravity works the way it does on a really microscopic level. How does it function? Gravity is not a force like the others … general relatively explains how it works, but it doesn’t answer the why."— Sera Markoff

Markoff says the jets that are "literally rooted in the black hole" could be used to figure out something fundamental about the nature of space-time. "So we’re not there yet, but there’s just so much that’s going to come out of this," she says.

The intrigue: "The most exciting thing we could possibly do would be to supplant Einstein, to find that in this extreme gravitational laboratory that there’s something a little new," Avery Broderick, an astrophysicist with the EHT team, said at the press conference.

- "The problem of quantum gravity remains unsolved with the current tools that we have. Black holes are one of the places to look for answers," Broderick said.

Where it stands: Currently, EHT consists of 9 radio telescopes at 7 sites, including those in Antarctica and Greenland.

- The EHT team is planning to add 2 more to the mix by 2020 and is putting together proposals for a space-based telescope to boost capability for probing the secrets of black holes.

Go deeper:

2. Quote of the week

EHT project director Sheperd Doeleman, University of Arizona's Dan Marrone, Avery Broderick and Sera Markoff (l to r) at April 10 news conference. Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

"Sometimes the math looks ugly. But really, there’s a strong aesthetic in theoretical physics ... and the Einstein equations are beautiful. And so often in my experience, nature wants to be beautiful."— Avery Broderick

Context: Broderick was speaking at the press conference about how the EHT's results proved Einstein right yet again. Even though Einstein did not believe black holes existed, his theory of general relativity describes how they function.

Why it matters: This reveals how theoretical physicists like Broderick view Einstein's theory of general relativity, and how it's held up over time. He went on to say that further exploration of black holes, using the EHT, may yield new information that runs counter to Einstein's findings.

3. Examining wonder drug ketamine

Illustration: Lazaro Gamio/Axios

An important way to prevent depression relapse could be to figure out how to maintain parts of neurons in the brain known as dendritic spines, according to a study out today, Eileen Drage O'Reilly reports.

The study in mice, published in the journal Science, examines ketamine, an antidepressant that's getting a lot of buzz.

Why it matters: Depression affects nearly 20% of Americans — 80% of whom will endure a relapse after remission and 30% of whom will have treatment-resistant depression.

- Ketamine has been lauded for alleviating treatment-resistant depression in an extremely short amount of time — but the side effects are quite serious, no one knows exactly how it works, and the positive effects don't last long.

What they did: Study author Conor Liston tells Axios the research team essentially did two experiments after the first one found "the formation of synapses are important ... but not in the way we thought."

- The first experiment compared the timeline of the formation of new spines in the neurons with the effect on behavior after ketamine was given.

- The ketamine had a positive effect on depression and led to increased neural activity in about 3 hours, but the new synapses did not form in the brain until 12 hours or later, says Liston, associate professor of neuroscience and psychiatry at Cornell.

- They then joined with the University of Tokyo, which developed a new imaging tool to watch dendritic spines in neurons in mice, which were stressed to produce reactions similar to depression in humans.

What they found: Stress caused the mice to lose some synapses in their brains, but these were mostly restored after given ketamine, Liston says. The tool then erased the newly formed synapses to see how behavior changed — and the mice reverted to their prior "depressed" behavior.

What they're saying: Liston says the findings indicate that ketamine's antidepressant effect could last longer if interventions can be created that enhance and protect the new synapse formation.

- "Studies like [this one] are absolutely critical for understanding ketamine's novel mechanism of action so that we can develop next-generation versions of ketamine that are even safer and more effective," David Olson, assistant professor at UC Davis who was not part of this study, tells Axios.

Go deeper:

4. The new Arctic is roasting Alaska

The Arctic region has been pushed into an entirely new climate, one that's outside the experience of longtime residents and native wildlife, shows a new report in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

Why it matters: The far north is undergoing profound changes that are affecting the rest of the world, from the melting of permafrost, which releases greenhouse gases, to the disappearance of sea ice.

The big picture: To understand how unusual and consequential Arctic warming is, one need only to look at recent events in Alaska, which this year experienced its warmest March on record, and warmest October through March. In fact, Alaska has had its warmest 6 years on record, too.

Details: People across the state are coping with an unusually early start to spring, according to Dave Snider, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Alaska.

- This means ice breakups on rivers, life-threatening hunts for food in native communities and many other impacts.

- The likelihood that Utqiagvik (formerly known as Barrow) would reach those March average temperatures was just a 1-in-250,000 chance of occurring in a given year, Snider tells Axios.

Between the lines: In Talkeetna, north of Anchorage, workers who produce birch syrup had to be called in on an emergency basis, several weeks earlier than normal, because temperatures were rising so quickly, Snider says.

- Snider thinks the Nanana ice tripod — a webcam of a big stick in the middle of a frozen river — will melt out early this year.

- The earliest date on record is April 20, Snider says.

March is no fluke. “It doesn’t appear to be a one-off if you do the stats,” Snider says.

The bottom line: A new Arctic has emerged during the past 40 years, and Alaska is experiencing that firsthand.

- Due to higher air and sea temperatures, land-based ice in Alaska is being lost at the rate of about 14,000 tonnes per second, William Colgan, a co-author of the study, tells Axios.

- "This report is part of an emerging genre of climate reports sounding the claxon that the future is now in terms of virtually all observable Arctic climate indicators."

5. New lymphoma treatment shows promise

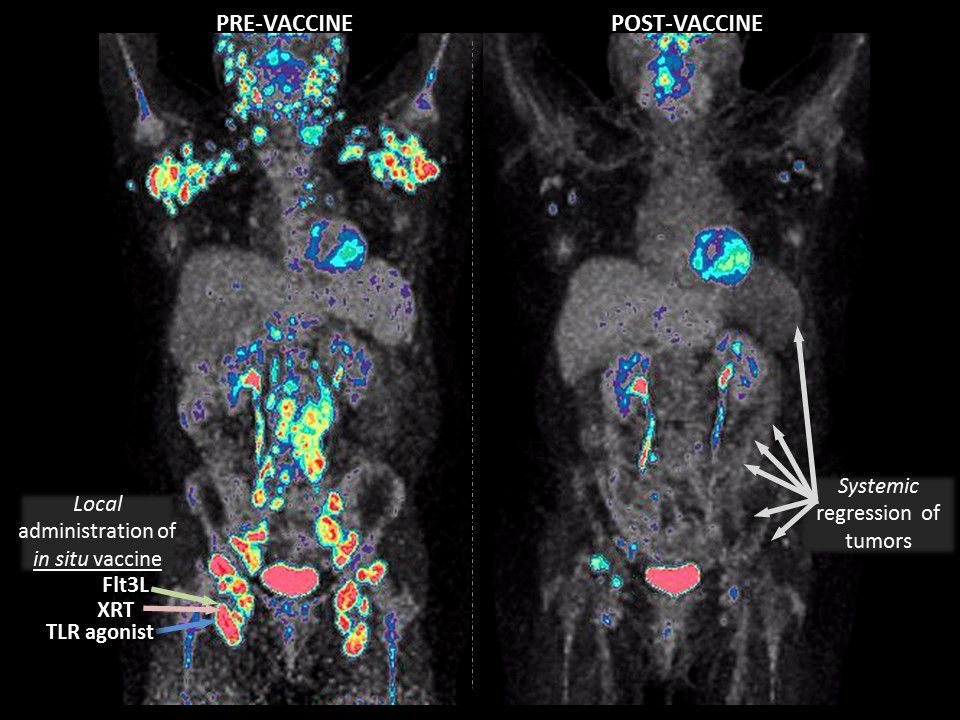

Scientists announced a preliminary success in devising a cancer "vaccine" that was able to help prime the immune system to attack lymphoma cancer tumors in some patients, leading to a period of remission, according to a small clinical study, Eileen writes.

Why it matters: Indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (iNHL) tends to be a slow-growing cancer that is incurable with standard therapy and responds poorly to a newer type of treatment called checkpoint blockade.

- Scientists are seeking ways to broaden the response of immunotherapy to more patients, and a therapeutic cancer vaccine is one option they're chasing.

Background: Dendritic and T-cells both play powerful but distinct roles in the immune system. Dendritic cells detect an infection or cancer cells and alert the T-cells to attack en masse.

- But cancer cells often elude discovery by the immune system for a variety of reasons.

- This new type of treatment is designed to force the tumor to expose itself and trigger the immune response.

What they did: The trial, which began in 2013 and was published in Nature Medicine Monday, tested a three-pronged attack as part of the treatment. The tests were done first in animals and then in 11 human patients, most of whom had iNHL, says study author Joshua Brody, director of the lymphoma immunotherapy program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital.

- The treatment was injected into one of the tumor sites to spur the tumor to make a therapeutic "vaccine" that triggers the immune system.

How it works: Each of the 3 components in the treatment plays an important role, Brody says. Separately, each have shown modest improvements in patient outcomes, but together they show a stronger impact.

- The components recruit dendritic cells to the tumor and help the immune system identify the threat by activating the body's detection system.

- The ultimate goal is to have T-cells proliferating and spreading throughout the body to kill any cancer cells.

What they found: The mouse trial was robust and successful, while the trial in the human participants showed a strong response in some, but not all, patients.

- The "vaccine was dramatically successful in some patients, with partial and complete remissions (of non-injected tumors) lasting for months to years," Brody says.

- For non-responders, they found the patients still had developed new T-cells and their tumors had become responsive to a type of treatment called PD1 blockade, prompting a followup trial of the combined therapy.

What they're saying: Several experts who were not part of this study tell Axios it shows some promising results, but also caution that the study was small and only helped some of the patients.

Go deeper: Read more of Eileen's story.

6. Israel's attempt at lunar landing history fails

Beresheet looking back at the Earth after launch in March. Photo: SpaceIL/IAI

The Israeli Beresheet lunar lander didn't stick its potentially historic moon landing on Thursday, suffering from a main engine failure in the final moments of its descent.

Why it matters: Had it not crashed, Beresheet would have been the first privately funded spacecraft to land on the moon's surface and the first for Israel. In spite of the failure, this historic mission shows that space is slowly but surely becoming more and more accessible.

The big picture: SpaceIL — the non-profit behind the mission — wasn't backed by a government, but instead raised money for the mission through donations from wealthy philanthropists.

- Only the U.S., China and Russia have successfully soft-landed on the moon.

- The mission also highlights just how difficult it is to successfully launch a relatively inexpensive mission to the moon.

Background: SpaceIL originally conceived of the mission to compete for the Google Lunar X Prize — a $30 million contest to encourage private industry to pave a commercially-sustainable path to the moon. That contest ended without a winner in 2018.

- Before its failed landing, the lander sent back this selfie.

What they're saying: Newly re-elected Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was on hand for the landing. "If at first you don't succeed, you try again," Netanyahu said after the mission's failure.

- "We didn't make it, but we definitely tried," said Morris Kahn, one of Beresheet's financial backers.

- "Space is hard, but worth the risks. If we succeeded every time, there would be no reward," NASA associate administrator Thomas Zurbuchen said on Twitter.

7. Axios stories worthy of your time

Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios

Bones discovered in Philippines may have belonged to new human species (Gigi Sukin)

Paralyzing blizzard slams the Plains, Midwest with 2 feet of snow

Podcast: America's return to the moon (Dan Primack and Miriam Kramer)

"Cosmic cartography" gets a jump start (Miriam Kramer)

The new space race (Miriam Kramer)

A worldwide census from the sky (Kaveh Waddell)

8. What we're reading elsewhere

Meet Katie Bouman, One Woman Who Helped Make the World's First Image of a Black Hole (Katy Steinmetz, Time)

A Mysterious Infection, Spanning the Globe in a Climate of Secrecy (Matt Richtel and Andrew Jacobs, NYT)

New York’s Orthodox Jewish community is battling measles outbreaks. Vaccine deniers are to blame (Julia Belluz, Vox)

Earth’s grasslands are vanishing. See the wildlife that calls them home (Natasha Daly, NatGeo)

9. Something wondrous: The California super bloom

Aerial photo of wildflowers blooming in California's Antelope Valley in April. Photo: Jim Ross/NASA

Copious amounts of winter rainfall led to one of the biggest blooms of wildflowers in the California desert in years. The flowers were so abundant and bright that they were visible from space.

This photo, however, was taken at a far lower altitude, from aboard a NASA T-34 airplane flying above the Antelope Valley of California on April 2. It was published on NASA's main website on April 10 and shows both yellow wildflowers and orange poppies, which is the state flower.

Thanks for reading! See you back again next Thursday. Have a great week!

Sign up for Axios Science

Gather the facts on the latest scientific advances