Why Coloradans should remember Camp Amache's history

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

The Amache Camp in Granada, Colorado. Photo: Hyoung Chang/MediaNews Group/The Denver Post via Getty Images

Tucked away in far southeastern Colorado, some 10 miles from the Kansas border, the remnants of Camp Amache still loom over the grassy plains.

Details: More than 7,000 Japanese Americans and people of Japanese ancestry were imprisoned there during World War II, according to University of Colorado Boulder history professor William Wei.

- It was one of 10 sites established by the federal government across the country following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Wei said Amache was among the smallest in the United States.

- People were brought to the camps largely from outside Colorado, mainly from the West Coast.

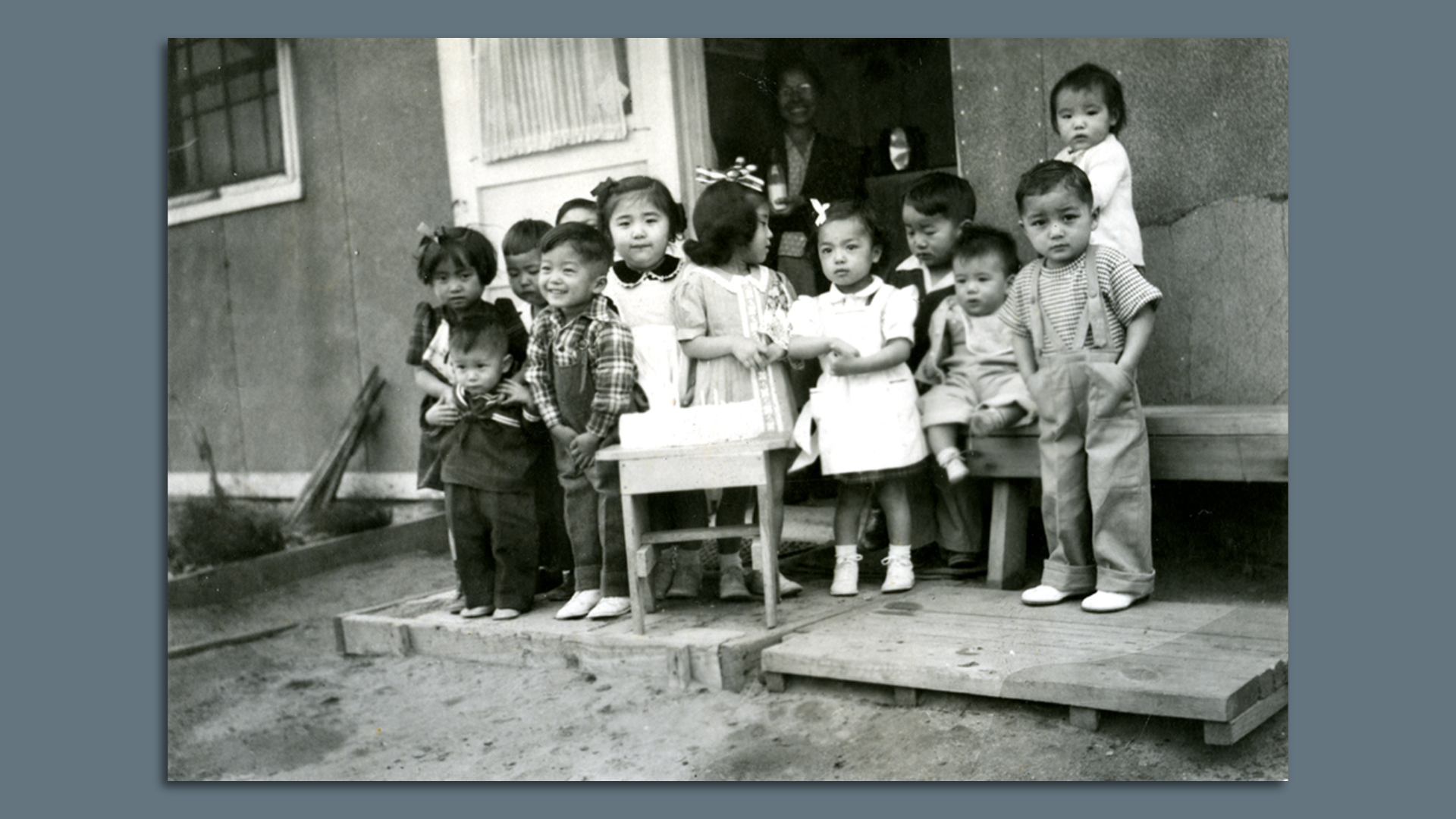

Why it matters: The site is a reminder of a dark chapter in Colorado's history where thousands of people — including children — were detained due to a false suggestion that they were a national security threat.

State of play: Wei sees parallels between the camps and the recent rise in anti-Asian American hate crimes.

- He says both periods involve Asian Americans being viewed as foreigners, even if they were born in the United States.

What they're saying: "We're fighting a war to oppose racism, and at home, we engage in racist behavior," Wei tells us, referencing World War II.

- He is specific about the language he uses for Amache, calling it a concentration camp, though it was called a "relocation center" when it first opened and the federal government now calls it an "incarceration site."

- People languished in the camps, he said, and had little privacy; it led to a "collapse" in family life for those living there.

- "The imprisonment of Japanese Americans in these concentration camps ... is considered by historians to be one of the worst mass violations of the civil liberties of Americans," Wei said.

Yes, but: Wei notes the facilities differed from those in Europe, which included forced labor and death camps.

Zoom in: Since 2008, University of Denver anthropology professor Bonnie Clark has completed archaeological research at Amache, which she said covers roughly 30 city blocks.

- People in the camps were primarily farmers and vegetable growers from California.

- Her research looks at how people developed the soil, and she's personally chronicled the growth of a rose bush flower at the camp not seen there for nearly 80 years.

Of note: Last year, President Biden signed a bill turning the still largely intact camp into a historic site, officially making it part of the National Park System.

- The designation protects it and ensures the history of Japanese American incarceration is preserved, according to a statement from the Interior Department.

- Bob Fuchigami, who was 11 when he and his family were sent there, told CPR News last year he has waited for years to see Amache become "a place of reflection, remembrance, honor, and healing."