Invasive fungi recognized as a global threat

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

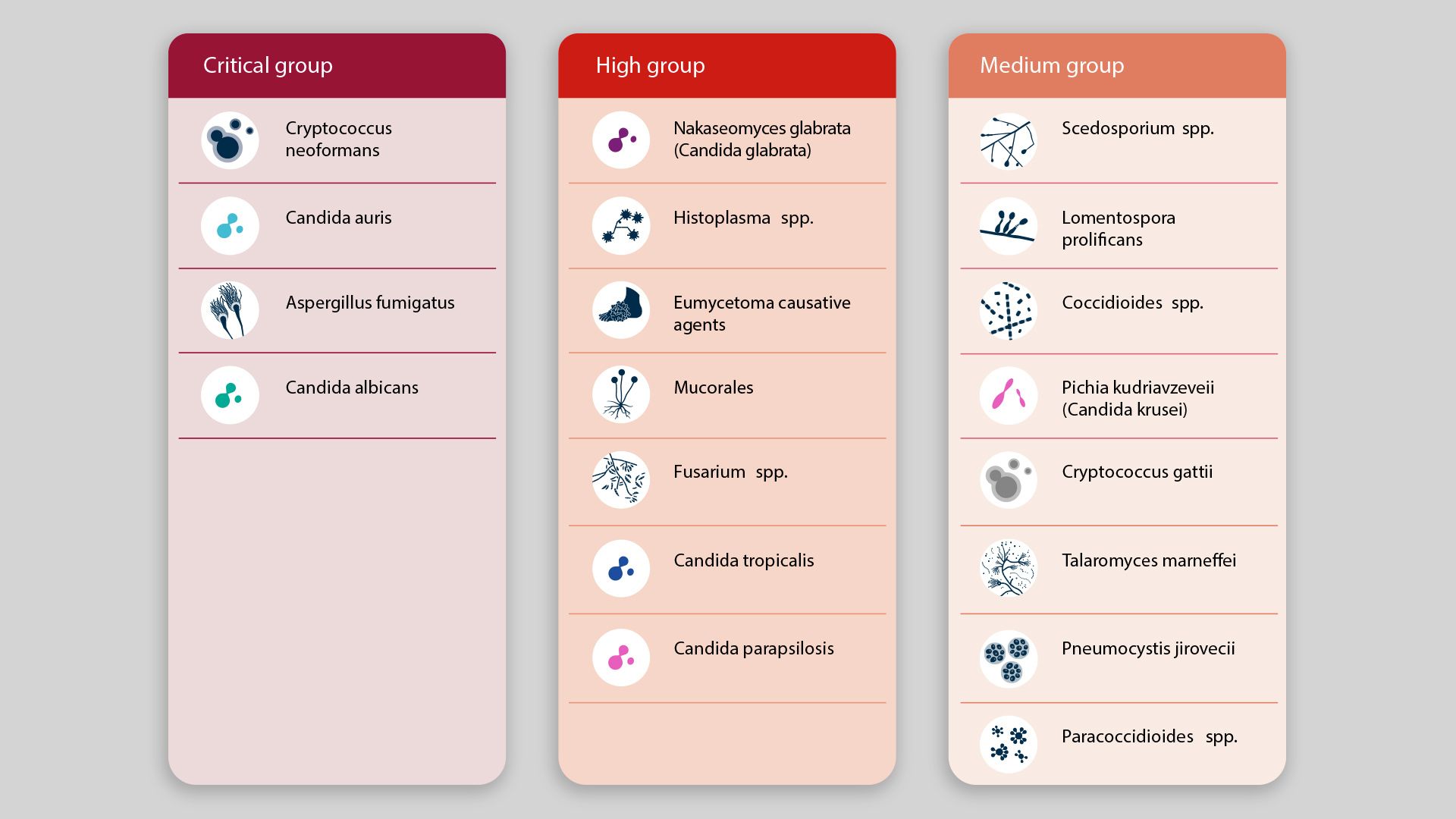

Source: WHO's fungal priority pathogens list

The dangers posed by growing outbreaks of opportunistic fungi that kill 1.6 million people globally every year require new drugs, diagnostics and surveillance programs, a CDC scientist tells Axios.

Driving the news: The pandemic accelerated the rise of drug-resistant fungi in health care settings, and global warming has expanded the range of fungi growth in certain areas — problems flagged by the WHO, which released its first-ever list of dangerous fungi last week.

What's happening: Fungi are "smart, tough organisms that are here to stay" and are evolving to take advantage of a growing immunocompromised population living in a world increasingly hospitable to certain pathogens due to climate change, says Tom Chiller, head of the CDC's Mycotic Disease Branch.

- "It could be a new species emerges and finds a niche in the environment and then happens to find an opportunistic host, and suddenly you see this new, weird infection," Chiller says.

- "We're in an era now of unprecedented emergence of fungal diseases not only in humans but also in agriculture and animal husbandry," says Cornelius Clancy, infectious disease doctor and professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh.

Zoom in: "In recent years, the epidemiology has shifted. We've seen the emergence of new fungi that previously were not recognized as causes of human infections or rare cases that have now become more prominent, and also the emergence of antifungal drug resistant fungi," Clancy tells Axios.

- Chiller points to Candida, which is in our mouth, intestines and skin but can sometimes invade the bloodstream and cause sepsis and other complications. Over the past decade, though, Candida auris has become more drug resistant and shown new characteristics, Chiller says. "This is a Candida that's actually transmitting, from patient to hospital environment to patient. ... That was really a sea change for us."

- Another threatening development is seen in Sporothrix brasiliensis, a dimorphic fungus that usually exists in different forms as either a mold that can be infectious when it's in the outside world or as a yeast once it's inside a human or animal body and not infectious to others.

- However, Chiller says there have been cases in Brazil where cats with S. brasiliensis give it to the vet via "spores flying out of their lesions into the vet's eyes, and these veterinarians were coming down with ocular sporotrichosis ... We've never heard of a dimorphic transmitting like that."

Between the lines: Humans and fungi are both eukaryotes, which makes it harder to target drugs for fungi without hurting human cells as well, and complicates efforts to create diagnostics that can easily identify the difference.

What's next: Chiller and Clancy say they are hopeful a new class of fungal drugs will be created — as some fungi have become resistant to all of the available classes of drugs. There have been some positive developments in the pipeline.

- More effort is needed as well for diagnostics and a global surveillance system. They hope the WHO's fungal priority pathogens list will provide impetus.

Go deeper: The growing threat of drug-resistant, invasive fungi