A tale of two direct listings

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

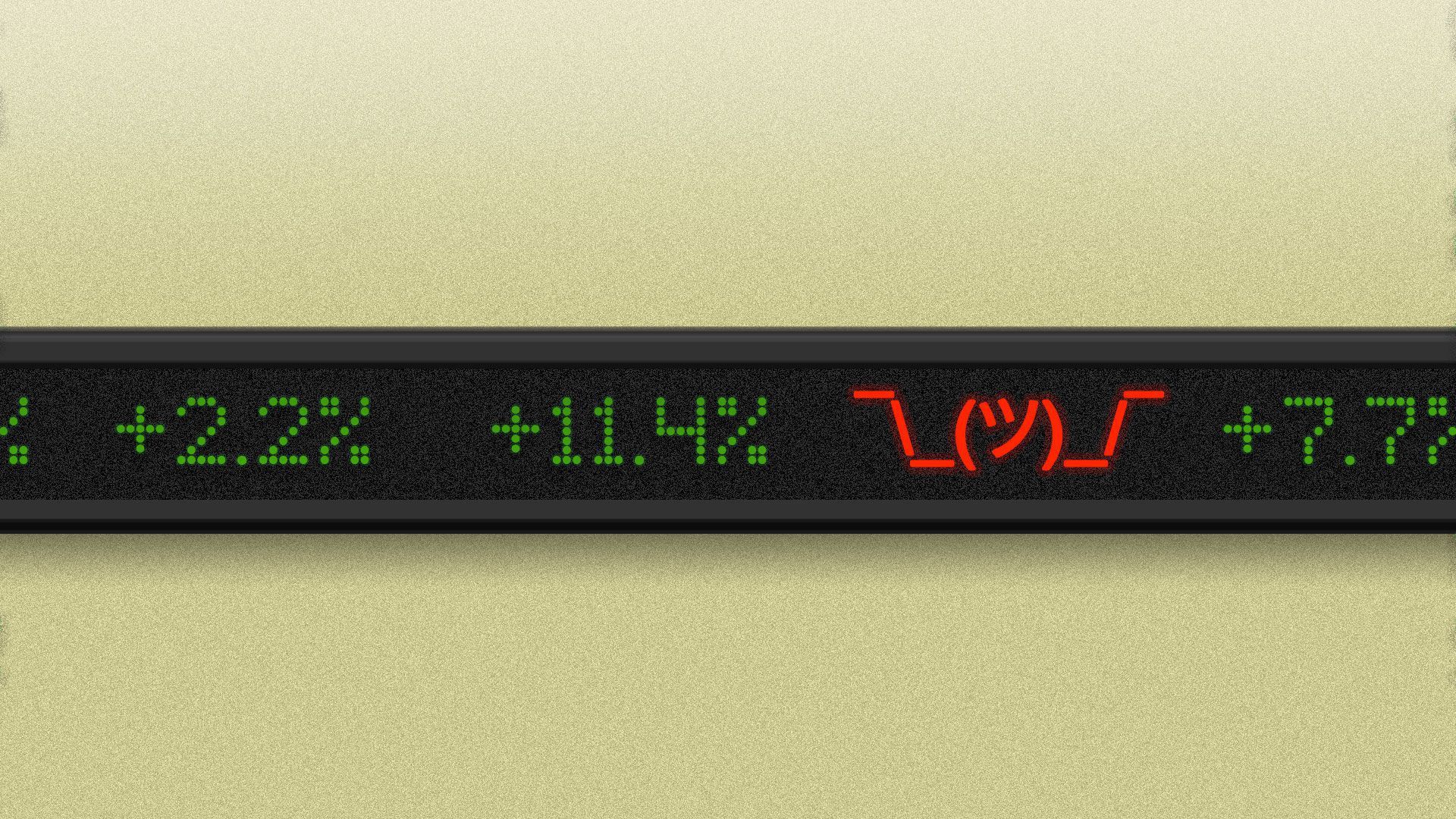

Illustration: Lazaro Gamio/Axios

This was a big week for you, if you're a Facebook billionaire looking to take your money-losing post-Facebook company public by doing a direct listing of shares on the New York Stock Exchange.

Details: Asana was founded by Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz in 2008; Palantir was founded by Facebook investor and board member Peter Thiel in 2003. Both companies released their full financials this week.

- Moskovitz, who still owns some 32 million Facebook shares worth almost $10 billion, also owns 36% of Asana. A high-profile Democrat, he is married to former Wall Street Journal reporter Cari Tuna, and has pledged to give away nearly all of his wealth.

- Thiel, who has sold all but a handful of his Facebook shares, owns just under 19% of Palantir. A high-profile Republican, he is very close friends with former Wall Street Journal reporter Alexandra Wolfe, whom he installed as a board member of Palantir. His idea of philanthropy is suing a journalistic outlet to run it out of business.

Both men own super-voting shares that give them much more control over their companies than their economic stake would imply.

- So long as that share structure remains in place, neither company will be eligible to join the S&P 500.

Asana has a leadership coach, Diana Chapman, who told Forbes that "I don't think I've ever heard them speak about profits." The company lost $118.6 million in fiscal 2020, more than double its losses the previous year, and has an accumulated deficit of $365.6 million.

- "We do not expect to be profitable in the near future," says the company in its stock-market filing, "and we cannot assure you that we will achieve profitability in the future."

Palantir lost $580 million in both 2019 and 2018.

- "We have incurred losses each year since our inception," writes the company, "and we may never achieve or maintain profitability."

Neither Asana nor Palantir is likely to raise any new capital as part of its direct listing. That's partly because Palantir raised $500 million as recently as July, and it's partly because raising money through a direct listing was illegal before yesterday.

Driving the news: The SEC now allows companies to raise new money as part of a direct listing — what I called a "direct listing IPO" last year, when Axios' Dan Primack and I were wondering whether such a thing would ever happen.

How it works: The NYSE structure receiving the SEC's stamp of approval is not the kind of hybrid model that Dan envisioned last year, in which companies would be able to allocate shares to investors like they do in a traditional IPO.

- Instead, the company will simply promise to sell a certain number of shares at the auction that kicks off the first day of trading.

- The company can set a minimum price below which it won't sell — but if the company doesn't sell its own stock, then the whole listing is abandoned, and nobody is allowed to buy or sell the stock.

- The company's share offer gets priority — those shares will be the first to be sold.

The upside of this system for issuers is that they don't "leave money on the table" when a stock "pops" on its first trade. Whatever price the market sets is the price the company receives.

- The downside is that the company has no idea how much money it's going to end up raising until after the auction is over.

The bottom line: Airbnb expressed interest in a direct listing in the pre-pandemic days before it had to lay off a quarter of its workforce. Now that it's finally going public, maybe this kind of direct listing IPO will prove attractive.

- Remember when Silicon Valley's "new mantra" was "make a profit"? Amazingly, that was less than a year ago.