Bluetooth-based coronavirus contact tracing finds broad support

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

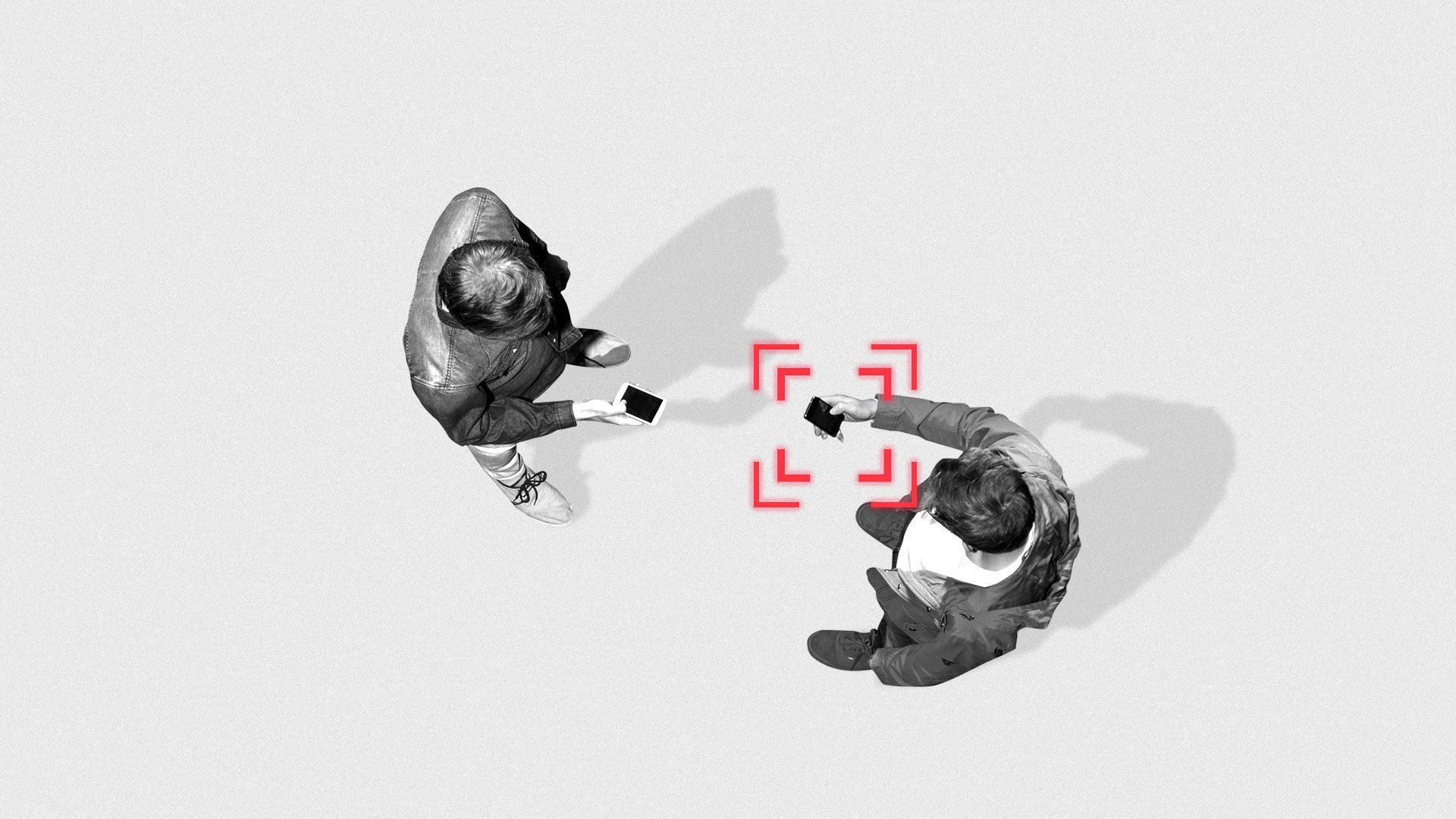

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

Consensus seems to be building globally around the idea that Bluetooth-based contact tracing could be a practical use of technology to contain the spread of the coronavirus.

Why it matters: Both governments and advocacy groups agree that using Bluetooth to sense the proximity of users' phones could be more effective and less of a civil rights problem than tapping location-based data that apps and service providers often collect.

Driving the news:

- The EU on Thursday said that mobile apps can help slow the spread of the disease, when combined with ample testing and medical care resources. But it cautioned that such apps need to be interoperable and also protect privacy.

- The EU runs the globe's strictest privacy regime, so the guidelines it has offered suggest a path forward for the Bluetooth-based approach.

- The American Civil Liberties Union offered up its own guidelines on Thursday, calling for apps that minimize data retention and central storage, augment human contact tracing and are, among other things, voluntary, non-discriminatory, and built with input from health professionals. They should also be narrowly tailored to this epidemic and their use should end when the pandemic ends, or if they are shown to be ineffective at slowing its spread, the group said.

The big picture: A number of entities are working on similar technology approaches that would appear to be able to meet the goals outlined by the EU and ACLU.

- Most prominently, this includes the joint Apple-Google effort announced last week, which aims to build a foundation for Bluetooth-based contact tracing in both the iOS and Android smartphone operating systems.

- Other efforts include the PACT project from MIT and those from several groups in Europe.

Yes, but: Any contact-tracing approach — those above or something new — will need widespread adoption to be of much use.

- Privacy advocates have argued that people need to trust the system or it won't be widely used enough to have an impact.

- Widespread testing is also a prerequisite. Contact tracing can't work unless people actually know they are infected so they can alert others.

Meanwhile: Pew reported in a new survey that Americans are not only divided on whether they find tracking apps acceptable, but are also skeptical such apps will really be effective.

What they're saying:

- ACLU staff technologist Daniel Kahn Gillmor told journalists Thursday that he is glad to see invasive location-tracking apps fall by the wayside as momentum builds for apps that use Bluetooth-based proximity. "None of them are perfect but they are substantially better than these attempts at location-specific tracing," Gillmor said.

Go deeper: