Axios Future

May 13, 2019

Have your friends signed up?

Any stories we should be chasing? Hit reply to this email or message me at [email protected]. Kaveh Waddell is at [email protected] and Erica Pandey at [email protected].

Okay, let's start with ...

1 big thing: Beating the superforecasters

A former forecasting method. Photo: Topical/Hulton/Getty

Four years ago, a team of researchers linked to the University of Pennsylvania wowed the U.S. intelligence community by producing a superior new way to forecast geopolitical events. They were dubbed the "superforecasters."

- Now, at a time when the science of professional prognostication is sorely battered, the radical innovation arm of U.S. intelligence services is looking to best the UPenn team with a fresh big-money prize competition.

What's happening: IARPA, the research arm for the U.S. director of national intelligence, is offering $250,000 in prize money in a contest to forecast geopolitical events such as elections, disease outbreaks and economic indicators.

- The contestants will have access to all of IARPA's data on the winning UPenn methodology.

- They can do anything they want — use a computer, or no computer, and any methodology.

- Over the coming eight or so months, they will be asked hundreds of closed-ended questions, such as: "How many missile test events will North Korea conduct in August 2019?" and "What will be the daily closing price of gold on June 2019 in USD?"

I asked Seth Goldstein, an IARPA program manager who is running the contest, his dream outcome: "I am hoping to find the next Swiss patent clerk doing forecasting in his spare time," he says.

- If you are that Einstein, go here to enter.

Background:

- There is substantial rigor to current forecasting, but it is still more an art than a science: "It is largely practiced by an informed elite predicated on gut instinct and intuition, and a range of confirmation biases," says Samuel Brannen, director of the Risk and Foresight Group at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

- "It’s one thing for algorithms to time market moves and execute trades faster than humans would be capable, and quite another for them to forecast the outcome of U.S.-China trade negotiations, in which the variables are nearly infinite and perhaps impossible to identify," Brannen says.

But from 2011 to 2015, IARPA ran another forecasting contest. That's the one that was won by the UPenn team, led by social scientist Philip Tetlock.

- Tetlock, who had been studying forecasting methods for decades, pushed his team of some 2,000 volunteers to be open-minded, and he championed outsiders with no particular subject matter expertise.

- Then he culled out a small group that seemed to be preternaturally terrific prognosticators. He called them superforecasters (and in 2015 co-authored a book about the methodology called "Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction").

- Tetlock declined to comment for this story.

Goldstein calls Tetlock's performance the "gold standard." But now he wants to do better.

- The contestants will be pitted against another team of expert forecasters randomly assigned to work with machines on prognostications.

- The maximum $153,000 prize can be won if a team comes in first place and performs at least 20% better than Tetlock's team, and no one else performs at all better. "They get a really nice chunk" of money "plus all of the glory," Goldstein says.

Members of Tetlock's group have added to their forecasting renown. Regina Joseph, a Tetlock superforecaster, built a cybersecurity forecasting training program for the Dutch National Cyber Security Centre, in addition to a tournament that launched last year and is still underway.

- In terms of what forecasting advances might come next, Joseph tells Axios that she would like to see "longitudinal tournaments," in which subject matter experts are pitted against generalist elite forecasters.

- "So far, results suggest good forecasting skill can still beat subject matter expertise in niche areas," she says.

Go deeper:

2. Spinning startups out of Amazon

As they've boomed, Silicon Valley giants like Uber, Google and Apple have turned into startup factories. But Amazon — with a few notable exceptions in Hulu, Instacart and Flipkart — hasn't had many cases of alums leaving to become founders, Erica writes.

Now Amazon is promoting entrepreneurship — even offering funding — and encouraging employees to start companies, but only if they are in service of the e-commerce giant.

What's happening: Amazon is paying employees $10,000 plus three months of pay to quit and start small businesses that deliver Amazon packages.

- "We’re looking to add hundreds more new businesses this year," an Amazon spokesperson tells Axios.

- Although the incentives are only available to Amazon employees, anyone is welcome to apply to start a delivery business for the behemoth, the company says. Milton Collier, a freight broker in Atlanta, tells AP he has 120 employees and 50 vans that deliver Amazon boxes every day.

- A flurry of small businesses that exist solely to serve Amazon's shipping ambitions will make the giant's logistics arm even stronger. As we've reported, the company is already turning into a formidable competitor for UPS and FedEx.

The bottom line: Amazon is creating an ecosystem distinct from its Big Tech brethren.

- The bulk of companies that are spun out of Uber, Google and others are unrelated to those firms' core businesses, but Amazon wants to fuel the creation of startups that help make it stronger.

- While many Amazon managers and executives tend to stay with the company long term, dozens who have left have gone on to start retail consultancies that advise merchants who sell on ... Amazon.

Go deeper: Amazon's delivery army (Axios)

3. The esports boom

Esports fans. Photo: Daniel Reinhardt/dpa/Getty

A new infographic from the Visual Capitalist charts the precipitous rise of esports and the resulting tangled web of sponsorships, syndications and events, Kaveh writes.

- Since 2017, the gaming industry has been more than double the size of the music and film industries.

- It's projected to hit $1.8 billion by 2020 — more than twice 2018 revenues.

- The global audience for esports is projected to grow past 450 million people this year.

Go deeper: Esports, the new social square (Axios)

Mailbox: The shaving giants

New Hampshire, circa 1950. Photo: Orlando/Three Lions/Getty

We received several reactions to Erica's story last week about shaving startups.

In a series of tweets, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers wrote:

"This article is as vivid an example as I have seen of the need for an overhaul of US antitrust. If this can be happening in shaving industry, problems may be pervasive even outside technology.

The interesting question is how much of the problem is failed enforcement of existing law and how much is that existing law needs to be altered. I suspect the former.

You do not have to have a broad new theory of antitrust to be appalled by these developments. They look terrible for consumer welfare."

And Eric Tischler of Silver Spring, Maryland, wrote: "As a former Mach III devotee, I can tell you that the six-blade Dollar Shave Club head is legit."

4. Worthy of your time

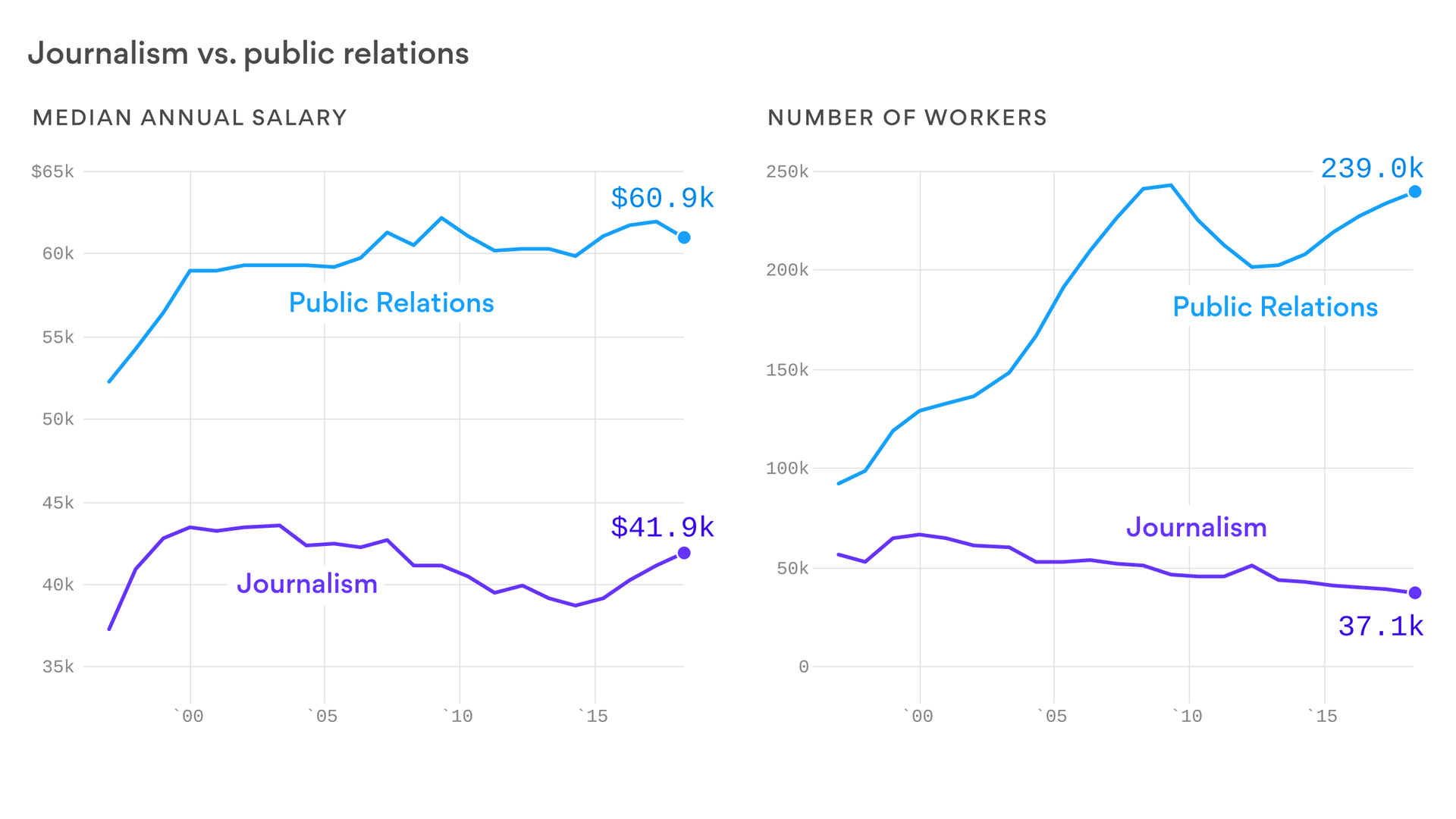

Chart: Lazaro Gamio/Axios

How to talk capitalism to millennials (Edward Glaeser — City Journal)

The ever-rising flack-to-hack ratio (Courtenay Brown — Axios)

Why Amazon bought PillPack (Christina Farr — CNBC)

A troubled coding boot camp in Appalachia (Campbell Robertson — NYT)

How did Danielle Steel write 179 books? (Samantha Leach — Glamour)

5. 1 fun thing: Falling robots

Photo: Courtesy Squishy Robotics

A new breed of small, bouncy robots are meant to rain down over disaster sites, gathering vital data from where they fall to help rescue missions in uncertain terrain.

Kaveh writes: Originally designed for a NASA mission on Titan, Saturn's largest moon, these squishy robots — designed by a Berkeley company called, well, Squishy Robotics — pack tons of sensors into the size of a softball.

- Far from the humanoid and dog-like robots of Boston Dynamics, these bots are protected by a web of cables and rods that can absorb the shock of hitting the ground after falling hundreds of feet.

- Once there, they can shimmy around and even climb over small obstacles to figure out what's going on nearby.

Go deeper: The robot that can be dropped from a helicopter (TechCrunch)

Sign up for Axios Future

Spot the mega-trends impacting our world