Axios Future

December 14, 2018

Welcome to a special edition of Future. A cottage industry of authors and artists have attempted to make sense of the chaos around us. Today, we take a look at a handful of books, a podcast and one song that stand out — most released this year, but a couple speaking from the distance of time.

I'd love to hear your thoughts. Just hit reply to this email or shoot me a message at [email protected].

Okay, let's start with ...

1 big thing: Understanding a world in upheaval

Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios

Rarely has the world witnessed so much unsettling change so fast in so many nations for so many reasons.

- A torrential decade has unleashed massive financial, political and technological crises, crises of trust, truth and untethered populations.

- People are irate and balkanized, and provocateurs, itching to make them more so, keep stirring the pot.

Never in recent memory has the danger of some imminent, undefined catastrophe felt so genuinely palpable.

The big picture: It's important to step back and think deeply about the currents running through this moment of history — and what could come next.

To begin, I chose among the most disturbing and conspicuous dynamics of the period — the extreme anger all around (most recently in France and Brazil), and, everywhere, the urge to create "others" in society.

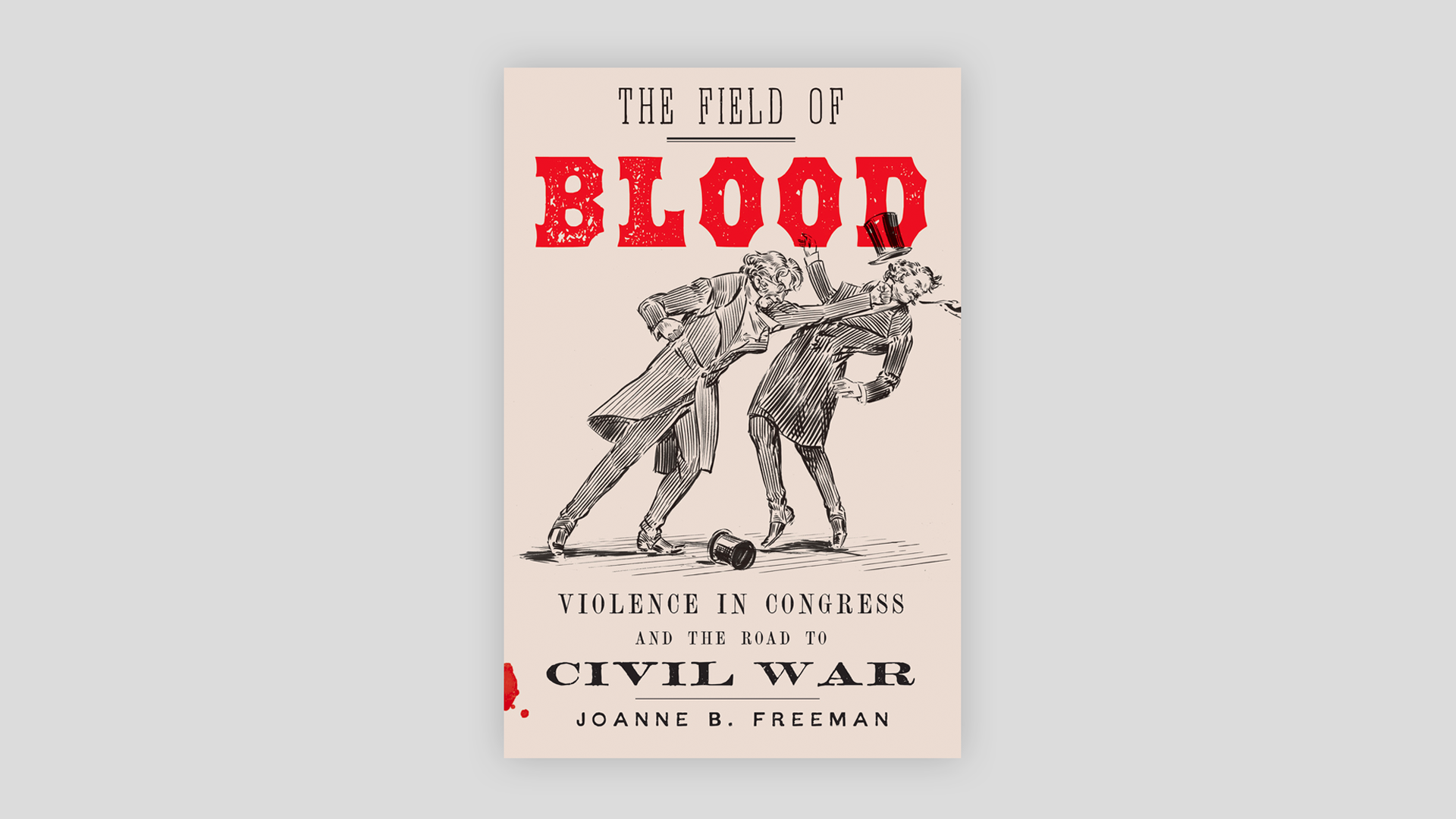

My guide was "The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War," Yale historian Joanne Freeman's exploration of the last time Americans were so divided — the decisive three decades leading up to the war that tore the U.S. apart.

The bad news: If there is a lesson in these years, it is that our circumstances can get worse. It was a time of extreme, polarized U.S. politics, strange and vicious conspiracy theories, and cutthroat media that amplified all the noise.

- Eventually, the Civil War closed in, even though “no one at the time thought it was inevitable. People were trying to protect their interests without blowing up the whole thing,” Freeman told me.

- When people worry about the divided country, that’s what they are really asking: Whether that 19th century past is in store for us — a new national conflagration, the result of never having figured out how to reconcile our differences. Are we mere tribes, seeking advantage and to hell with the other guy?

“I’m not saying we are marching into civil war. But you can see the power that conspiracy theories can have and how people can be swept into them.”— Joanne Freeman

The book's title refers to an 1856 letter written by abolitionist John Turner Sargent, calling the floor of Congress "that field of blood."

- From around 1830 on, Congress was a practice ground for the Civil War — "a den of braggarts and brawlers, a place of sectional conflict waged by sectional champions," Freeman writes. Representatives regularly punched, knifed, threatened — and once shot and killed each other.

- This was not seen as unusual — because the U.S. was an extraordinarily violent place. Voters demanded such displays of loyalty to conviction. "Nothing but denunciation and defiance seem to be tolerated by the masses," a former Northern congressman wrote. If you failed to be angry enough, you could be summarily voted out.

- They were fighting less for a moral cause than their section of the country — their tribe, in today's parlance. They felt their region's honor at stake.

Ultimately, as we know, the impulse was not honor or gallantry, but slavery. At the same time the British Empire abolished slavery (1833), there were auction blocks and slave pens right in D.C. Shackled slave gangs were marched along the capital's streets.

- In 1865, an unambiguous conclusion to the war was the only way to break the fever.

- Freeman says rightly that she's produced a window to what can happen when people become trapped in their own polarized politics and "can't see their way out."

- "As violent and strife-ridden as the nation and its politics continued to be, a new day was at hand."

Go deeper:

2. Interview: Democracy isn't the problem

Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios

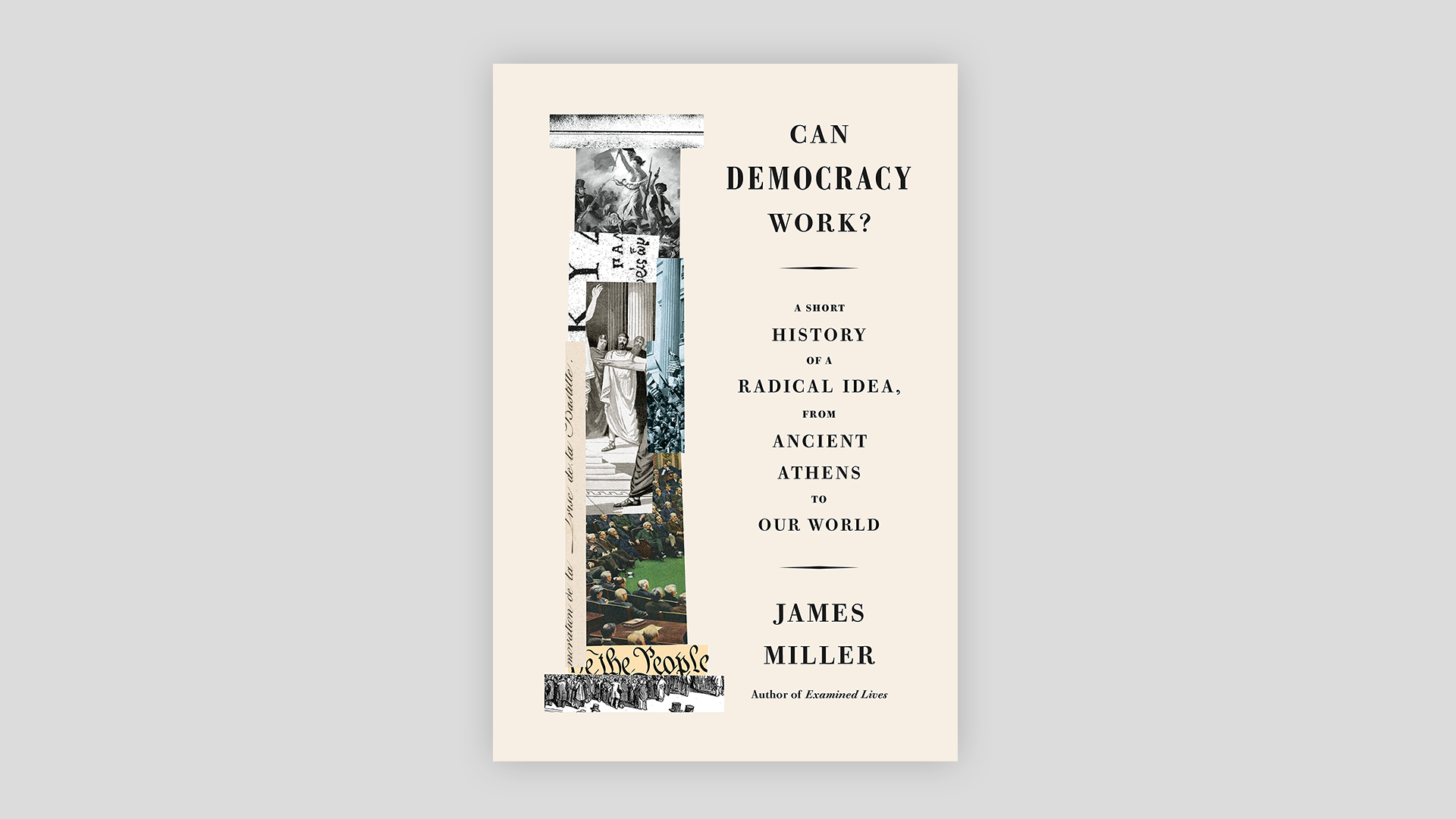

It only seems to be a time of intense challenge for democracy. Actually, we are in one of history’s most vibrant periods of people power, says James Miller, author of “Can Democracy Work: A Short History of a Radical Idea, from Ancient Athens to Our World.”

- Americans may not approve of the type of democracy being practiced in, say, Hungary and Poland. But free, fair and clear majorities elected their governments, Miller tells me.

- “The challenge to liberals is that there has been wave after wave of something abhorrent to them — these have been illiberal and anti-liberal.”

I spoke with Miller this week. Here is an edited excerpt:

Axios: You see a certain arc to the modern phase of democracy?

Yes, I see an arc that runs from the resurrection of democracy as a modern ideal in the French Revolution through to the present, where almost every existing regime claims to be a democracy of some kind (even Russia and China).

Illiberal democracy is democracy, too, right?

Simply sneering at our opponents in democratic societies, and labeling them "populists," as a pejorative term, and asserting that their preferred policies inexorably lead to authoritarianism, and show "how democracy dies," seems to me both historically inaccurate, and politically unhelpful.

How did the U.S. get here?

There was a complacency by Americans about winning the Cold War. Then [a few] blows shook the complacency — of course 2001, the financial crash in 2008. The crash was incredibly important because the assumption of liberal democratic regimes is that the meritocratic elite knows what it's doing. But they blew it and made experts look bad, like Vietnam made military experts look bad.

Are there clues as to where this period ends up?

There are good reasons to worry about what a people trying to exercise its power directly may produce. Democratic revolts can be perverse, and illiberal, in their results. So can democratic elections. I personally believe that — come what may — it is not unreasonable to uphold Lincoln's characteristically American hope, especially in the darkest of times, "that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the Earth."

Is the jury still out?

I am not super-optimistic. But the jury is still out. If you care for liberal democracy, you have to fight for it. We are not Hungary yet.

3. It started with the crash

People were unhappy about bank bailouts following the crash. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty

Back in September, Axios published a special report on the 2008 financial crash. As part of it, we asked nine U.S. economic and financial experts to name the greatest fallout. Their most frequent answer: the loss of public trust and the conspiratorial and paranoid thinking that has surged into politics since.

- Adam Tooze, author of “Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World,” agrees. When Tooze, a Columbia history professor, observes the political upheaval in the U.S. and Europe, he sees the continuing reverberations of the crash and the oblivious financial elite that was supposed to have policed the system.

Christopher Leonard, author of the forthcoming "Kochland," writes for Axios: In a scathing, 706-page autopsy, Tooze urges people to stop fretting over the possibility of another 2008. The economic crisis never really ended, he says. Instead, after smoldering for a decade, it’s now the “comprehensive political and geopolitical crisis of the post-Cold War order."

- Tooze bracingly compares the causes and impacts of 2008 with those of 1914, when European leaders sleepwalked into World War I. "There is a striking similarity between the questions we ask about 1914 and 2008,” Tooze writes.

- “How does a great moderation end? How do huge risks build up that are little understood and barely controllable? How do great tectonic shifts in the global order unload in sudden earthquakes?"

One of Tooze’s answers is that big banks are to blame. His thesis is that, when it comes to the global economy, nations matter much less than 20 or 30 intertwined financial behemoths that continue to run the show.

- In Ireland, for example, the 2008 losses of three big banks equalled 700% of the nation’s GDP. Somehow, the Irish government still decided to bail them out — “for fear of dying [Ireland] would commit suicide,” Tooze writes. This effectively bankrupted the state. The same story played out around the world to varying degrees of severity.

Tooze warns that potential calamity still lurks just around the corner, and he worries that current politics won't allow governments to do the right thing if one arises. The U.S., he says, managed to stop another Great Depression but has no long game.

Even if they don't know the details, voters can sense something is wrong. It’s no wonder that around the world they are throwing the bums out.

4. Chart: Technology has over-saturated us

For millennia, technology, in terms of its big-picture impact, was, well, meh. Look at the straight line in the chart — that includes every major invention since the year 1 AD, including the printing press. Then James Watt triggered the Industrial Revolution by reinventing the steam engine, and before you knew it we all owned iPhones.

- It's all come too fast. We are saturated with life-rattling new technologies, yet more is on its way — artificial intelligence, quantum computing, robots and greater use of cyber weapons.

- They are changing our lives in ways both good and not so much.

- In the latter category, the way we use technology is making us more distracted and divided — and allowing bad players to create chaos and tear apart our open societies.

These dizzying creations may not be boosting the economy at nearly the same scale as prior big inventions.

- In "The Rise and Fall of American Growth," published in 2016, Northwestern University economist Robert Gordon created a tizzy by blaming laggard technology invention for our relatively flat productivity growth.

- He argued that most of our genuinely impactful inventions were already with us by around 1970. That includes electricity, the airplane, air conditioning and the TV.

- Inventions since then, while impressive, simply are not of the same scale in terms of elevating overall productivity, Gordon said.

5. Geopolitics, in three spoonfuls

The Bretton Woods conference, July 1944. At the center is the economist John Maynard Keynes, one of the delegates. Photo: Hulton/Getty

Are we careening toward a new world war? And, if the old order is falling apart, what comes next? Over the year, we've asked these questions of numerous leading U.S. foreign policy hands. Below are interviews with the authors of three books with three different answers.

1. Graham Allison: "Destined for War"

Allison, a Harvard professor, says that existing and rising great powers have almost always gone to war. He calls it the "Thucydides Trap."

2. Ivo Daalder: "The Empty Throne"

Daalder, president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, argues that President Trump resembles the nationalistic and populist leaders of the 1930s. He finds other disturbing features from the 1930s as well.

3. Robert Kagan: "The Jungle Grows Back"

Kagan, a fellow at the Brookings Institution, argues that the post-World War II order is gone, and that we have reverted to "the jungle," the more dangerous, strongman-led politics that formerly dominated the world.

6. Podcast: Racism is fraying society

Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios

Race, gender and nationality are flashpoints across the U.S., Europe and elsewhere. The issues of migrants, #metoo, and the killing of unarmed black youth have been explosive, shaking up industries, elections and how our societies relate.

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, author most recently of "We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy" and writer of the Black Panther comics series, says fraught race relations are a root cause of the fraying of order in America, writes Axios' Erica Pandey.

- In February, he told podcast host Jamie Weinstein that there is little reason to expect things to get better.

- “I can’t cite a single example when people of their own volition and good-heartedness, as a group, said, ‘We’re going to willingly cede with a certain amount of power to benefit a group of people who don’t have so much because we have so much.’ I just don’t think that’s the nature of people.”

7. The last time fate surprised

Vienna coffee shop, 1890. Photo: Imagno/Contributor/Getty

"I was born in 1881 in the great and mighty empire of the Hapsburg Monarchy, but you would look for it in vain on the map today; it has vanished without a trace."

So starts "The World of Yesterday," writer Stefan Zweig's classic 1942 memoir of a time wiped out by two world wars. On the short list of books we see trotted out to understand the last two or so years, the most frequently recommended is George Orwell. Though far fewer people know of him, Zweig is also often on these must-read lists.

I recommend him, too. By way of explaining why, here is a short excerpt.

"The 19th century was honestly convinced that it was on the direct and infallible road to the best of all possible worlds. The people of the time scornfully looked down on earlier epochs with their wars, famines and revolutions as periods when mankind had not yet come of age and was insufficiently enlightened.

Now, however, it was a mere matter of decades before they finally saw an end to evil and violence, and in those days this faith in uninterrupted, inexorable progress more than in the Bible, and its gospel message seemed incontestably proven by the new miracles of science and technology that were revealed daily. ...

People no more believed in the possibility of barbaric relapses, such as wars between the nations of Europe, than they believed in ghosts and witches."

Go deeper: In 1952, British philosopher Bertrand Russell, then 80, gave this riveting 28-minute filmed interview. It spans his own life and that of his grandfather, who served in Parliament while Napoleon was on the throne.

8. 1 song-of-the-year thing: Your Twitter feed in lyrics

Screenshot: Love it if we made it

2018 is a really weird time. You can reach the utter apotheosis of pop culture, but still be mocked for being too mainstream, too safe.

And that's pretty much where The 1975's "Love It If We Made It" sits right now — a song seemingly so clinically developed for the present that it miraculously manages to transcend its own too-calculated creation.

- While it might not be playing over and over on your radio, it was rated Pitchfork's top song of the year earlier this week, guaranteeing its spot on tastemaker playlists for years to come. It tops the NYT song-of-the-year list.

Axios' Shane Savitsky writes: The easiest thing would to be call it the millennial generation's "We Didn't Start the Fire." And that wouldn't be wrong. The cadence, the energy, the relentless lyrical desperation to place it in the here and the now, that's what elevates "Love It If We Made It" from a half-hearted stab at pop grandiosity to something a bit more sublime.

- Its lyrical immediacy is its strength — precisely what's simultaneously taken Ariana Grande's "thank u, next" to similarly great heights — as it becomes a sort of year-end list all on its own.

The song is your Twitter feed brought to life, highlighting the political and societal highs and lows of recent years in pithy fashion.

- Its lyrics move from the some of the most impactful events ("'I moved on her like a bitch' / Excited to be indicted") to the smallest ("'Thank you Kanye, very cool'") to both in quick succession ("A beach of drowning three-year-olds / Rest in peace Lil Peep").

- And its chorus manages to be both uplifting and damning at the same time, depending entirely on the listener's mood ("Modernity has failed us / And I'd love it if we made it").

The bottom line: "Love It If We Made It" is a song so locked into this moment — our era of misinformation, social media, the opioid crisis — that millennials' children will either find it an incredible time capsule or a terrible joke. And that's probably exactly how The 1975 want it.

Sign up for Axios Future

Spot the mega-trends impacting our world