Axios Future

November 15, 2018

Welcome back to Future. Thanks for subscribing.

Consider inviting your friends and colleagues to sign up. And if you have any tips or thoughts on what we can do better, just hit reply to this email or shoot me a message at [email protected].

Okay, let's start with ...

1 big thing: How to fight in the heartland

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

When Amazon began its nationwide search for a place to house its second headquarters, choosing an up-and-coming city in the Midwest seemed to a lot of people like the perfect option: At a time of much scrutiny of Big Tech, Amazon would earn political points. And amid much worry about economies in the heartland, a city on the rise would get a top-notch anchor employer.

What really happened: HQ2 finalists from the heartland never had a chance.

Axios' Erica Pandey writes from Columbus, Ohio: Amid the more than 200 also-ran cities with broken hearts, there are places like Columbus — the beneficiary of giant economic strides by its own efforts over the years, but retaining the stubborn, starry-eyed hope of one day capturing one of the big fish.

- Yet experts tell Axios that a big message of the Amazon sweepstakes is that middle-size U.S. cities should look elsewhere for an economic lift.

- "The higher productivity arising from the dense concentration of very high-skill programming talent in San Francisco, New York City and D.C. cannot be matched by smaller markets such as Columbus," Joseph Gyourko, a professor at UPenn, tells Axios. "They have to be attractive on other margins, and a much lower cost of living with a good set of urban amenities is how they must do it."

- "As a country, we’d be much better if the cities were not competing to hand out checks to the biggest companies in the world," says Jay Shambaugh, director of The Hamilton Project at Brookings.

The big picture: Amazon's announcement yesterday that it would build new headquarters complexes in suburban D.C. and New York revealed a stark divide — on one side, East Coast superstar cities running away with all the talent, infrastructure and wealth, and on the other, the rest of the country.

- Despite the chasm, mid-sized cities persist in looking to a tech behemoth as an economic lifeline, experts tell Axios.

Here in the capital of Ohio, businessmen incessantly cite the cautionary tale of Wisconsin and Foxconn:

- The state promised Foxconn $4.5 billion for 13,000 jobs — about $346,000 per job.

- As a comparison, Virginia will pay Amazon about $22,000 a job for HQ2.

- The 2017 Foxconn deal is now widely seen as an exorbitant gamble.

A number of experts call Columbus a model for how a middle-size city can navigate the new economy. For two years, Harvard has hosted a course on the city, called The Columbus Way. Columbus has established startup incubators and redeveloped neighborhoods, attracting shops, restaurants, bars, theaters and art galleries — the sort of amenities that keep talent around, including graduates of Ohio State, a 66,000-student campus. The city has sought diverse businesses so as not to rely on one sector:

- Root, the city's first unicorn, is an insurance company.

- Retail chains have turned Columbus into a laboratory for the future. It is home to L Brands — owner of Victoria’s Secret, Bath & Body Works, and Lane Bryant — along with new spin-out retailers.

Jan Rivkin, the Harvard professor who teaches the course on Columbus, tells Axios that a differentiating factor for the city is the level of civic engagement.

- For example, when Columbus won a national contest for a federal smart cities grant in 2015, the government gave it $50 million, then local private companies added an additional $525 million.

- At a time when trust in leaders and institutions around the world is cratering, "the heart of what they do [in Columbus] is cross-sector collaboration, and that requires trust among sets of individuals that have quite different interests," Rivkin says.

Columbus officials say — not entirely convincingly — that they don't want to be a superstar city like San Francisco, New York or Los Angeles, but instead to dominate the second tier. One of its big promises to companies considering the city is a high quality of life in a cheap part of the country.

The bottom line: Between 2000 and 2009, Columbus added 12,500 jobs. From 2010 to the present, it has added 158,000.

- "The hardest problem is getting people on the plane" to the city, says Mark Kvamme, a former partner at Sequoia, in Silicon Valley, and now founder of Drive Capital, a venture capital firm based in Columbus. "We have an almost 100% batting average once they're here."

2. The coming dire robot shortage

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

Over the coming decade, the U.S. is going to need a lot more robots to close a yawning gap in skilled workers. But U.S. companies are investing little in automated technology, prolonging the economically debilitating effects of the skills shortage.

Axios' Kaveh Waddell writes: The skills gap in the manufacturing sector will cost the U.S. economy $2.5 trillion in the next 10 years, according to a study released today by Deloitte and The Manufacturing Institute.

- In that period, 4.6 million new manufacturing jobs will be created — but 2.4 million of them will remain unfilled because of the shortage of skilled workers.

- Nearly half of the openings will result from retirement, as baby boomers leave the workforce en masse.

The big picture: For the U.S. to stay competitive, its companies must take a page from the Chinese playbook. As we’ve reported, China is investing billions in factory robots as wages rise and labor becomes more expensive.

- "The US urgently needs a more aggressive approach to developing and adopting robotic technologies for manufacturing," according to a recent report by Boston Consulting Group and Carnegie Mellon University.

- Robots will help counteract several forces threatening to hold back U.S. manufacturing: the labor shortage, decreasing productivity, rising barriers to trade and China's swift robotization.

"I am not worried so much about the Chinese investment in robotics manufacturing as I am about the U.S. not being an active player in this field. That is the real concern. The Europeans and Chinese are ahead of us."— Howie Choset, professor of robotics at CMU and report co-author

3. Not investing in AI

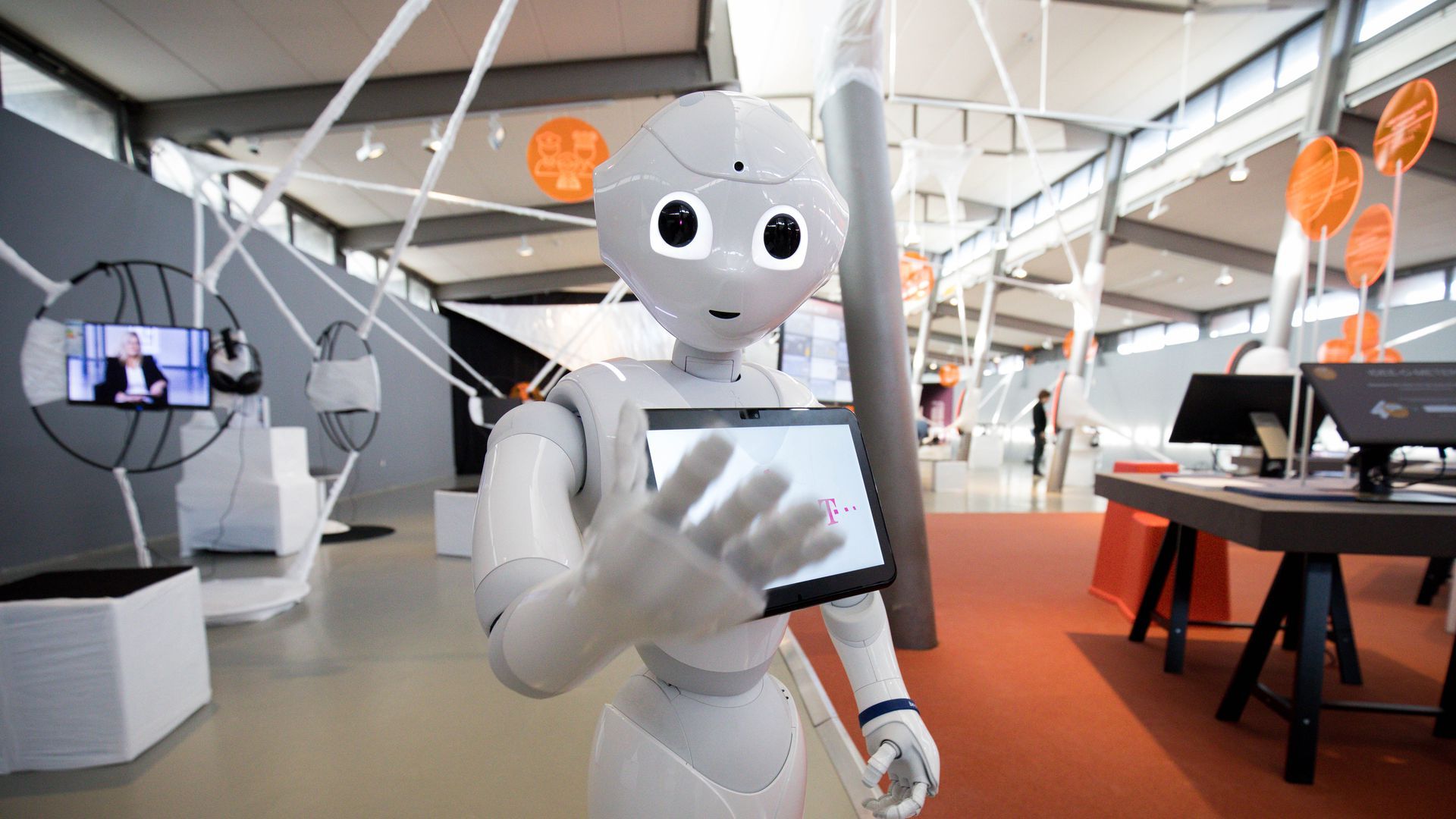

"Pepper," at the Museum der Arbeit in Hamburg, Germany. Photo: Christian Charisius/picture alliance/Getty

Most U.S. companies continue to hesitate before diving into the age of artificial intelligence, unsure precisely what they should do and afraid of making a bad investment.

Axios' Ina Fried writes: Just 3% of companies have invested enough in AI to see a significant return on investment, says Maribel Lopez of Lopez Research.

The big picture: The slow uptake doesn’t mean businesses are not interested, says Julia White, a VP in Microsoft's Azure unit.

- hey should start by gathering data, White says. If you want to use AI in your business, you need lots of information and it has to be in a common format.

- "Everyone wants to focus on the sizzle," she says. "Where’s my new bot? Well, what’s your bot going to learn from?"

Yes, but: Expectations around the AI business are often overblown. White acknowledges this, but puts the blame on other companies.

- "There was so much hype around [IBM] Watson and other things that have been disappointing," White says.

- According to Lopez Research, 89% of companies say that big cloud companies have overpromised on AI.

To help propel the reticent forward, Microsoft says it is investing in tools that help companies build their own chatbot. This morning, the company announced the purchase of XOXCO, which makes Howdy, a commercial chatbot.

Flashback: In a survey released a year ago, American business executives told MIT-Boston Consulting Group that they expect a large impact from AI. But few were actually adopting the needed technologies.

4. Worthy of your time

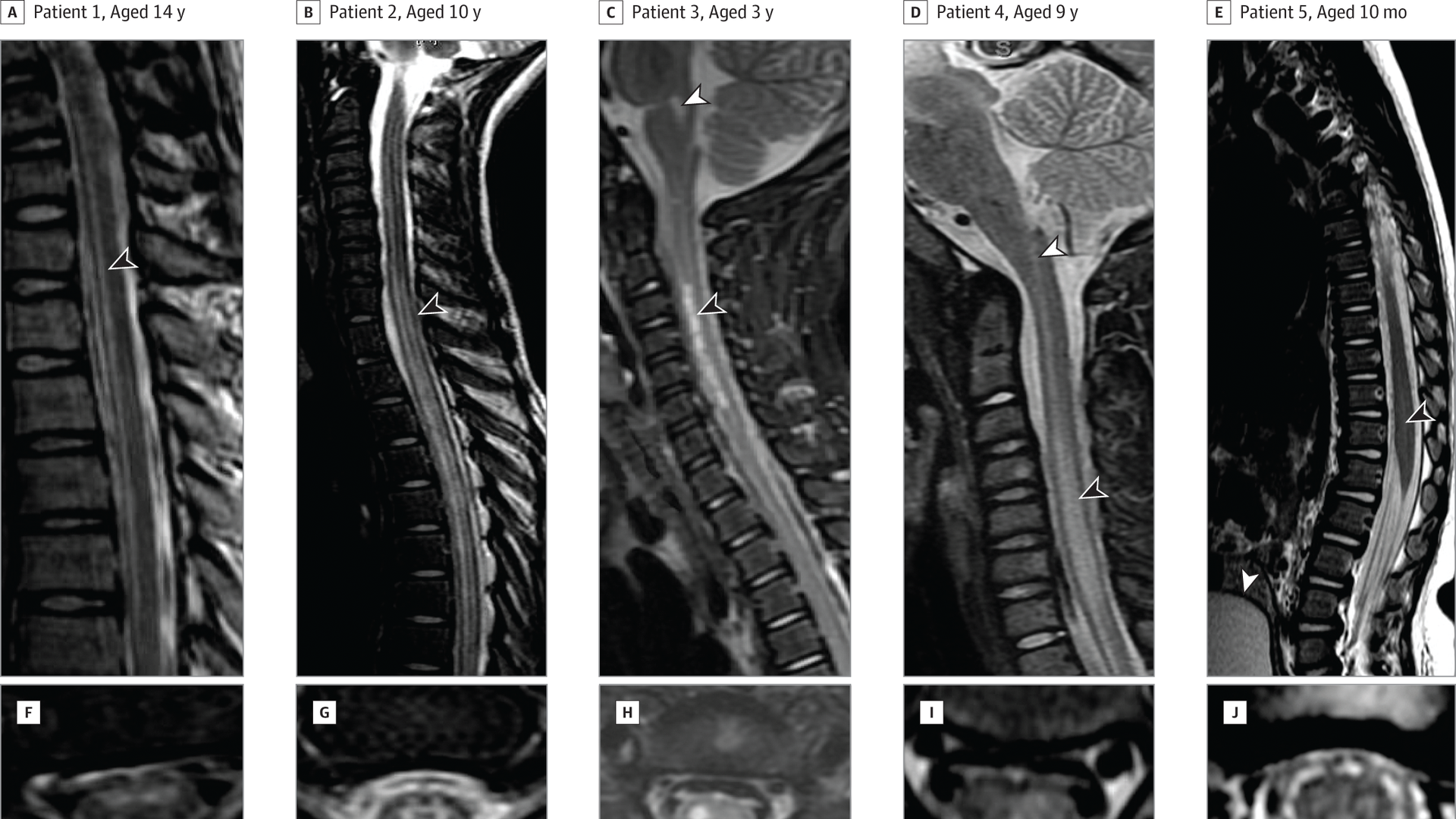

MRI of spinal cords from 5 AFM patients. Photo: Van Haren K, Ayscue P, Waubant E, et al. Acute Flaccid Myelitis of Unknown Etiology in California, 2012-2015. JAMA

Economic contraction in Germany and Japan (William Boston, Josh Zumbrun, Nina Adam — WSJ)

Rise in Polio-like illness (Eileen Drage O'Reilly — Axios)

Spiders that love light (The Economist)

Wayne Gretzky and the mysteries of greatness (Ben McGrath — New Yorker)

After the retail apocalypse, prepare for the property tax meltdown (Laura Bliss — CityLab)

1 banishing thing: Ostracism in the Twitter age

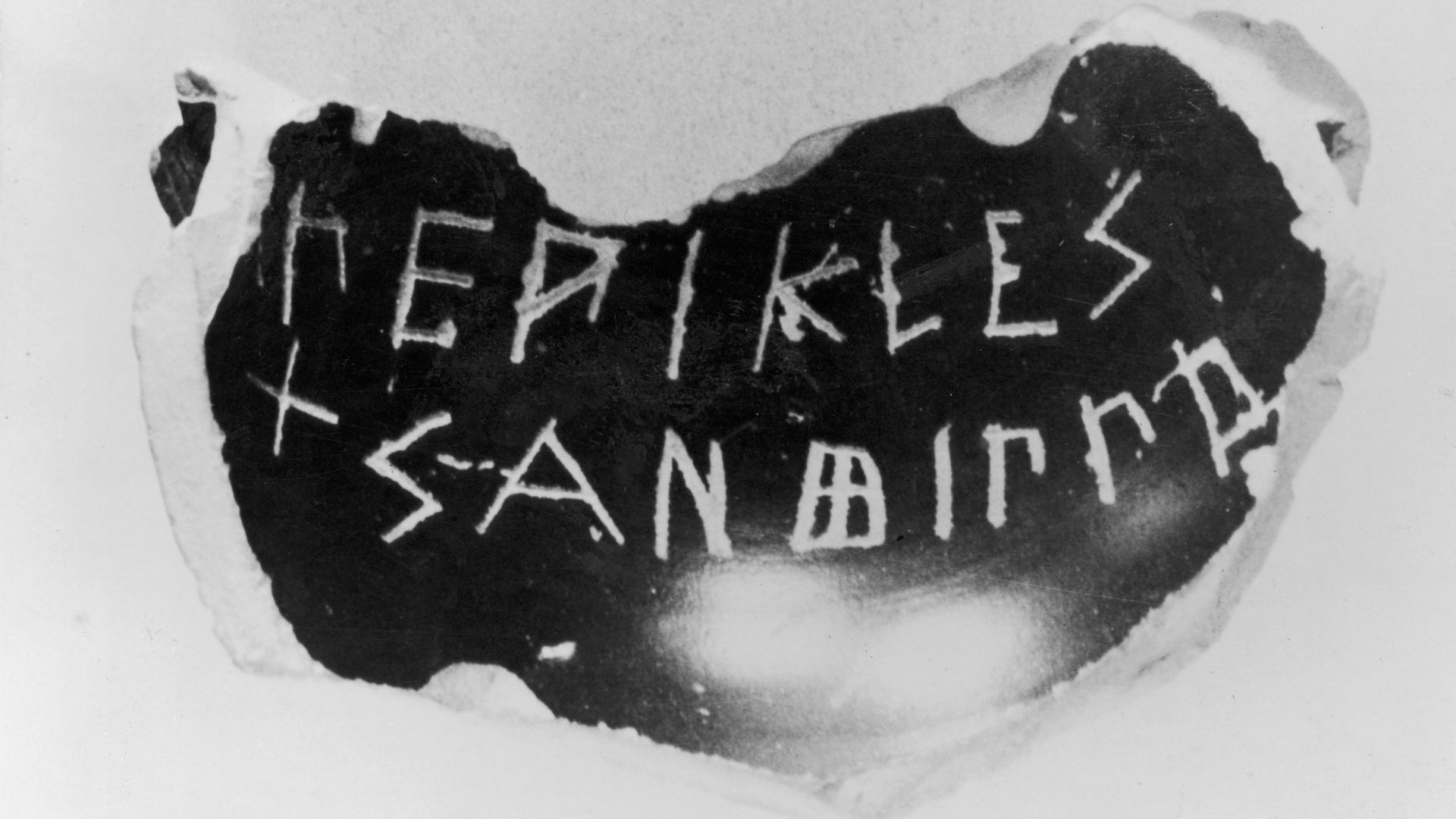

An ostracon. Photo: Mansell/LIFE/Getty

Twitter has long been criticized for doing too little to stave off racism and hate on the site, responding slowly and inconsistently to reports of abuse.

Perhaps the solution is not some AI-enabled moderation technology, but rather a process invented 2,500 years ago.

Kaveh writes: Ostracism was introduced as a democratic reform in Athens around 500 B.C. Under the system, citizens voted for a person to be ostracized by etching a name onto a pottery shard called an ostracon — like the one above, which bears the name Pericles.

- If enough people put in names, the person with the most votes would be ostracized.

- That person would be banished for 10 years but would keep his property and civil rights.

A tongue-in-cheek proposal from Joel Christensen, a classics professor at Brandeis University, would update ostracism for the 21st century information firehose.

- If a critical mass of Twitter users vote to ostracize a person, they would be banned from the site for 10 days.

- Every successive exile would increase the ban by 10 days. At 100 days, a person would be banned for life.

The bottom line: "An exile from Twitter need not be considered a bad thing," tweeted Christensen. "Some people might take if as a badge of honor. Just think of the company you’d join: Themistocles, Cimon, and Aristedes."

Sign up for Axios Future

Spot the mega-trends impacting our world