Axios AM Deep Dive

May 16, 2020

Good afternoon, and welcome to our latest Axios Deep Dive on the coronavirus pandemic and its impact on the nation.

🎂 Happy birthday to Florence Nightingale, who was born May 12, 1820; her birthday marks the end of annual National Nurses Week.

- Today's Smart Brevity™ count: 1,948 words, or about 7.5 minutes.

1 big thing: The front lines are now explosive and overwhelming

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

In this special issue, my Axios colleagues dig into the trials and heroics of America's front-line health care workers.

I got the idea for this Deep Dive when I saw doctors and nurses — for the first time in any crisis — telling their own stories, in real time, with social posts, on cable TV, and even with essays, op-eds and online diaries.

- I found these accounts captivating, informative and moving. I kept telling friends about them — always a sign you should do a story.

- The most memorable single image for me: Resourceful, compassionate nurses are using borrowed iPads to set up FaceTime conversations for dying relatives to talk to families who aren't allowed to visit.

I realized that front-line health care professionals usually escape our attention, and certainly our acclaim, until we have a forced personal encounter: a scary symptom ... a life-changing diagnosis ... an accident in the family. Doctors and nurses are suddenly the most important people in our life. We thank them, take them donuts, pray for them. And then, if we're lucky, we move on.

- Now, during this once-in-a-century global calamity, society is finally and unanimously recognizing them as heroes, with the spontaneous shows of gratitude that greeted America's soldiers after 9/11.

Why they matter ... Caitlin Owens, in a takeover issue last month of our health care newsletter, Axios Vitals, framed the medical professionals' valor:

- These workers, with loved ones of their own, keep showing up at hospitals across the country, knowing that more Americans than they can possibly care for are depending on them.

- And they've left the relative safety of their hometowns to fly into New York to help overwhelmed colleagues.

MSNBC's Rachel Maddow has played a parade of videos of nurses just talking into their phones — often in their cars, before or after a shift — pleading with people to stay home and avoid becoming one of their patients.

- An unforgettable clip came from Waterloo Community Television, and Dr. Sharon Duclos, co-medical director of Peoples Community Health Clinic in Waterloo, Iowa:

My biggest fear — as I encourage my staff to come to work every day, and be compassionate and help people — ... is I'm going to lose one of them. And then I have to carry [that] on my shoulders, because I'm asking them to do a service that I realize is very hard...

I know they've got that pit in the middle of their stomach. And you get up and you come to work, and you think: "OK, is this the day?"

So please, work on the social distancing, please help people out, so the number of deaths that we have to endure are minimized as much as they can. That's my plea today. Thank you.

Thank YOU, Sharon — and all the Sharons across our sad land.

- 🎥 Video: Watch an interview with Dr. Duclos, including her care for a patient who had been laid off "and doesn't understand why this has to happen."

Sign up for Caitlin's Axios Vitals.

Bonus: Pic du jour

President Trump poses with nurse Amy Ford during a Rose Garden ceremony at the White House yesterday. Photo: Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images

West Virginia nurse Amy Ford traveled to Brooklyn at the start of the pandemic to help treat coronavirus patients. She was honored yesterday at the White House.

I had to adapt to a new way of nursing — one where treatment was still unknown; one where families had to trust my word, and I had to prove that my word was trustworthy; one where I could only provide comfort by holding my patient's hand because I could no longer give comfort with numbers and statistics of success rates. Those were unavailable in the beginning.

I provided families comfort through FaceTime calls — holding my phone up to a patient's ear, hoping that, by hearing their loved one's voice, it would in turn give them comfort as well.

This experience has been one of the most emotionally challenging things that I've ever been through, but it has made me a better person in the end.

2. Worst case fears avoided (for now)

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

In March and April, as the scope of the pandemic became known, there were dire warnings of a health care system crushed under the burden, driven by stories of overloaded hospitals in Italy as the pandemic peaked.

- The most dire crisis was avoided. Ventilator shortages never materialized, hospital ships dispatched to New York City and Los Angeles were little needed, and health care providers didn't face the most harrowing life-or death scenarios all of the time.

Why it matters: As states begin to experiment with reopening, there are chances virus hotspots could return, making it worthwhile to remember these past challenges.

Case in point: Projected shortages of ventilators had led health care workers and hospitals to plan for sharing ventilators, converting anesthesia machines, or even making in-the-moment decisions on which patients would get access to ventilators and which wouldn't.

- In Italy, the situation had deteriorated to the point where doctors were advised to prioritize younger, healthier patients, per Politico.

- One New York hospital subsequently told ER doctors in March they'd have "sole discretion" to place patients on ventilators, and that the hospital supports withholding "futile intubations," the Wall Street Journal reported.

- Flashback: In early April New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio had warned that ventilator shortages were days away.

The bottom line: Social distancing measures and stay-at-home orders helped avoid the worst in the initial phase of the outbreak.

- But there is still no treatment to stop the progression of the disease, and the many unknowns will continue to make health care workers’ jobs difficult and stressful.

Go deeper: Where coronavirus hospitalizations are rising and falling

3. Health care jobs not immune to losses

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

The coronavirus pandemic is a health care crisis, but health care still isn't immune from the rampant job losses the pandemic has wrought, Axios' Bob Herman reports.

By the numbers: The health care industry lost more than 1.4 million jobs in April.

The reason: These jobs have gone away because outpatient care has dried up, as providers postponed elective procedures.

- More than four out of five of those lost jobs were at offices for dentists, physicians, chiropractors and other outpatient settings.

- Technicians, billing clerks and medical assistants who work in outpatient settings — many of whom are not highly paid — have felt the brunt of the job losses.

What's next: Don't expect a quick return, even as elective procedures are able to come back online.

- "Of all the places people want to come back to quickly, a health care setting is probably not at the top of the list," said Ani Turner, a health economist at Altarum.

Go deeper: Health care's hiring boom may not help the coronavirus outbreak, since most new jobs are administrative.

Bonus chart: The grim toll

4. Worthy of your time

Hashem Zikry had been working as a doctor for nine months.

- "He is twenty-nine years old, an intern in the emergency-medicine residency program at Mount Sinai Hospital. ... In late February, he began a six-week rotation in the E.R. at Elmhurst Hospital..." Rivka Galchen writes in the New Yorker.

Why it matters: At Elmhurst Dr. Zikry finds himself in the middle of a neighborhood with a large working-class population that was "hit earlier and harder by the pandemic than most of the rest of the city."

The tale vividly illustrates preparations for a deluge of patients, the struggles in treating patients who must be isolated from their families, and the relentless toll the virus can quickly exact.

When Zikry came on shift on the evening of March 21st, one of the COVID patients signed out to his team seemed not as sick as some of the others he’d seen. “He walked by the desk during sign-out,” Zikry told me. “He walked by again fifteen minutes later. Asked us where the bathroom was. He was walking — that’s a great sign. Talking — that’s a great sign. These are very reassuring things to a physician. I wrote down, ‘Ambulatory, Conversant.’”

A short time later, a hospital police officer approached Zikry to say that a man had collapsed in the bathroom. When Zikry reached him, the man had no pulse. He began chest compressions. “Nothing like this had ever happened to me,” Zikry said. “I had seen him walking minutes before.”

The man was taken on a stretcher to the critical-care area, where resuscitation equipment was on hand. Despite the efforts of Zikry and others, the patient died about fifteen minutes later. Zikry recalled turning back toward the rest of the E.R. He said, “We look back on this sea of, like, three hundred people that expected us to treat them immediately, to figure out what was wrong with them.” This was around 3:15 a.m.

Go deeper: A new doctor faces the coronavirus in Queens (The New Yorker has made all its coronavirus coverage free.)

5. The mental health strain

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

It could be the pandemic's second curve in need of flattening — rising incidents of mental health issues or even post-traumatic stress disorder, among health care workers helping fight coronavirus.

- "New surveys of doctors and nurses in China, Italy, and the United States suggest they are experiencing a plethora of mental health problems as COVID-19 continues its spread, including higher rates of stress, anxiety, depression, and insomnia," according to Science magazine.

Why it matters: Even before the pandemic, physicians had a rate of suicide twice as high as the general population.

- During the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong, 89% of health care workers reported negative psychological effects, and 72% of Chinese health care workers surveyed during this pandemic said they had experienced "symptoms of distress," Science reported.

Two examples of the toll in New York City:

- The director of the emergency department at NewYork-Presbyterian Allen Hospital, Dr. Lorna M. Breen, died by suicide. “She tried to do her job, and it killed her,” her father told the NYT.

- A 23-year old emergency medical technician, John Mondello, died by suicide after talking to a friend about "experiencing a lot of anxiety witnessing a lot of death," the New York Post reported.

Our thought bubble: Health care workers care and comfort us through this crisis, and in the long tail of its impact they'll likely need support, too.

Go deeper: The coming coronavirus mental health crisis

6. The forgotten front line

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

The coronavirus has made life even more difficult for the 5 million aides and workers who care for the frail populations living at home and in nursing homes, Bob reports.

Why it matters: These low-paid workers face the conundrum of seeing patients and increasing risk of exposure and spread, or staying away at the expense of their income and patients who rely on that care.

By the numbers: Home health workers, nursing home assistants and other therapists and orderlies hover around poverty and are predominantly women and people of color, according to PHI, a research group that studies this group of care workers.

The big picture: It is almost impossible for workers to bathe, feed and otherwise care for their patients while social distancing, and a reliable source of masks or other protective gear for them is not guaranteed.

- That makes their already-high-risk job even more high-risk for them, as well as their patients who are most likely to die from contracting COVID-19.

- If they, their clients or the facilities decide to hold off on services, they lose what little income they have.

The bottom line: "There's no doubt that we're being sort of forgotten in all this, and I fear that mentality is going to eventually come back and punish us," Joe Russell, executive director of the Ohio Council for Home Care and Hospice, told the Washington Post.

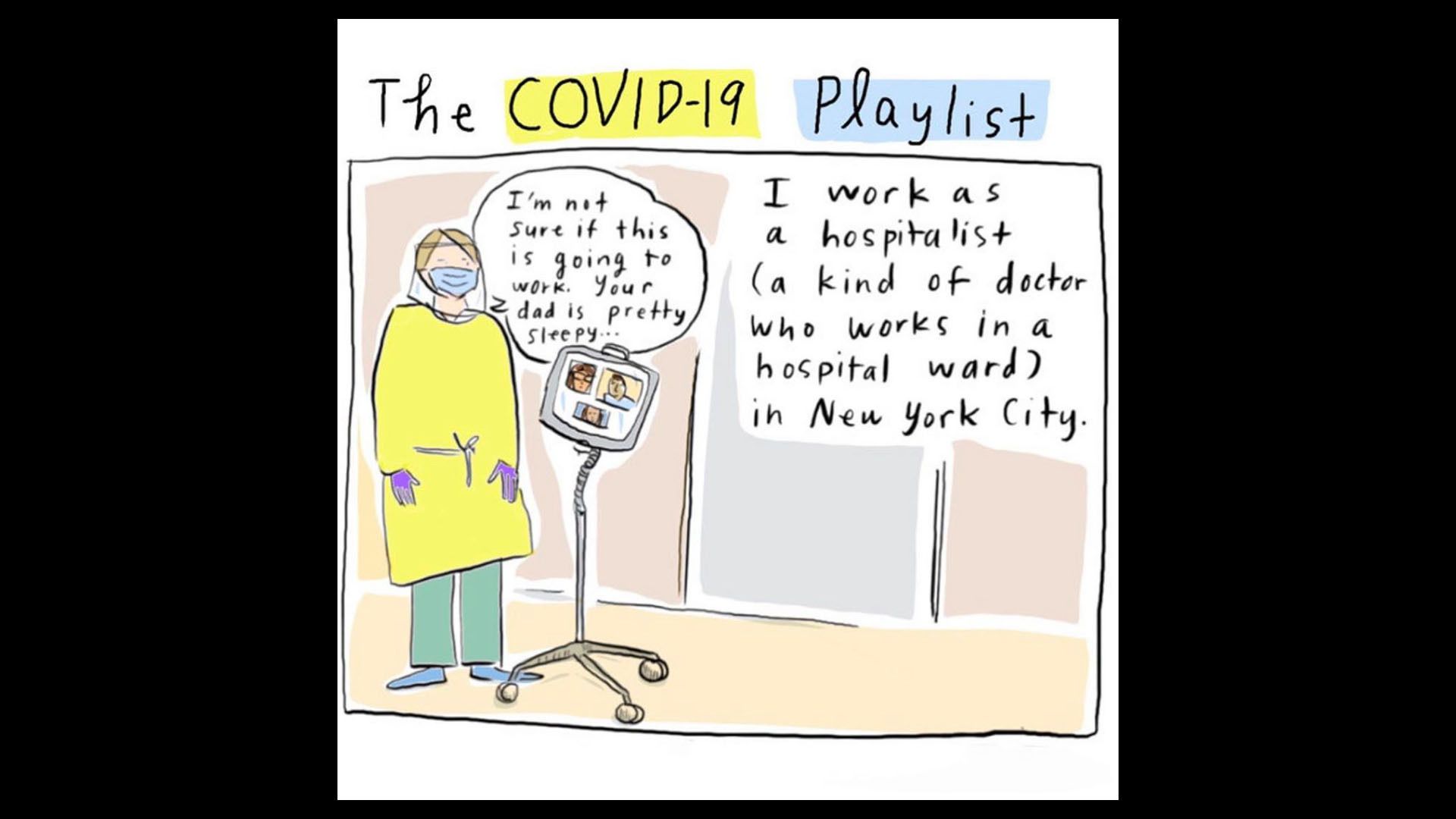

7. Art by doctors: A glimpse of the front lines

The first panel of "The COVID-19 Playlist" comic. Courtesy of Dr. Grace Farris

Art made by health care workers offers a rare look — through very personal lenses — at how the fight against coronavirus is unfolding in hospitals.

Why it matters: These can be the best glimpses of what happens behind hospital doors because patient privacy issues make it difficult for journalists to capture what is happening on the front lines.

What they're saying: Dr. Grace Farris, a hospitalist at Mount Sinai and a cartoonist, published a comic on NPR's site showing how hospitals are using music to "sing patients home" when they were discharged.

- "I have gotten a lot of messages from people saying that they loved this idea that they're playing songs," Dr. Farris tells Axios' Naomi Shavin.

- Dr. Shirlene Obuobi, also a cartoonist, says, "I do have a viewpoint that is different and valuable right now and I want people to see this from a human perspective and not from a statistics perspective."

The bottom line: Images and stories shared by these doctors, plus others like Dr. Sophie Chung, Dr. Mike Natter and Dr. Nathan Gray, help make visible the work they are doing.

Sign up for Axios AM Deep Dive

A deeper look at the biggest topics impacting the future