Axios Cities

November 13, 2019

Happy Wednesday and thanks for subscribing. Tell your friends to sign up here.

- I always welcome your feedback and ideas. Just hit reply.

- Today's edition is 1,407 words, a 5-minute read.

1 big thing: Speed bumps for smart cities

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

The journey to smart cities is off to a slower start than predicted, with many projects stuck in the pilot phase and cities unable to find the skilled workers to keep them going.

Why it matters: The vision of smart cities is to use data, sensors and software applications to allow cities to be more responsive to residents' needs (like detecting when trash cans are full) and more environmentally sustainable (like detecting water leaks in underground pipes).

The hurdles to municipal adoption of these technologies — often referred to as the “internet of things” (IoT) — were a topic of conversation at the Internet of Things Consortium conference in New York on Tuesday. Here’s what’s slowing it down.

1. Pilot purgatory

- Most cities wade into smart-city applications slowly with “proof of concept” trials to test out a technology before signing a longer term contract.

- But those pilot project phases are getting longer across the board, per 451 Research, leading to a state of limbo that IoT firms call “pilot purgatory.”

- Pilot projects are useful for getting a project or idea off the ground, says Beverly Rider, Hitachi’s chief commercial officer. “But there’s rarely a plan for what happens when the trial phase is over.”

2. Data silos

- "A city isn’t one entity, it’s a collection of agencies working autonomously,” said Samir Saini, former chief information officer for New York City.

- Big-city governments, in particular, are prone to communication breakdowns between departments. When data isn’t shared between agencies, efficiencies are lost.

3. Security fears

- Data security concerns are still the top hurdle to the adoption of initiatives involving connected devices and of getting public buy-in for projects that involve data collection, per 451 Research.

- According to research released this week by Parks Associates, 63% of the general public are concerned about cybersecurity, and 71% of people with smart devices are concerned about cybersecurity.

4. Worker shortage

- City governments have a hard time attracting workers with data science and back-end technology skills because they’re competing for that talent with big tech firms that pay much more.

- New York City faces a perennial staff shortage for smart-city projects. “After a company installs the thing, workers need to maintain it,” said Commissioner Gregg Bishop of NYC’s Department of Small Business Services.

The big picture: Adoption will accelerate as cities replace or upgrade aging critical infrastructure, such as bridges, with sensors embedded into the construction, Saini said.

- Sensors and energy-management technologies in buildings are likely to become more common as cities adopt aggressive emission-reduction goals.

2. In Seattle, a focused approach to housing

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

Senior director of Microsoft Philanthropies Jane Broom told Axios in an interview that "the probability is high" that the software giant will invest more in housing in its backyard, following its initial $500 million pledge announced in January.

“The No. 1 thing we want to do is create or preserve more housing. But I think what we’re realizing that our greater impact may be creating on-ramps or tangible new vehicles for other companies to figure out how to play in this space. It may be through investment capital, philanthropic capital or advocacy.”— Jane Broom

In Seattle, the business community has focused on targeted projects, including Microsoft's commitment and homeless initiatives from Amazon, Starbucks and tech billionaire Paul Allen.

- Seattle residents have been more open than Silicon Valley to zoning changes for more density.

- "There was a period of transition with a more project-based focus," said Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan, who is assembling a regional plan to address housing for Seattle and the surrounding communities.

- "We have to go big as a region, and we won't be able to get there without the strong help and support from the tech industry and other businesses, and state and local governments working together," Durkan told Axios.

How it works: Government tools make low-income housing possible for certain income brackets. Middle-income housing — needed by teachers, nurses and public safety workers — is much harder to finance because there are no government or tax incentives at that level, and developers can't make money on the projects.

- That's where Microsoft is trying to use its own balance sheet to design loans at below-market interest rates (around 1%).

- In September, Microsoft announced a $245 million investment to preserve 1,029 affordable rental housing units. This package comes in the form of a $60 million loan to King County Housing Authority, combined with $20 million in low-interest debt provided by King County, and $140 million in bonds issued by the housing authority.

3. Where low-wage workers are being left behind

Today's low-wage workers are concentrated in southern and western states, are disproportionately female, and are often locked out of moving up economically because they can't afford to live in cities that offer better-paying jobs.

Why it matters: Low-wage and entry-level workers are more likely to be negatively affected by automation in the workforce and less equipped to weather an economic downturn.

What's happening: The share of low-wage workers varies widely between cities, according to a new Brookings Institution analysis of data from across 373 U.S. metro areas.

High concentrations of low-wage earners are in the South and West.

- In Las Cruces, New Mexico, and Jacksonville, North Carolina, low-wage workers make up 62% of the workforce.

- In these places — like Yuma, Arizona, (57%) and McAllen, Texas, (56%) — low-wage workers tend to be Latino or Hispanic, caring for children and less educated.

Low-wage earners are less concentrated in the mid-Atlantic, Northeast and Midwest.

- California-Lexington Park, Maryland, had the lowest share with 30%, followed by Rochester, Minnesota (31%); Bismarck, North Dakota (32%); and Hartford, Connecticut (32%).

- In these places, low-wage workers tend to be white and are more likely to have a high school diploma or some post-high school education.

Yes, but: "Even in the most productive regional economies like San Jose, there are still millions of people who are struggling," said Martha Ross, a fellow at Brookings' Metropolitan Policy Program.

- "We can't just look at 'left-behind' regions versus 'superstar' regions. There are plenty of left-behind people in superstar regions," Ross said.

Middle-wage jobs used to be the bedrock of upward mobility, allowing someone with a high school diploma and some training to get a job that paid enough to support a family. But those middle-wage jobs are evaporating.

The bottom line: Jobs and place are intrinsically linked. Education is often touted as the way to help people find better-paying jobs, but more training won't lead to higher-paying jobs if such jobs don't exist.

4. Uber CEO: More cars "not the answer"

Photo Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios. Photo by Philip Pacheco/AFP via Getty Images

In an interview last week with "Axios on HBO," Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi says its business has to "radically shift how it grows" to avoid wearing out its welcome in cities.

Why it matters: That means investing in fleet electrification and convincing people to take alternative modes of transportation (like Uber buses, electric bikes and scooters) are the key goals for the company — which doesn't have a history of playing nice with cities.

"We are guests on the streets of the cities in which we operate. And we have to make sure that our growth is always in concert with the regulators, etc. ... More cars is not the answer."— Dara Khosrowshahi

The big picture: In many places, Uber is the face of the gig economy and all the baggage that comes along with it — like tensions around driver pay, lack of benefits for workers and, in terms of transportation, increased congestion.

What's next: Uber wants to be the "operating system for your everyday life, any way you want to get around or anything that you want delivered to you," said Khosrowshahi.

- Uber Eats is a model that will expand to grocery and other items like medicine. Even taking the subway (though that won't make money for Uber) may be part of that network.

Reality check: Uber essentially wants to be a platform for moving around your city. But it's becoming a tougher time to be a massive platform company as the anti-Big Tech climate persists.

5. Urban links

Illustration: Sarah Grillo

The physical footprint of the digital world☝️(Axios)

Venice floods: Climate change behind highest tide in 50 years, says mayor (BBC)

How cities and states can stop the incentive madness (CityLab)

Essex Crossing is the Anti-Hudson Yards (NYT)

Utilities accelerate AI use to drive efficiencies, profits (Utility Dive)

Quoted:

“Mayor Bloomberg did some incredibly creative things in New York City. ... But I don’t know that he could ever be the nominee of the Democratic party. I think somebody like Mayor Pete represents the call for the next generation of leadership, and I think that he would garner greater excitement and intensity. But I have a lot of respect for Mayor Bloomberg.”— Austin, Texas, Mayor Steve Adler on Texas Monthly's podcast

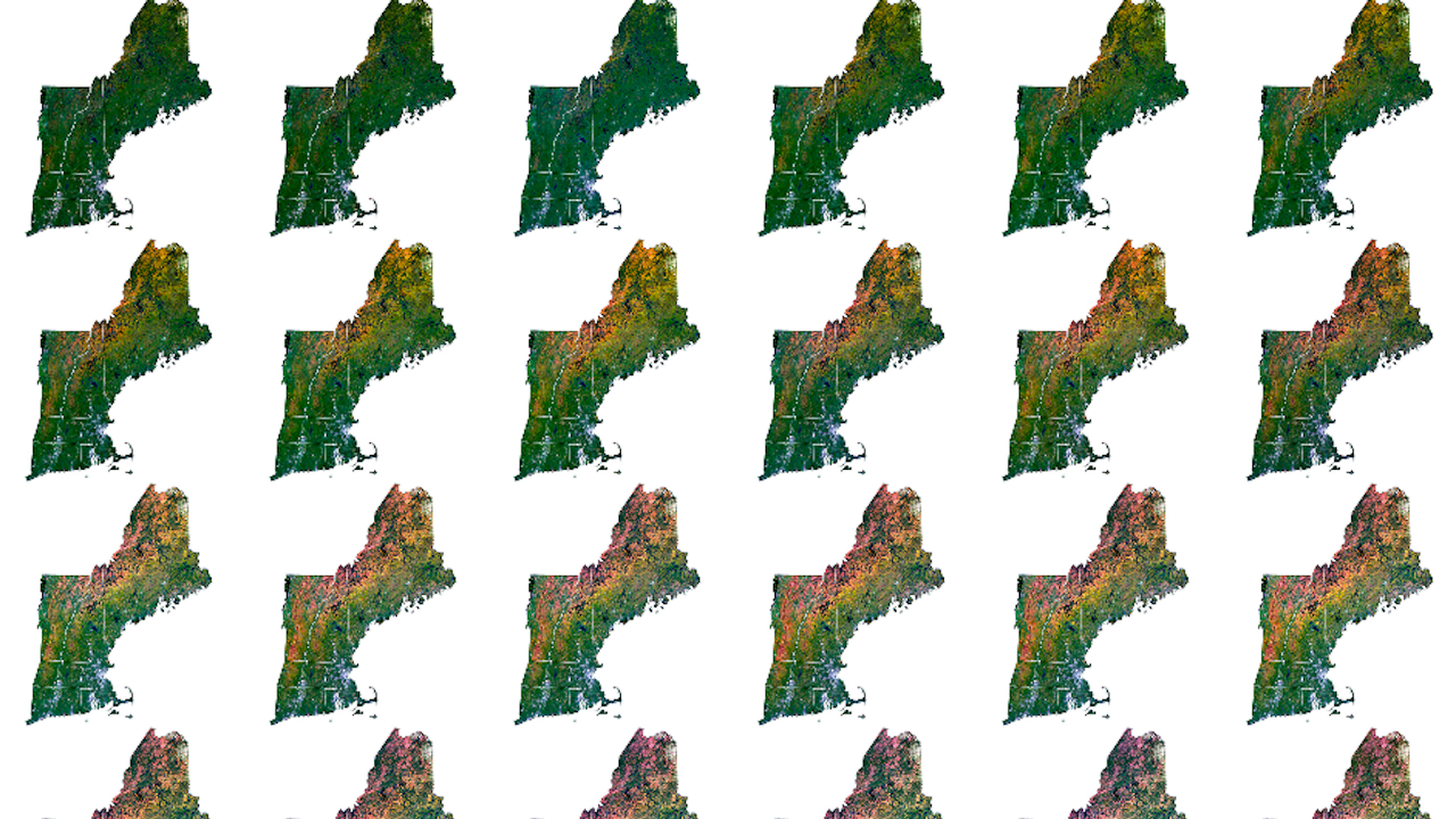

6. 1 🍂 thing: Peak fall

Satellite images of changing fall foliage in the northeastern U.S. Photo: Screen shot by Descartes Labs

Using its database of satellite images, Descartes Labs captured the progressing fall foliage in the northeastern U.S.

News you can use: Do you rake leaves every fall? Environmental experts want you to stop.

“It’s good to leave as much leaf litter on the land as possible. Leaves fall, and the nutrients from those leaves feed the plants."— Jon Traunfeld, director of the Home & Garden Information Center at the University of Maryland College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, told the Baltimore Sun

Have a great week!

Sign up for Axios Cities

Explore the technology and market forces shaping our cities