Fragments of data about a coronavirus drug don't tell us much

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

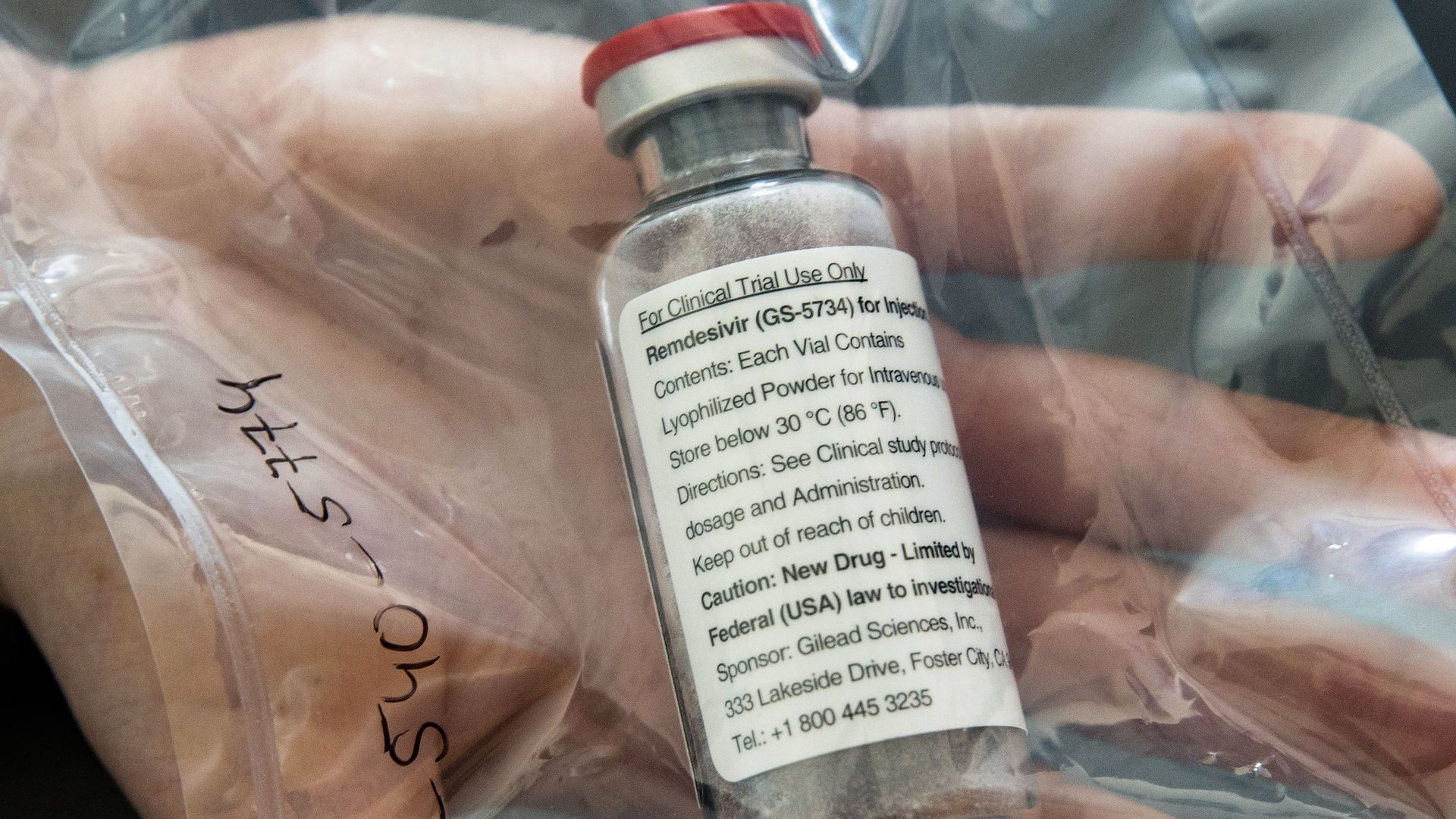

We still don't know the true effectiveness of remdesivir. Photo: Ulrich Perrey/AFP via Getty Images

Depending on the study, remdesivir is either a clinical failure or a godsend for treating the novel coronavirus.

The big picture: The grim reality of the coronavirus pandemic has the world itching to know which experimental treatments actually work, but we're not necessarily getting any smarter from these incremental drips of incomplete information.

Driving the news: Remdesivir — an antiviral drug that some experts have seen as a promising coronavirus treatment — "was not associated with clinical or virological benefits" for coronavirus patients, according to a summary of a clinical trial in China, viewed by STAT and the Financial Times.

- This comes after a separate leaked remdesivir trial at the University of Chicago suggested the opposite.

Between the lines: The truth is, we still don't really know how effective the drug is in fighting this virus.

- The Chinese trial has a randomized control group, so it is by far the most reliable study. However, the trial has not gone through peer review, and Gilead said the results were "inconclusive" because the trial had to be terminated early.

- The University of Chicago study and a Gilead-sponsored compassionate use study, which prompted rosier views of the drug, are riddled with flaws that make them hard to rely on. The most obvious drawback in both is the lack of a control group.

The bottom line: Science is slow for a reason, and the deluge of poorly designed trials and early drafts of studies is sowing confusion instead of creating clarity.

- "The world is, unfortunately, getting a crash course in the value of evidence-based medicine vs. anecdote," veteran pharmaceutical analyst Brian Skorney tweeted.

What's next: A more rigorous report from Gilead's Chinese trial is expected at the end of this month, and data from other trials is expected in late May. Don't jump to any firm conclusions before that happens.

Go deeper: The high stakes of low scientific standards