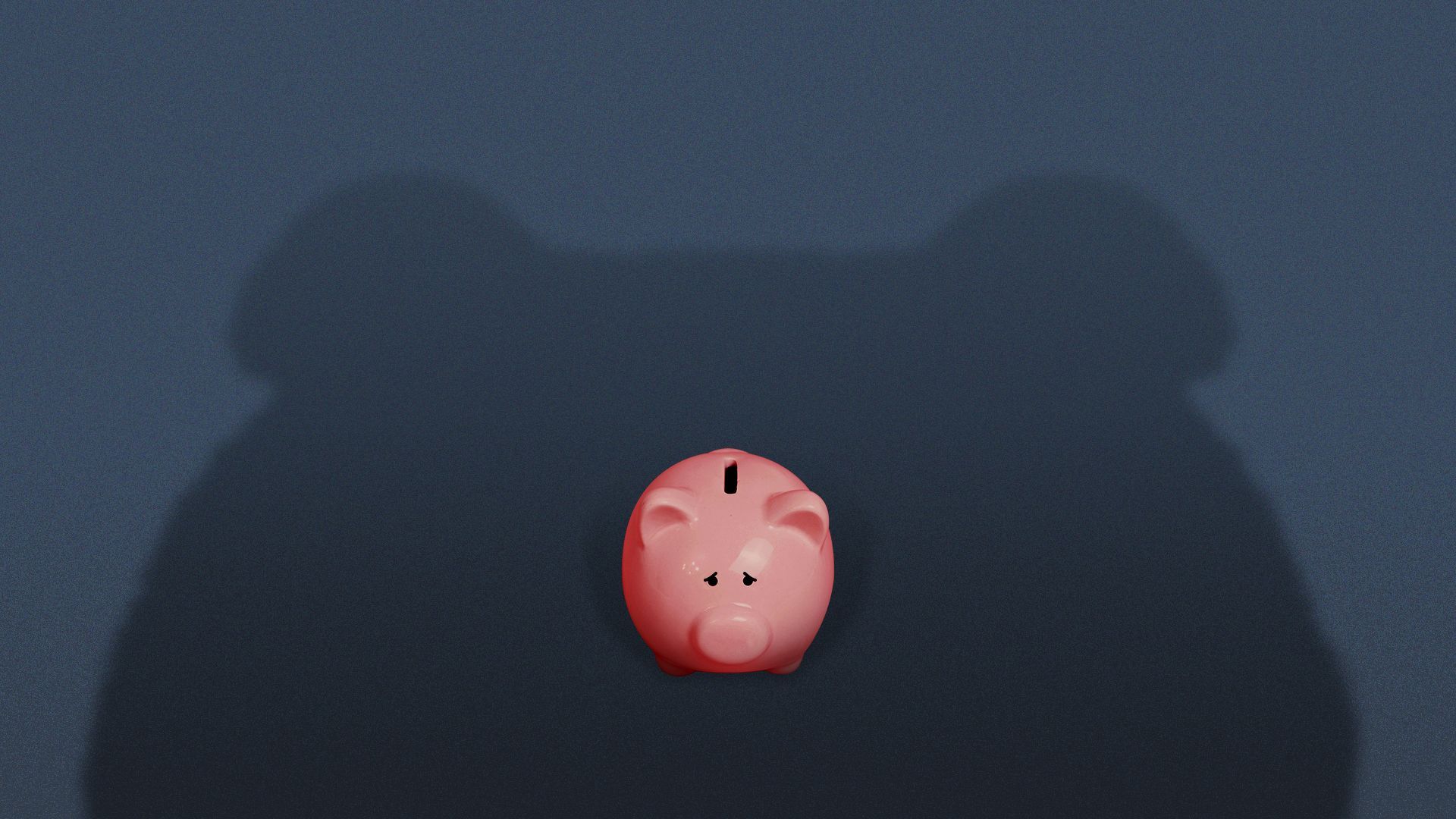

Banks fight the stock market

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

Illustration: Allie Carl/Axios

Stock prices are more germane than ever — a powerful phenomenon that is contributing to the current mini banking crisis.

Why it matters: The pandemic created a whole new generation of stock traders. Even if they're not actively playing the ups and downs of PacWest Bancorp, the country is just much more aware than ever before of what individual stocks are doing. That's bad news for banks.

Between the lines: There's a case to be made that if Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic Bank hadn't had publicly listed stock, neither of them would have failed.

- In both cases, the proximate cause of death was a plunging share price that eroded confidence in the bank, so much that it could no longer survive.

The big picture: Stock market investing can be split into generational eras.

- Boomers generally bought stocks only once they were rich; a pension plan sufficed for the majority of the generation. For this generation, investing was largely an expensive and somewhat mysterious upper-middle-class hobby.

- Generation X didn't have as much wealth as the boomers, and even if they caught the stock investing bug, they learned their lesson during the 2000 stock market crash. That helped us embrace the passive-investing revolution: We're the slacker adopters of index funds.

- Millennials had even less wealth than Gen X — until the pandemic hit. At that point, armed with boredom and stimulus checks, they started buying individual stocks — and making real money as the market soared. As ever, the higher the risk the higher the reward, so attention ended up focused on the biggest movers.

Where it stands: Some companies ("meme stocks") have become as famous for their share price as they are for their products.

- A substantial cohort of "buy the dip" investors pays special attention to shares that fall sharply — currently, that would be the regional banks — hoping they will revert back to historical levels.

Be smart: At most companies, having a lot of people transfixed by your plunging share price might be embarrassing. At banks, especially now, it can become an existential risk.

How it works: Thanks to fractional-reserve banking, a bank's market capitalization is always a small portion of its total assets. A big bank like Truist, for example, has assets of $546 billion, and a market value of $38 billion as of Friday.

- Assuming the bank trades at exactly book value, a 1% drop in the value of the assets would mean a 15% fall in the share price. A second 1% drop in assets would mean an 18% fall. And so on. As the stock falls, relatively small moves in the perceived value of the asset base can cause highly alarming stock price swings.

- Realistically, the price-to-book value would also fall, causing even bigger price drops. (Truist's price-to-book value has fallen from 1.03 to 0.67 since March 9.)

- The most important asset at any bank is the trust of its customers. When those customers see their bank's share price spiraling downward, and also see headlines of other banks failing, they lose that trust and pull their money out, further endangering the bank.

The bottom line: Right now, millions of Americans really care about the price of bank stocks, and are treating share prices as an indicator of healthiness.

- If investors sell bank shares on worries they might go to zero, those concerns can become self-fulfilling prophecies.