Scientists coax cells to mimic earliest human embryo stage

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

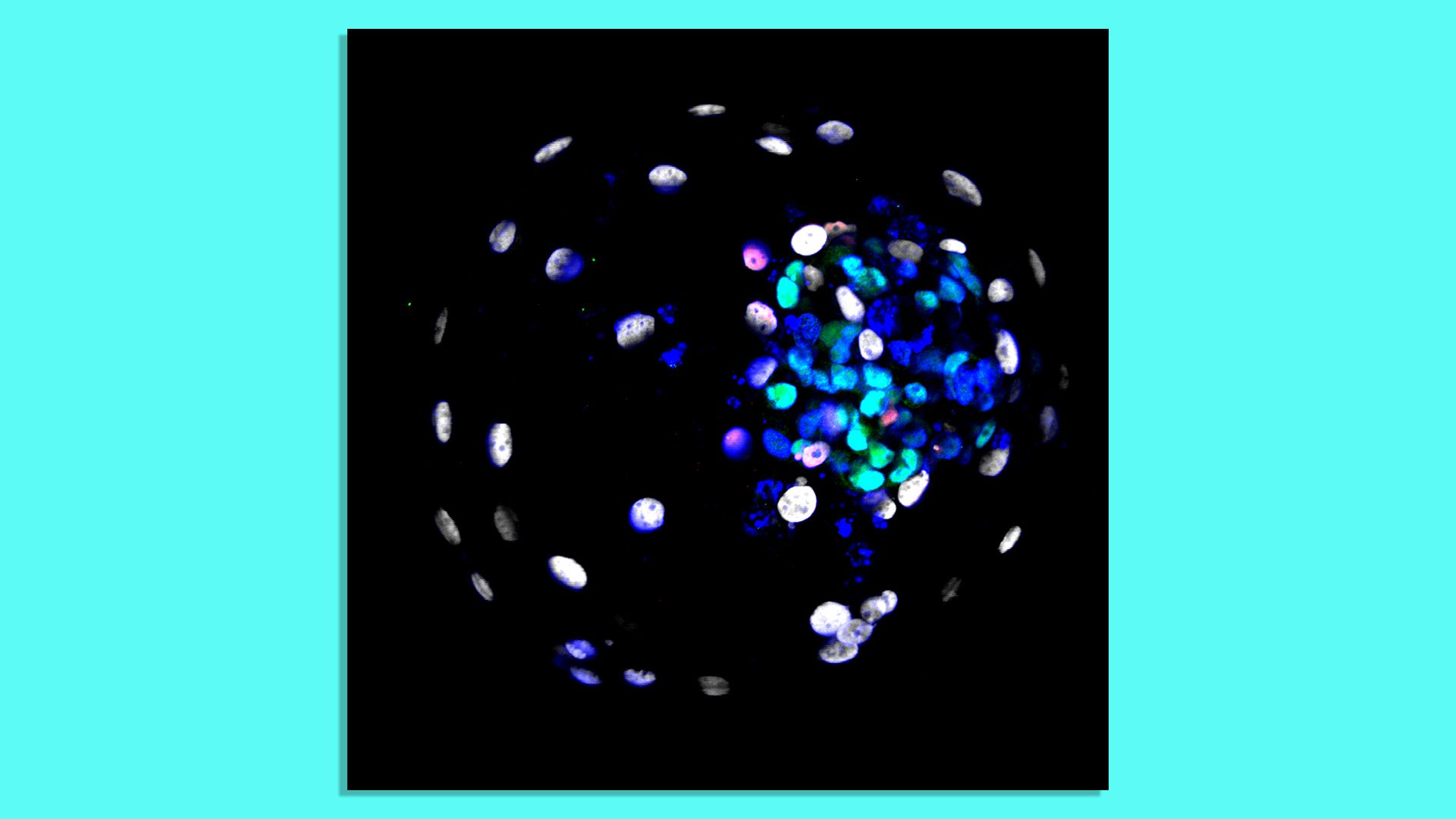

A human blastoid with all three cell types typically found in a human blastocyst: trophoblast (white), epiblast (green) and hypoblast (red). Blue indicates the nucleus from all cells. Image: Leqian Yu and Jun Wu/University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

Human stem cells can be grown in the lab into balls of cells that resemble embryos in the earliest stages, researchers report today.

Why it matters: The models of the earliest days of human development could help to determine how pregnancies are lost and which genetic mutations can lead to birth defects. They could also be used to screen the effect of drugs on human development and improve IVF therapy success rate.

“Studying human development is really difficult, especially at this stage of development. It’s essentially a black box," Jun Wu, a developmental biologist at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and an author of one of the studies, said in a press briefing.

How it works: A key step in human development occurs about five days after an egg is fertilized by sperm, when the egg divides and forms a structure called a blastocyst with cells inside that become an embryo.

What's new: In two separate papers published today in Nature, researchers used human embryonic stem cells and skin cells from adults that were reprogrammed to act as stem cells to create structures called "blastoids" that are similar to blastocysts. Two other recent studies, yet to be peer-reviewed, also mimicked early developmental events.

- Growing the cells for six to eight days in culture medium with different chemicals nudged them into forming tiny blastoids.

- The morphology, size, and number and types of cells in the blastoids were similar to those in human blastocysts, the researchers report, as were the expressions of genes.

- And they found some of the blastoids attached to the culture dish after four to five days — mimicking the process of blastocysts attaching to the uterus.

Yes, but: There are molecular differences between blastoids and blastocysts, and the models generated cell types not found in natural blastocysts, suggesting the blastoids wouldn't develop into viable embryos, the researchers said.

- Amander Clark, who studies stem cell biology at the University of California Los Angeles and is an author on one of the papers, said the protocols used by the research groups wouldn't be used to make embryos for IVF.

- The approach could instead be used to generate hundreds of identical blastoids that scientists could employ to test the effects of drugs, viruses and other toxins on these early stages, Monash University stem cell researcher Jose Polo, who collaborated with Clark, said in the briefing.

The big picture: Researchers are rapidly developing models of human development and of the brain — events and regions that are not easily accessible.

- Studies of early human development are currently limited by the number of blastocysts, which are typically donated by couples after IVF, available for research — and the ethical concerns the work raises. In many countries, there's a 14-day rule — and in some places it is law — that scientists aren't permitted to allow human embryos to develop more than two weeks. (There are now calls to ease that limit.)

- The researchers said blastoids would allow labs to test hypotheses about human development without using human embryos and stressed that the new models are good enough to answer a host of open questions.

But, if these models become more sophisticated, they could raise ethical issues of their own. If they are equivalent to natural embryos, the 14-day rule should apply, says Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University and Harvard Medical School who argues for extending the time limit.

- "It should be defined by what it can do, not how you made it."