Here's what the U.S. antitrust case charges Google with

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

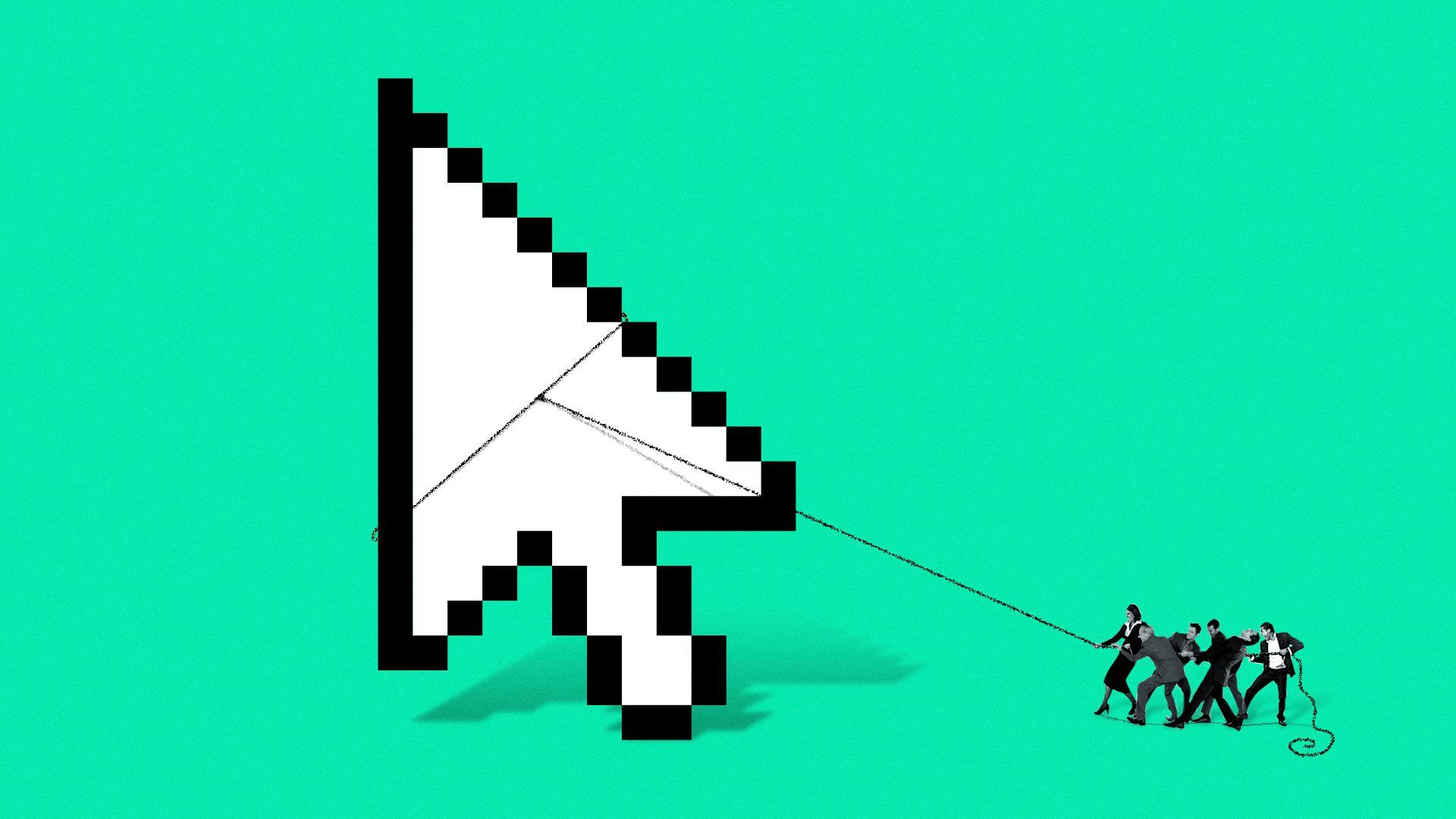

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

The Justice Department's new antitrust lawsuit against Google centers on the charge that Google has built a self-reinforcing machine to illegally insulate it from any serious competition in search.

Why it matters: DOJ spent more than a year investigating Google to assemble what prosecutors believe is the cleanest case for convincing a court that the company is deliberately hamstringing would-be competition. Both sides now face the likelihood of a bruising, years-long battle that could expand to touch on other aspects of Google's business.

The big picture: Others have raised antitrust concerns around Google's other lines of business, such as the video ads attached to YouTube clips and the technology that powers its ad platforms.

- DOJ avoided getting drawn into philosophical and practical debates around defining such markets by zeroing in on the one that Google unambiguously dominates: searching for general information on the internet.

Of note: Prosecutors have to prove that Google holds not just a monopoly, but a harmful monopoly in a clearly defined market.

- Google's services are mostly free to consumers, which makes it tough to demonstrate how its market dominance harms them.

- In its suit, the DOJ argues consumers are harmed because Google's anti-competitive behavior ends up "reducing the quality of general search services (including dimensions such as privacy, data protection, and use of consumer data), lessening choice in general search services, and impeding innovation."

The suit focuses on arrangements Google has made to share ad revenue with wireless carriers, device makers and web browser developers in exchange for locking in its search engine as the default. The deals artificially constrain competition for two reasons, the DOJ suggests throughout its suit:

1. Opting out of these arrangements is bad for business. The code powering Google's Android operating system is open source, meaning any device maker can use it as the basis for their own mobile OS.

- But for third parties putting Android on their devices, inking a revenue-sharing agreement with Google is the only way to get full functionality out of the operating system.

- Apps running on alternative versions of Android, like Amazon's Fire tablets, can't do things like pull in data from Google Maps or offer in-app purchases via the Google Play store.

2. Inertia keeps people from changing their search engine default. That in turn makes it unattractive for Google partners to switch to an alternative deal with a competing search provider.

- They'd have to not only make the other provider the default for new users but count on all existing users to switch over in order to match the revenue from their Google arrangements.

- "[B]eing preset as the default is the most effective way for general search engines to reach users, develop scale, and become or remain competitive," the lawsuit contends.

The upshot: Companies that might otherwise challenge Google in search, DOJ maintains, are put at a serious competitive disadvantage in getting people to even try out their products.

Google's structural advantages are self-reinforcing, DOJ says.

- More usage yields more data on what users find and click through as they search. More data yields a better product. A better product yields more usage.

- To Google, this represents a virtuous spiral of innovation and refinement. To DOJ's antitrust enforcers, it's a vicious circle that's helped Google break away from would-be competitors.

By the numbers: That includes even companies like Microsoft. It's one of the few firms with enough money and technical expertise to stand up a search challenger — but its Bing search engine has proven unable to make more than a dent in Google's dominance.

- In the suit, DOJ says Google controls 88% of the general online search market, to Bing's 7%. Yahoo, which simply repackages Bing results under a deal with Microsoft, has less than 4%, while privacy-centric alternative engine DuckDuckGo has less than 2%, DOJ says.

Yes, but: Google has one big rejoinder to all these claims:

- "[P]eople don’t use Google because they have to, they use it because they choose to," global legal chief Kent Walker wrote in a Tuesday blog post.

- "This isn’t the dial-up 1990s, when changing services was slow and difficult, and often required you to buy and install software with a CD-ROM," he continued. "Today, you can easily download your choice of apps or change your default settings in a matter of seconds."

What's next: The suit warns that unless the government reins Google in, it will take the unfair advantages it has accumulated in the mobile era and port them to the next generation of connected devices.

Go deeper: