Trying to prevent cancer cells from metastasizing

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

A signal between breast cancer cells could be a target for new drugs to block the cells from clustering, migrating and metastasizing, researchers said in early findings published in Cell last week.

Why it matters: Metastatic tumors kill nearly 43,000 people from breast cancer, 33,000 from prostate cancer and 135,720 from lung cancer in the U.S. every year. Scientists are seeking ways to prevent a person's cancer from spreading to other organs and becoming more deadly.

Background: Metastatic cancer was thought to mainly originate from single cancer cells traveling to other parts of the body. But there's growing evidence that, at least in some cancers, tumors are more likely to spread throughout the body if they cluster together before traveling through a process called collective cell migration, or collective metastasis.

- "In this particular study, we show there's a 500-fold increase in metastasis formation for cluster tumor cells [CTCs] compared with the equivalent number of individual tumor cells," study co-author and medical oncologist Kevin Cheung tells Axios.

- Patients with CTCs tend to have "markedly worse clinical outcomes," says Cheung, assistant professor of the public health sciences division at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

- CTCs can range from three to dozens of cells that separate from the primary tumor and travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system.

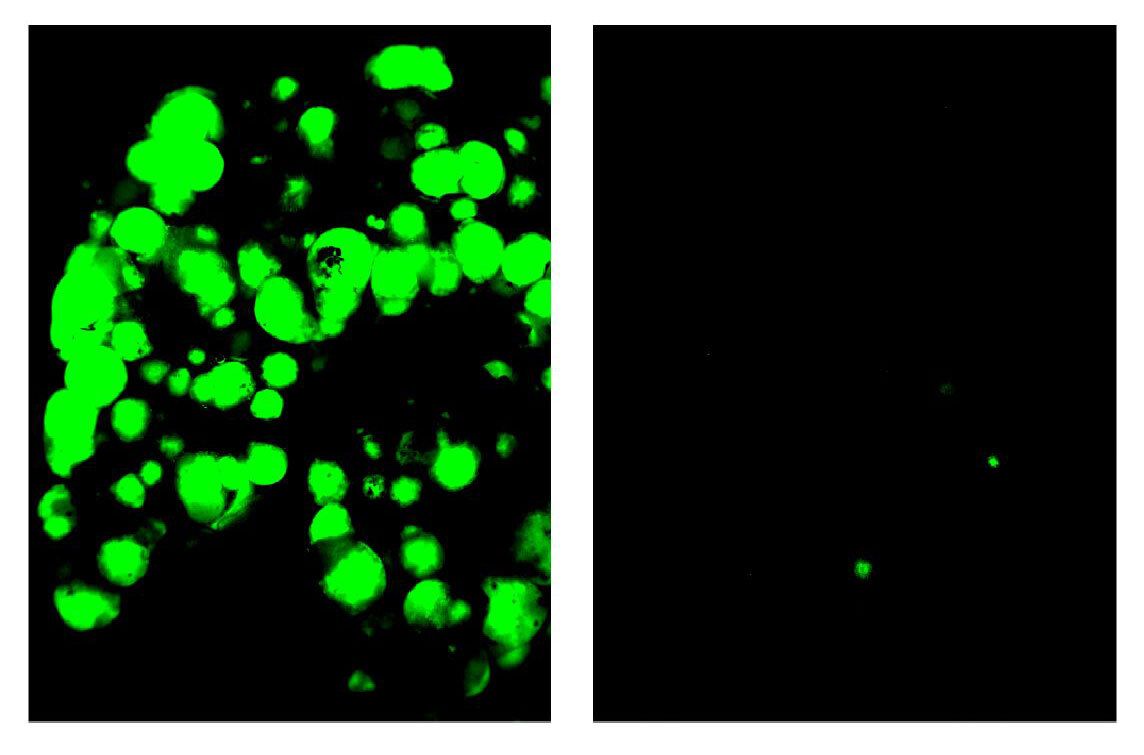

What they found: Using high resolution imaging to examine clusters of breast cancer cells in mouse and human models, the team discovered a space called "nanolumina" between the cells of each cancer cluster where the cells co-opt a signaling molecule called epigen to promote the growth of clusters.

- Epigen appears to be accumulating between these nanolumina at about 5,000 times higher concentration than the fluid outside the structure, Cheung says.

- They found when epigen was suppressed within the nanolumina, primary tumor and metastatic outgrowth was greatly reduced.

- "Epigen is like a toggle switch. When epigen is high, cluster tumor cells divide and proliferate. ... If we block the epigen within these [nanolumina] compartments, we block metastasis," Cheung says.

What they're saying: Several scientists, who were not part of this study, said finding the nanolumina and epigen is an important early step in better understanding breast cancer metastasis that might later be found to apply to other cancers, too.

- "These findings are very important and new. Most breast cancer patients are not dying from the primary tumor but from metastasis of their tumors," says Priscilla Hwang, assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Virginia Commonwealth University.

- "While this study focused on breast cancer, this could potentially be a target to look at for many other cancers as well. Obviously that's not been done yet, but the potential is there," says Aleks Skardal, assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Ohio State University.

- "Since a lot of metastatic therapies have been designed based on our understanding of single cell metastasis, this may be part of the reason why many therapies have not been effective for treating metastasis," Hwang says.

What they don't know: This may be a general approach for metastasis for different tumor types, but they don't yet know how many tumor types have nanolumina, Cheung says.

- And any drug therapy targeting epigen would need to be a "balancing act," Skardal points out, as the molecule also plays an important role in normal cell growth.

What's next: After further research, "the next steps are figuring out how to weaponize this against cancer," Skardal says.