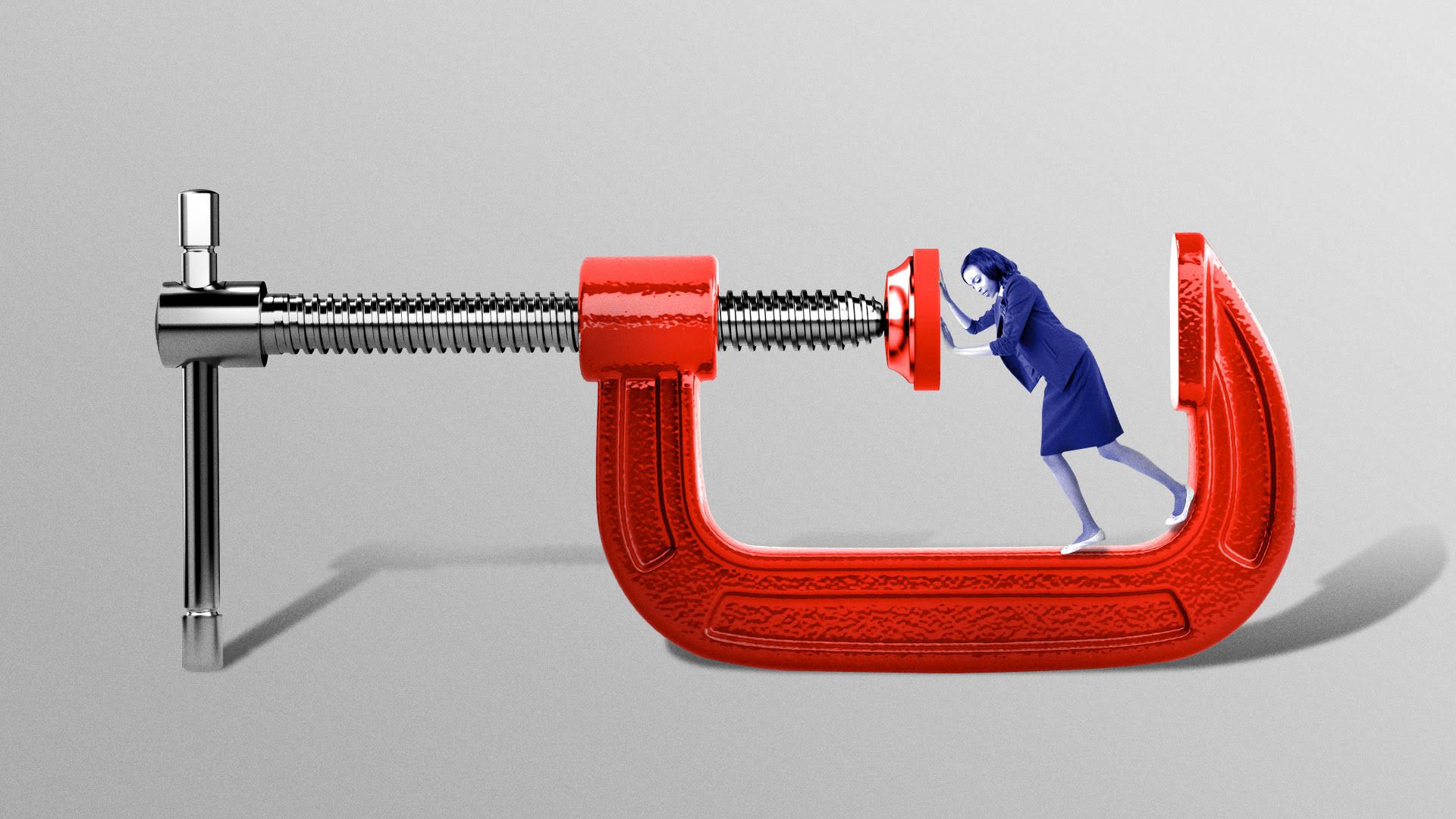

Coronavirus squeezes the "sandwich generation"

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

As the coronavirus poses risks and concerns for the youngest and oldest Americans, the generations in the middle are buckling under the increasing strain of having to take care of both.

Why it matters: People that make up the so-called sandwich generations are typically in their 30s, 40s and 50s, and in their prime working years. The increasing family and financial pressures on these workers means complications for employers, too.

The big picture: The pandemic has forced members of the sandwich generation to make near-constant, stressful decisions about how to safely care for their own young children with schools and day care facilities closed, while also trying to reduce health risks for elderly parents and grandparents.

- The elderly parents present a special challenge if they need extra help at home or live in residential facilities with disproportionately high COVID-19 infection rates.

- And grandparents are often back-up child care. But many parents are wary of asking grandparents to watch children and possibly expose them to dangerous germs in the process, thus putting more pressure on parents to find alternatives.

- "There's a lot more stress and decision-making involved than there is for other generations that don't have that challenge," said Melissa Whitson, associate professor of psychology at the University of New Haven.

By the numbers: According to the Pew Research Center, 47% of adults in their 40s and 50s have a parent 65 or older and are also either raising young children or financially supporting a child 18 or older.

- 15% are providing financial support to both an aging parent and a child, per Pew.

- 38% say both grown children and parents rely on them for emotional support.

What it means for employers: Before the pandemic, two out of five employees felt that their futures could have been negatively impacted if they took advantage of flexibility options to manage their personal lives, according to a Society for Human Resource Management survey.

- "Providing access to flexibility—which many employees now have during the pandemic—is a floor; it is necessary but not sufficient," the Family and Work Institute stated in an April report. Most important is ensuring employees feel supported by supervisors and co-workers to take advantage of flexible work policies.

The big question: How flexible employers are willing or able to be for workers who are not only worried about their own health during the pandemic, but also the health of the generations they support, said Francine Blau, Cornell University professor of economics and industrial and labor relations.

- In some cases, she said, workers may just have to quit their jobs or look for another job that has more flexibility to work from home or during off-hours. But that's a precarious position to be in during a recession.

What to watch: "Just like child care, women do a disproportionate amount of parent care of older family members," Blau said. "This puts more stress on women...I am concerned some will fall out of the labor force."