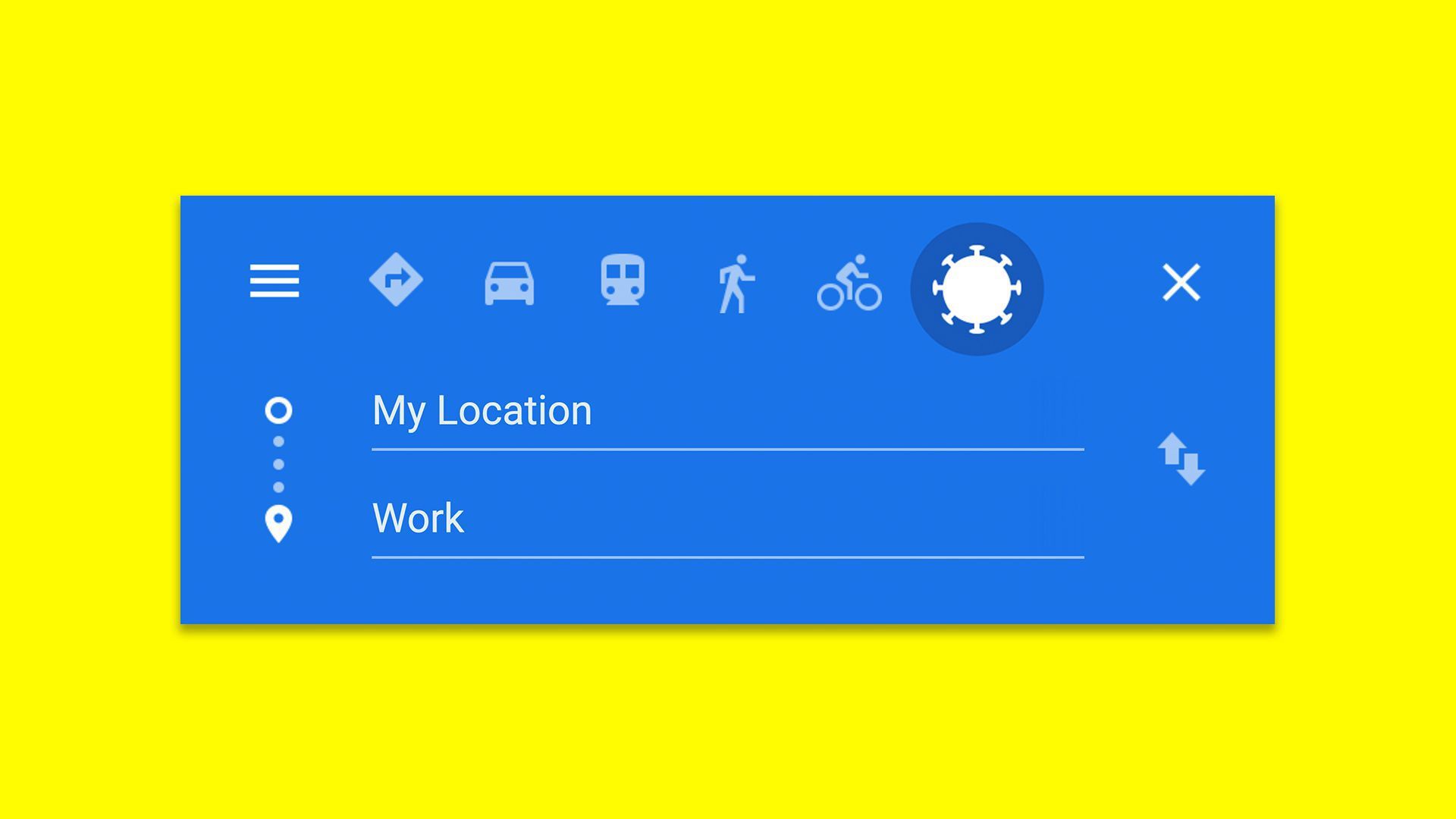

Coronavirus is reshaping urban mobility

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

The coronavirus pandemic is remaking city landscapes worldwide, and the ultimate scope and duration of the changes will influence the future of urban mobility, pollution and even global oil demand.

Driving the news: Many cities are changing street uses and restricting cars (to varying degrees) to create new and socially distant opportunities for pedestrians, cyclists and diners.

- New York City has begun opening up to 100 miles of streets, while Oakland is altering the use of 74 miles and Seattle is permanently restricting 20 miles of streets.

- London's mayor this month announced plans to "rapidly transform" city streets to handle more walkers and bikers, while major changes are underway in Paris too, where officials are planning hundreds of miles of new bike lanes.

What we're watching: There could be colliding interests as commuting begins to revive while open space and environmental advocates fight to preserve and expand the newly airy spaces.

By the numbers: There's no precise tally of the breadth of the global changes, and policies around wider sidewalks, vehicle access and speed limits, bike paths and more vary in stringency and specifics.But Mike Lydon of the urban planning firm Street Plans created a continuously updated public database that shows nearly 1,700 miles worth of streets affected by announced or implemented changes.

Why it matters: Cities face a new reality of uncertain duration even as restrictions are eased. Public transit systems must run at greatly reduced capacity thanks to social distancing and budget woes, and passengers may stay away to avoid exposure.London, in announcing its plan, warned that a mass exodus to private cars would worsen congestion and air quality.

The intrigue: Changes unfolding because of the health emergency are reinforcing a pre-pandemic movement to end cars' dominance over urban landscapes.

- The amount of vehicle traffic affects air pollution, CO2 emissions. And the post-pandemic future of commuting is even one of the many forces that will affect the level of post-crisis oil consumption.

- It's also all occurring as cities adjust to wider use of micro-mobility options like scooters and bike-shares.

The big question: How many of these changes will be made permanent even once people are largely able to return, in theory, to pre-crisis norms?

- Officials in Paris and London, for instance, have signaled that the changes could last, and Lydon tells me that European city officials are keen to improve air quality and address climate.

But, but, but: Cities could face pressure in the other direction. There's already evidence that driving levels are bouncing back from April's troughs in a big way.

- "Many transportation planners are concerned that the combination of reduced capacity, as well as fears of using transit in a pandemic world, will result in a shift towards personal vehicles," said Regina Clewlow, CEO of Populus, which provides transportation data analytics to local governments.

- However, it's unclear how much the increased driving that stems from mass transit's new problems will be offset by people working from home for a long time and even permanently.

It's hard to say at this point how much of the changes to U.S. streetscapes will stick around long after the pandemic, but some experts expect lasting changes.

What they're saying: Urban transportation expert Yonah Freemark points out that in the 2000s, New York City's then-transportation chief Janette Sadik-Khan experimented with pro-pedestrian and cycling changes. Many became permanent.

- "I expect we will see similar results in many of the places where cities are implementing slow streets, expanding cycling infrastructure, and widened sidewalks," said Freemark, who authors The Transport Politic website.

- "The clear benefits these improvements provide to neighbors, as well as their limited negative impacts on traffic, will likely build support for them, and make it difficult for political officials to walk back on these policies," he tells Axios.

The bottom line: "A moment like this — when millions of urban trips are temporarily up for grabs across transportation modes — is exceedingly rare. The stakes for cities could scarcely be higher," said Harvard Kennedy School urban expert David Zipper, writing in Slate.

Go deeper: Coronavirus may prompt migration out of American cities