How art can help us understand AI

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

Photo: Ina Fried/Axios

Activists and journalists have been telling us for years that we are handing too much of our human autonomy over to machines and algorithms. Now artists have a showcase in the heart of Silicon Valley to highlight concerns around facial recognition, algorithmic bias and automation.

Why it matters: Art and technology have been partners for millennia, as Steve Jobs liked to remind us. But the opening of "Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI" tomorrow at the de Young Museum in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park puts art in the role of technology's questioner, challenger — and sometimes prosecutor.

The big picture: "Uncanny Valley" confronts exhibition goers with powerful images of data monetization, algorithmic bias and the loss of humanity.

For one of several pieces in the exhibit, Agnieszka Kurant relied on millions of collaborators.

- Titled "AAI" (short for "artificial artificial intelligence," a Jeff Bezos coinage referring to human-powered pseudo-AI), the piece consists of several colorful mounds that were constructed over several months by different colonies of termites out of a range of materials including sand, gold particles and broken crystals.

- Kurant said the piece is inspired by the exploitation of labor in late capitalism, as well as the mining of rare materials.

- "Essentially these sculptures are models for this hidden exploitation and the entire society becoming one gigantic factory," Kurant said.

Another piece by Kurant, "Conversions #1," uses sentiments from tweets from activists around the world to manipulate liquid crystal paint on an interactive canvas.

- "Even our protests against the status quo are becoming a source of extraction of information about us and are becoming monetized," Kurant said.

Other pieces of note:

- Simon Denny built a version of an Amazon patent — specifically a 2016 design for a cage to allow a human worker to navigate through an automated warehouse. Viewed through a phone app or an iPad supplied by the museum, the cage reveals a trapped King Island brown thornbill — an Australian endangered bird.

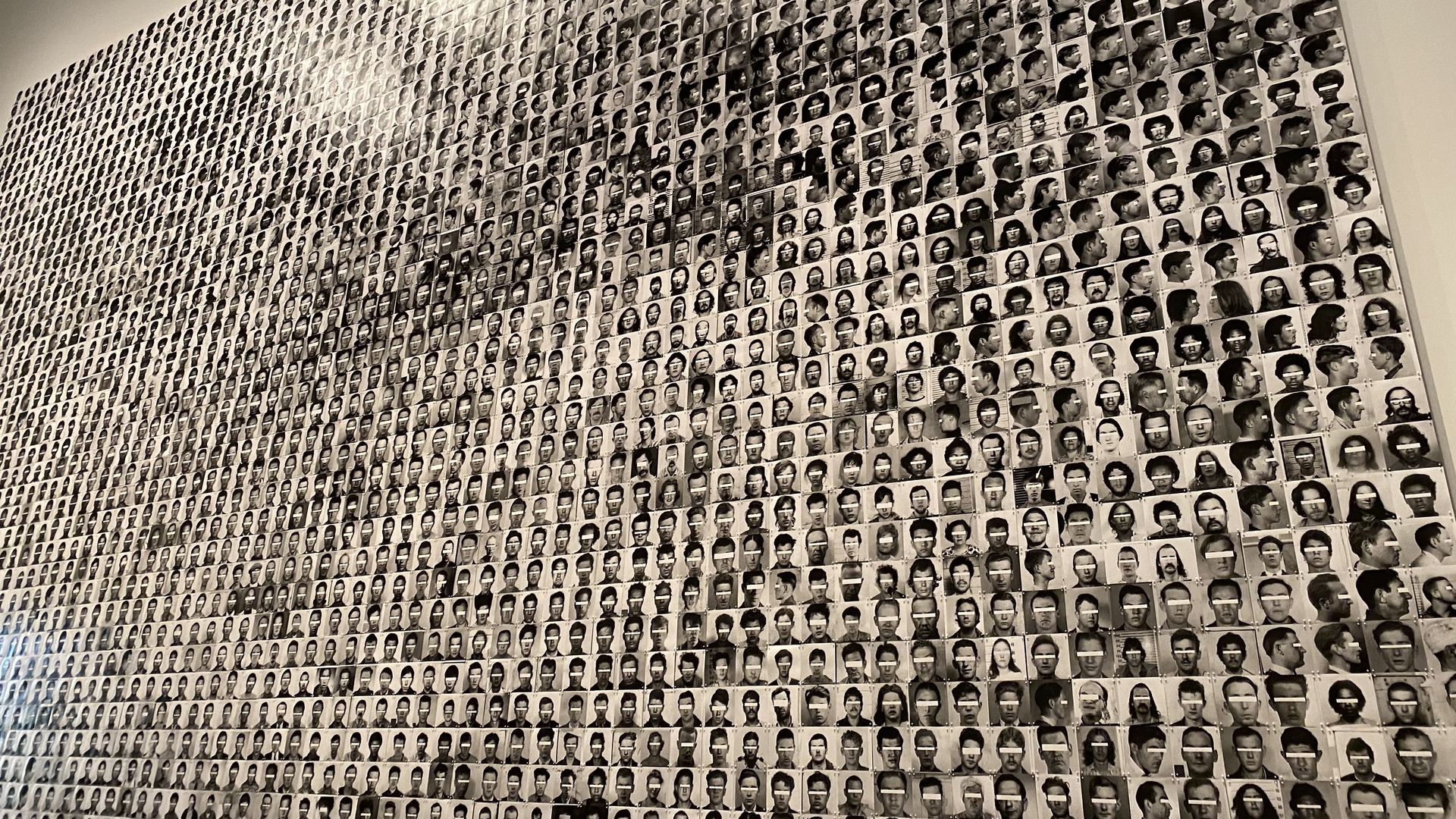

- Trevor Paglen's "They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead" consists of hundreds of faces used to train an artificial intelligence engine, all without any of the subjects' consent. "What we are looking at here is dirty data," curator Claudia Schmuckli said.

- Ian Cheng's "BOB (Bag of Beliefs)" presents an on-screen "virtual serpent" —inspired by the designs of animator Hayao Miyazaki — that viewers can interact with via a mobile app. Given enough attention and care, the critter will leave the exhibit's monitors and crawl onto spectators' own devices. The piece aims "to remind viewers that an AI entity like BOB should not be treated as omniscient or static. Rather, it should be approached like a child or an animal."

- Lynn Hershman Leeson's piece "Shadow Stalker" illustrates the volume of personal information on the web. Enter your email and the exhibit starts showing a list of places you've been, people you know and your phone numbers (albeit with some parts redacted). Another piece from Leeson, a video, highlights the dangers of predictive policing.

"Tech is never neutral," said Schmuckli. "That is a myth."

My thought bubble: This exhibition has a way of cutting to the heart of the issues in ways that all of the legislative proposals and interest group statements don't, even as they raise similar concerns.

Details: The exhibit runs through Oct. 25. If you are going to be in the Bay Area between now and then, it's definitely worth checking out.

Go deeper: A tug-of-war over biased AI