Jan 2, 2019 - Science

The most distant space object ever visited looks like a red "snowman"

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

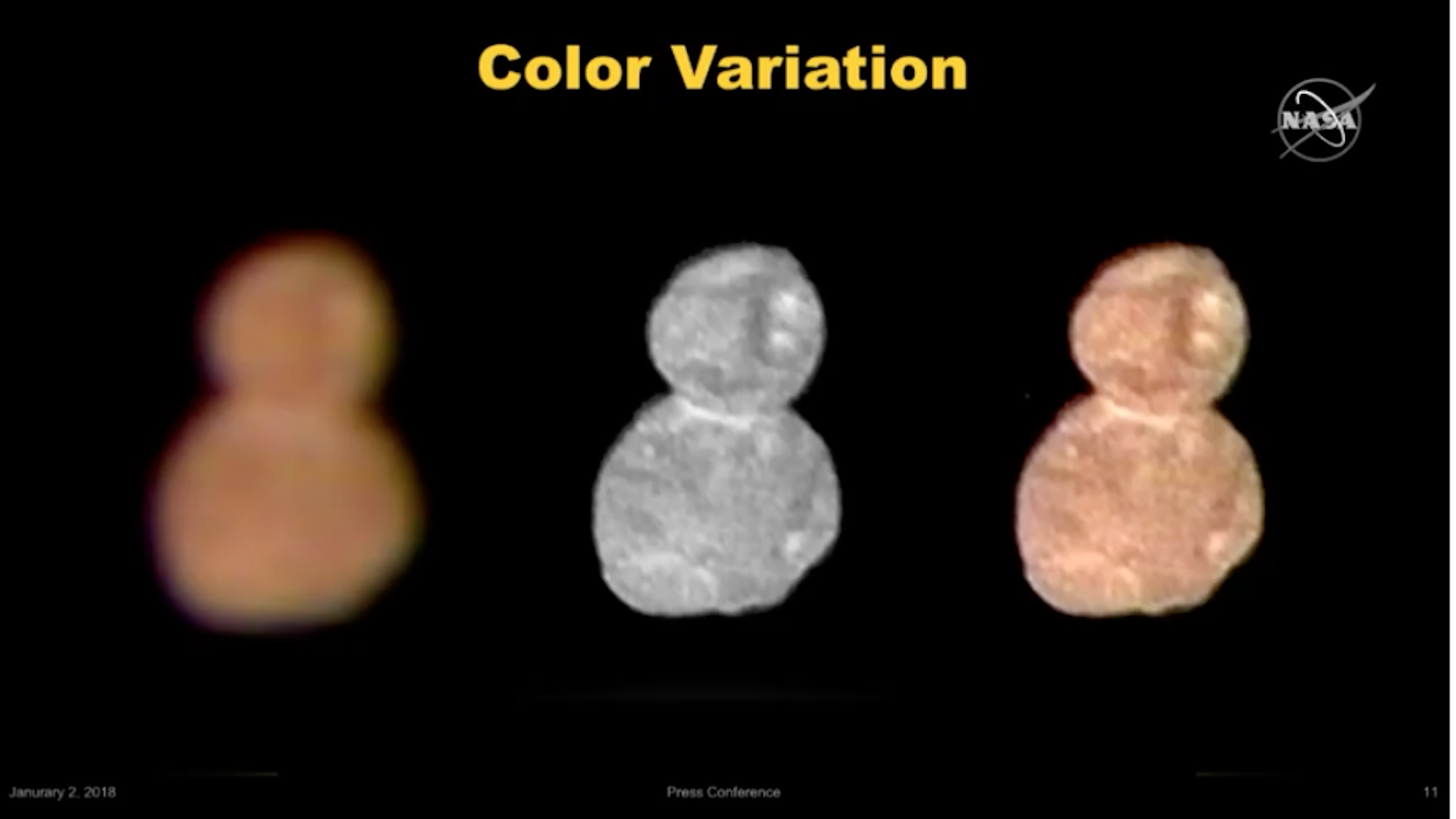

The first color image of Ultima Thule, taken at a distance of 85,000 miles on Jan. 1, 2019. Left and right-most images use near infrared, red and blue channels. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.