Updated Mar 14, 2018 - Technology

Robots are shifting income from workers to owners

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

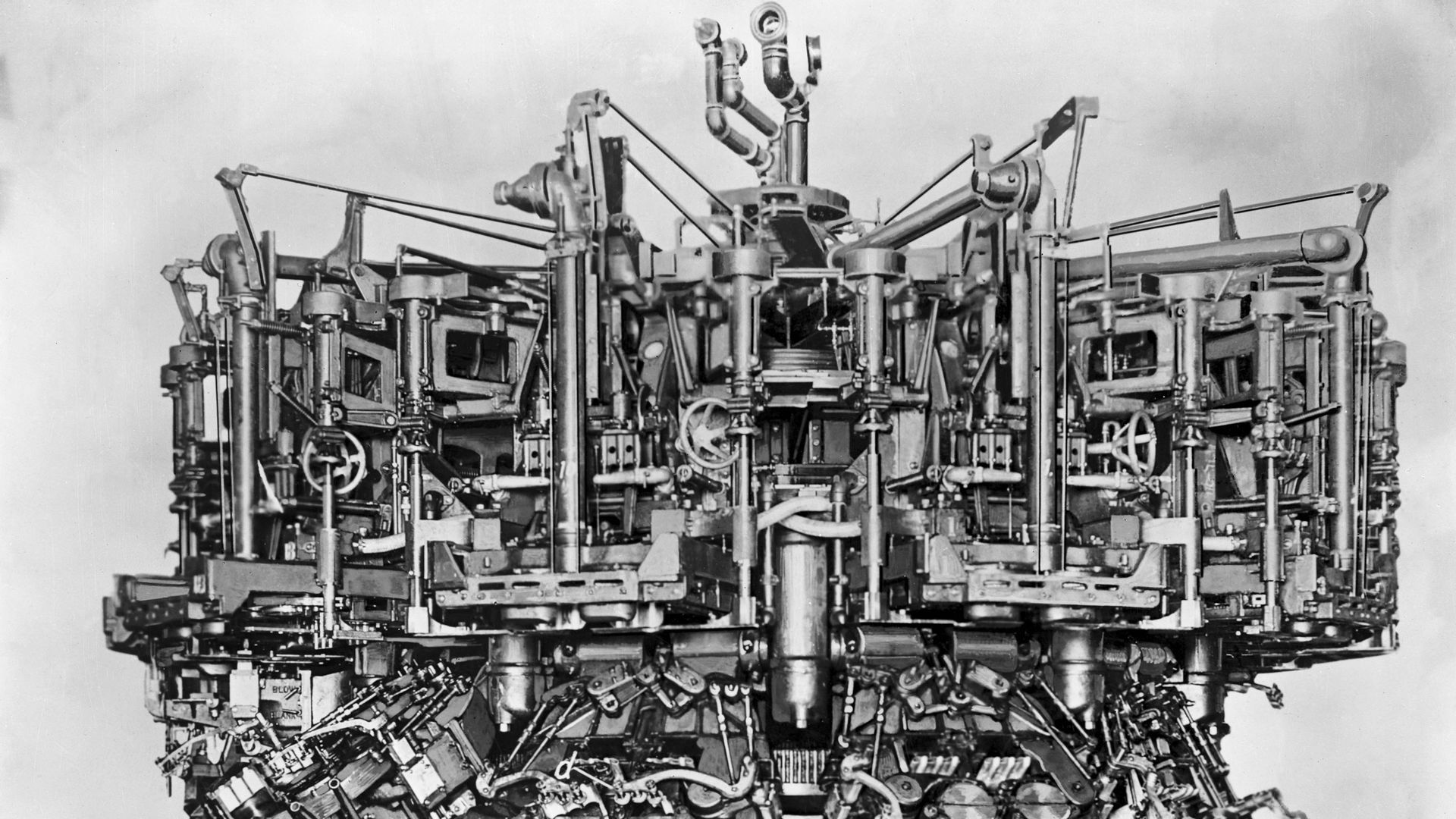

Michael Owens' breakthrough bottle-making machine, 1907. The machine displaced glass-blowers. Photo: Science & Society Picture Library / Getty.