Axios Vitals

October 30, 2019

Good morning. Today's word count is 910, or ~3 minutes.

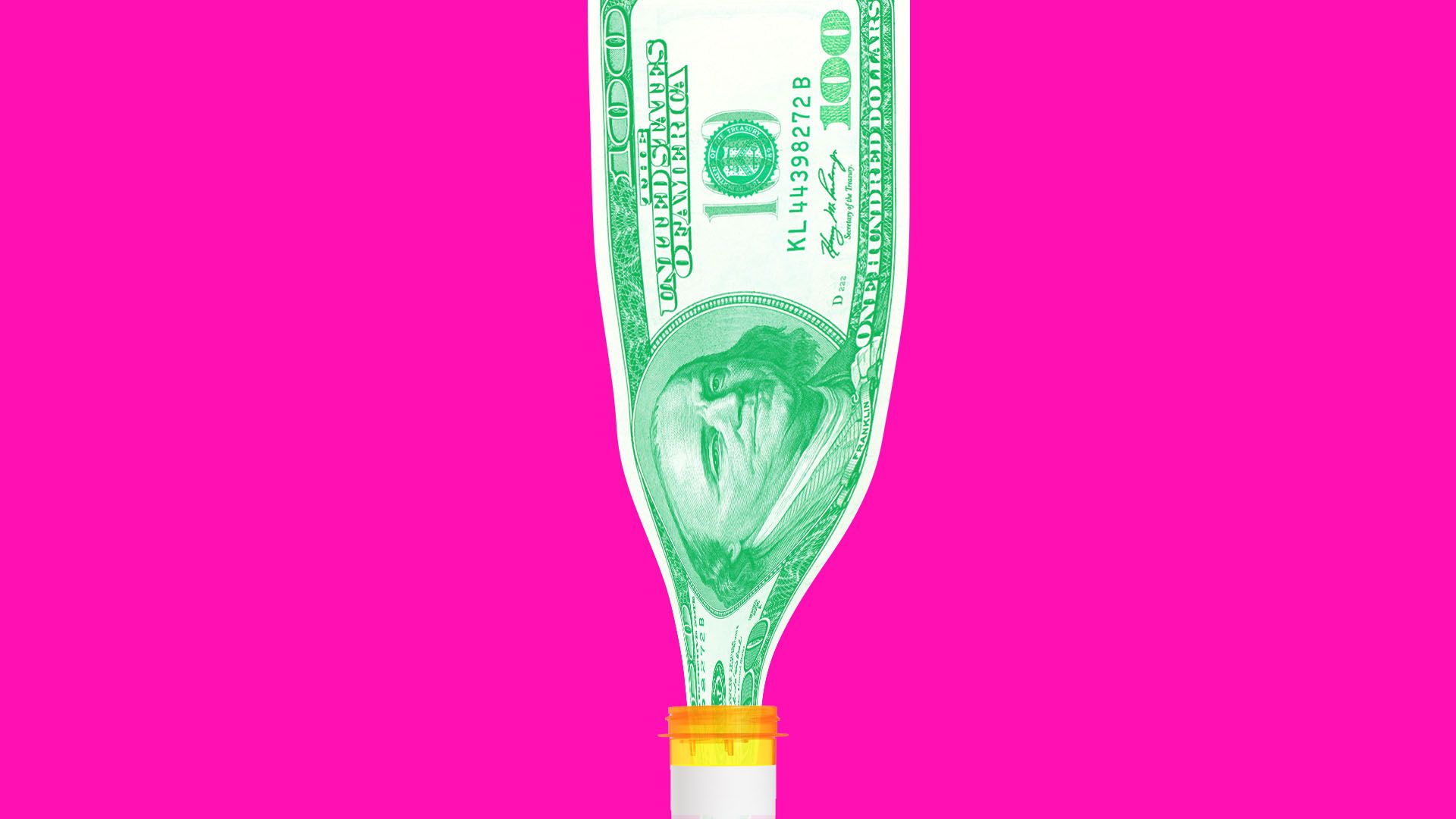

1 big thing: Lipitor is still churning out billions of dollars

Lipitor, the cholesterol-lowering medication that has become the gold standard of statins, continues to generate roughly $2 billion per year in sales for Pfizer, even though its patent expired eight years ago.

The big picture: Almost all of Pfizer's Lipitor sales now come from China and other emerging markets, Axios' Bob Herman reports.

- But Lipitor's ability to remain a blockbuster drug, even with so many generic competitors that cost pennies per pill, shows how distorted the global pharmaceutical system can be.

By the numbers: Worldwide Lipitor sales peaked in 2006, at almost $13 billion, with more than 60% coming from the U.S.

- After Lipitor's patent lapsed in late 2011, sales started declining precipitously in the U.S. as numerous generic atorvastatin pills hit the market.

- But since 2014, annual sales have hovered around $2 billion thanks to the gigantic Chinese market.

- Pfizer has frequently won bids to sell Lipitor in Chinese hospitals, "as they could more easily offer quality assurances for their higher-cost medicines," Bloomberg reported earlier this year.

- But after losing a large hospital bid last year, Pfizer lowered Lipitor's price in China by 30% "in the hope patients would buy it privately," the Financial Times reported.

Between the lines: Lipitor is mostly bought overseas but holds a small pulse domestically. Pfizer is on pace to sell roughly $100 million of the statin in the U.S. this year.

- That isn't a lot of money broadly speaking. But it still means patients, health insurance programs and taxpayers are paying upwards of $14 per Lipitor pill when generic equivalents cost less than a dime per pill.

- Pfizer didn't immediately respond to questions.

The bottom line: Lipitor remains a global money-maker for Pfizer despite generic competition.

Go deeper: Generic drugs aren't always favored

2. The risks of private equity in health care

Private investment into the health care sector may bring innovation, but it's also led to revenue-seeking behaviors at the expense of patients, three employees of The Commonwealth Fund argue in Harvard Business Review.

By the numbers: There were nearly 800 private equity health care deals in 2018, with a total value of more than $100 billion.

Surprise medical bills have recently put private equity in the spotlight.

- Many of these bills are generated by specialties commonly backed by private equity, like emergency room care, anesthesiology and radiology.

- One of the biggest political forces lobbying against Congress' effort to stop surprise medical bills is a group called Doctor Patient Unity, which has spent more than $28 million on ads and is primarily funded by private-equity-backed companies.

The big picture: Physician practices are a common target for private equity firms.

- These investments may give small practices an alternative to being bought by hospitals, "but, at least in some cases, the investors' strategy appears to be to increase revenues by price-gouging patients when they are most vulnerable," the authors write.

- Freestanding emerging rooms are also commonly owned by private equity. These have come under fire for their high prices, which can be 22 times higher than what a physician's office charges for the same care.

The bottom line: Price-gauging patients may backfire. "Consumer outrage leads quickly to government intervention," the authors conclude.

3. Employers rely less on high-deductible plans

Illustration: Rebecca Zisser/Axios

Some employers are returning to offering traditional health insurance plans again, as opposed to relying solely on those with high deductibles, Kaiser Health News reports with NPR.

Driving the news: The percentage of companies offering high-deductible plans as the only coverage option is declining for the third year in a row in 2020, per a survey of large employers by the National Business Group on Health.

- Only 25% of firms will offer them as the only option next year, which is 14 percentage points less than two years ago.

Employers say that offering plans with no or lower deductibles can be a recruitment tool, and some employees would rather have higher premiums in exchange for more predictable health care costs.

Yes, but: High deductible plans are still popular; 58% of employees with health coverage worked at a company that offered at least one high-deductible plan in 2019, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Our thought bubble: The push of health care costs onto employees via their out-of-pocket costs has been unpopular and untenable, and employers are responding.

- Also untenable: The rising overall cost of employer health care.

Go deeper:

4. America's health in 5 stats

New data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics show a gloomy state of the nation's health, particularly in terms of fertility rates and life expectancy at birth, Axios' Marisa Fernandez writes.

- Fertility rates: The number of live births per 1,000 females ages 15–44 has fallen 10 out of the last 11 years.

- Drug overdoses: The death rate increased 82%, from 11.9 to 21.7 deaths per 100,000 people between 2007 and 2017.

- Health care spending: Expenditures added up to nearly $3 trillion in 2017, almost a 4-point increase from 2016.

- Prescription drugs: 11% of Americans said they took five or more prescriptions within 30 days in 2016.

- Vaping: 1.5% of students in grades 9–12 used e-cigarettes in 2011. In 2018, it was 20.8%.

Yes, but: The teen birth rate dropped more than 50% from 2007 to 2017.

5. FDA committee recommends drug withdrawal

An FDA advisory committee yesterday voted to recommend that Makena, a treatment to prevent women from having a pre-term birth, be withdrawn from the market after a study found that it's ineffective, the Wall Street Journal reports.

Backdrop: The FDA approved the drug in 2011, but required a follow-up study. That study came out last week and found that the drug — which has become the standard treatment — doesn't decrease recurrent preterm births.

What they're saying: "At the end of the day we want to be giving pregnant women medications that work and help them and their babies," Adam Urato, chief of maternal-fetal medicine at MetroWest Medical Center in Framingham, Mass., told the Journal. "This drug doesn't work."

Go deeper: When an expensive drug turns out to be a dud

Sign up for Axios Vitals

Healthcare policy and business analysis from Tina Reed, Maya Goldman, and Caitlin Owens.