Axios Future

July 30, 2019

Have your neighbors signed up?

Today's Smart Brevity count: 1,094 words, a 4-minute read.

What else should we write about this summer? Hit reply to this email or message me at [email protected], Kaveh Waddell at [email protected] and Erica Pandey at [email protected].

Okay, let's start with ...

1 big thing: Counter-drone defenses

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

The wildly unpredictable potential actions of drones are driving a new industry that promises to detect, jam, take over, or just plain shoot them out of the sky, Kaveh writes.

- More than 150 companies have already set up shop in a business said to be worth $2.3 billion in 5 years, even though few customers can legally use most of their products.

- But the cowboy quality of some countermeasures creates an impossible choice between an errant drone and its antidote.

Big picture: In recent years, drones have become cheaper and easier to fly, crowding Christmas trees and birthday wishlists to the point that there are now well over a million of them in the U.S.

- In response, government agencies, airports, sports leagues and prisons are scrambling to defend against the dangers posed by a wayward drone.

- They're animated by a drip-drip of stories about drone-related airport shutdowns and prison breaks, and an alarming potential for deadly drone attacks.

But, but, but: As of now, anti-drone technology is still hugely limited, experts say. None of the hundreds of devices on the market will work against every drone, and many don't work at all. "A lot of this is snake oil," says Francis Brown, CTO of Bishop Fox, a security firm.

- Net guns can be defeated with a simple cage built to protect a drone's rotors. Jammers and spoofers — which break a drone's connection to the operator or pretend to be the operator — can't overpower some drones.

- If they do — or if a conventional weapon finds its mark — you've got a new problem: a plunging, spinning, battery-powered drone, perhaps over a parade or stadium.

- Jammers cause another type of collateral damage: they can take down radio, GPS, and wi-fi nearby — which is why the FCC almost never allows them to be used.

What's happening: Police departments are acquiring these devices anyway — even though just 4 federal agencies are currently authorized to bring down drones.

- The L.A. County Sheriff and Oceanside Police, near San Diego, own DroneKillers, a device that overloads airborne drones with a digital signal so that they are forced to land.

- IXI, the California company that makes the DroneKiller, says a third agency in Nevada is about to buy one.

- Andy Morabe, IXI's marketing director, argues that these 3 agencies have been cleared to use counter-drone technology in a signed letter from the FBI director. But both California police departments say they have no such letter.

For now, confusion and legal hurdles are preventing use of the devices.

- The L.A. County Sheriff's Department says neither of their two DroneKillers has ever been fired, and Oceanside's has been shelved for over a year.

- "Any agency that's purchased any counter-drone system, there's no way for them to legally deploy it," says Jason Snead, a policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation.

What's next: Congress has mulled extending the authority to use counter-drone technology to state and local police, but hasn't proposed anything yet. Police departments are clamoring for the permission.

- If that happens, a lack of national standards and rigorous testing — plus a ballooning market — means buyers have to wade through a sea of confounding options to find something that works.

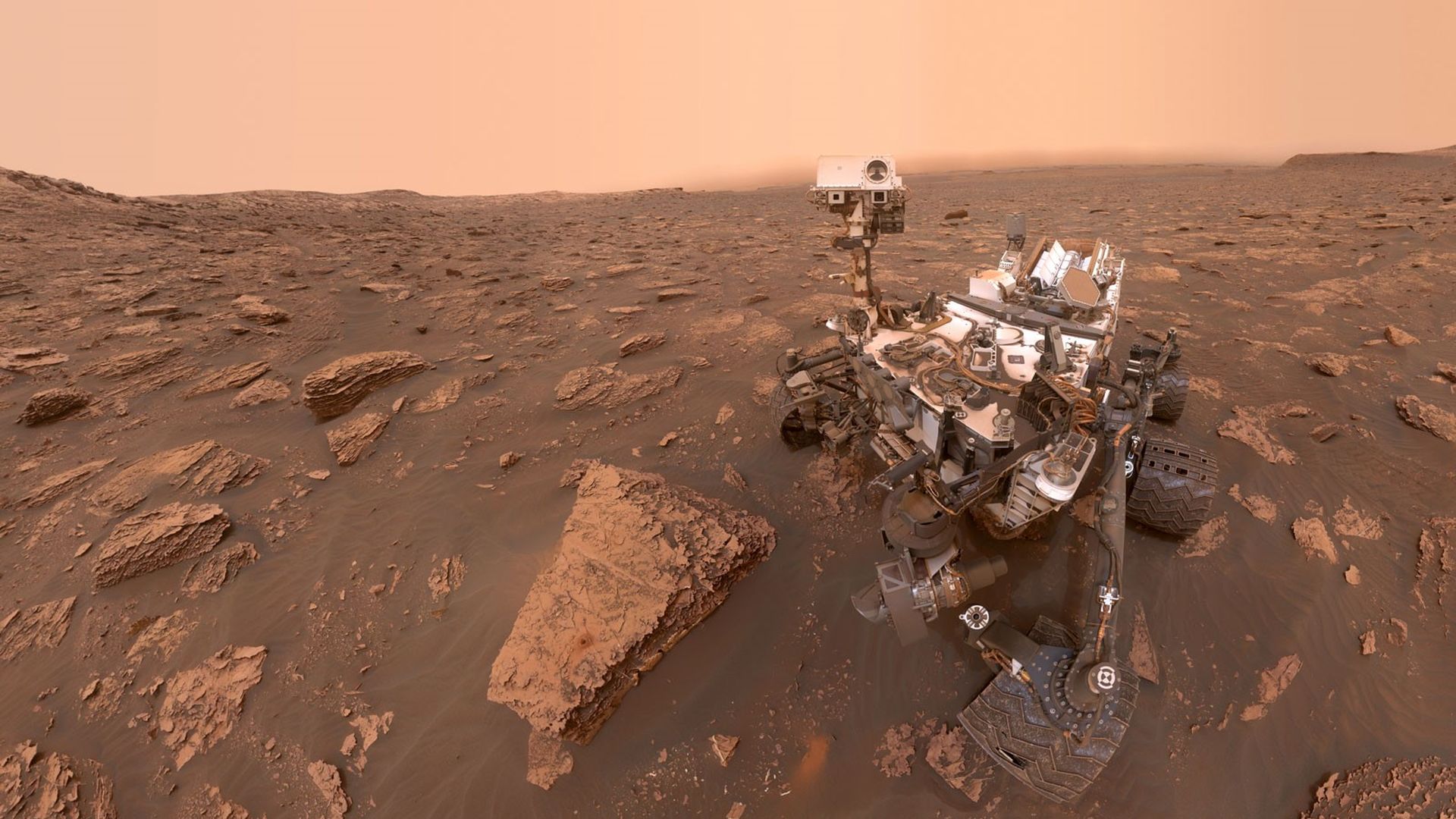

2. Space robots that think for themselves

Curiosity, on Mars. Photo: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/Andalou/Getty

From Earth, you want to pick something up from the surface of the Moon. Using a joystick, you control a grabber — but you keep missing. It's the delay: It takes light nearly 3 seconds to get to the Moon and back, and the control signal even longer, Kaveh writes.

The big picture: This is a fundamental, insurmountable hurdle to moving stuff around in space if you're not there. The farther you are from Earth, the longer the communications delay — nothing, after all, moves faster than light.

- One workaround is to just move really slowly. Fine if you're picking up a rock; not that great if you're trying to build a structure or repair something from afar.

- A more powerful approach is to build as much autonomy as possible into the robot doing the job. That means that instead of telling it to move the grabber forward 2 inches, down 4 inches, and grab, you can just tell it to pick up the rock.

What's happening: Several startups, as well as NASA, are trying to find the right combination of human control and autonomy that would allow robots to do complex tasks in space. Full autonomy isn't an option for now — today's artificial intelligence isn't up to the job.

3. What we are reading this summer

Photo: Barbara Alper/Getty

The summer is almost two-thirds over. What has been your favorite reading thus far — and what are you currently digging into? Here is ours.

Steve:

- Favorite thus far: "The Age of Surveillance Capitalism," Shoshana Zuboff (An uber-important book that I am recommending to everyone.)

- Reading now: "Neuromancer," William Gibson. (After a long, guilt-ridden period, I am finally in this sci-fi classic!)

- On deck: "1493," Charles Mann (How everything changed after Columbus.)

Erica:

- Favorite thus far: "The Glass Castle," Jeannette Walls (I was admittedly late to the party when I read this memoir earlier this summer. I've spent my whole life on the coast, and this took me to the heart of "left-behind" parts of the country.)

- Reading now: "These Truths," Jill Lepore (I started this last night after a glowing review from my boyfriend, who said, "It's all of U.S. history, but told like a story.")

- On deck: "Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber," Mike Isaac (The WSJ's John Carreyrou is calling this a must-read if you want to understand the modern Silicon Valley, so obviously I'm going to read it.)

Kaveh:

- Favorite thus far: "The Leavers," Lisa Ko (This moving novel was born from a 2009 deportation horror story, playing out across families and generations.)

- Reading now: "All the Light We Cannot See," Anthony Doerr (Just finished it Sunday. As good as promised.)

- On deck: "Rebooting AI," Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis (Marcus is a prominent skeptic of deep learning in AI, and this book argues for a new start in a field in a one-track obsession.)

4. Worthy of your time

The experimental setup. Photo: Sebastian Leuzinger/Auckland University of Technology

Google's AI work-around with the Pentagon (Lee Fang - The Intercept)

New Zealand's wondrous stump (Alison Snyder - Axios)

The hellish reality of hot-desking (Pilitia Clark - FT)

Crypto can't hide from the IRS (Laura Saunders, Britton O'Daly - WSJ)

The floating dairy farms of the Netherlands (Chase Purdy - Quartz)

5. 1 girl power thing: Saudi women go to work

On the way to work. Photo: Sean Gallup/Getty

About 23% of Saudi women have joined the workforce — a national record, Erica writes.

The big picture: While that's well below the international average of 48%, it's a sizable jump from the 18% of Saudi women who were working or looking for work in 2010, reports Quartz' Adam Rasmi.

- The backdrop: Over the last decade, the Saudi government has backed recruiting agencies that are placing women in jobs because it makes economic sense, Rasmi writes.

- In 2011, the government began offering unemployment aid, and although women are only 43% of the country's population, 80% of those applying for the assistance were women.

Sign up for Axios Future

Spot the mega-trends impacting our world