Axios Future

February 27, 2019

Have your friends signed up?

Any stories we should be chasing? Hit reply to this email or message me at [email protected]. Kaveh Waddell is at [email protected] and Erica Pandey at [email protected].

Okay, let's start with ...

1 big thing: Bowling and belonging

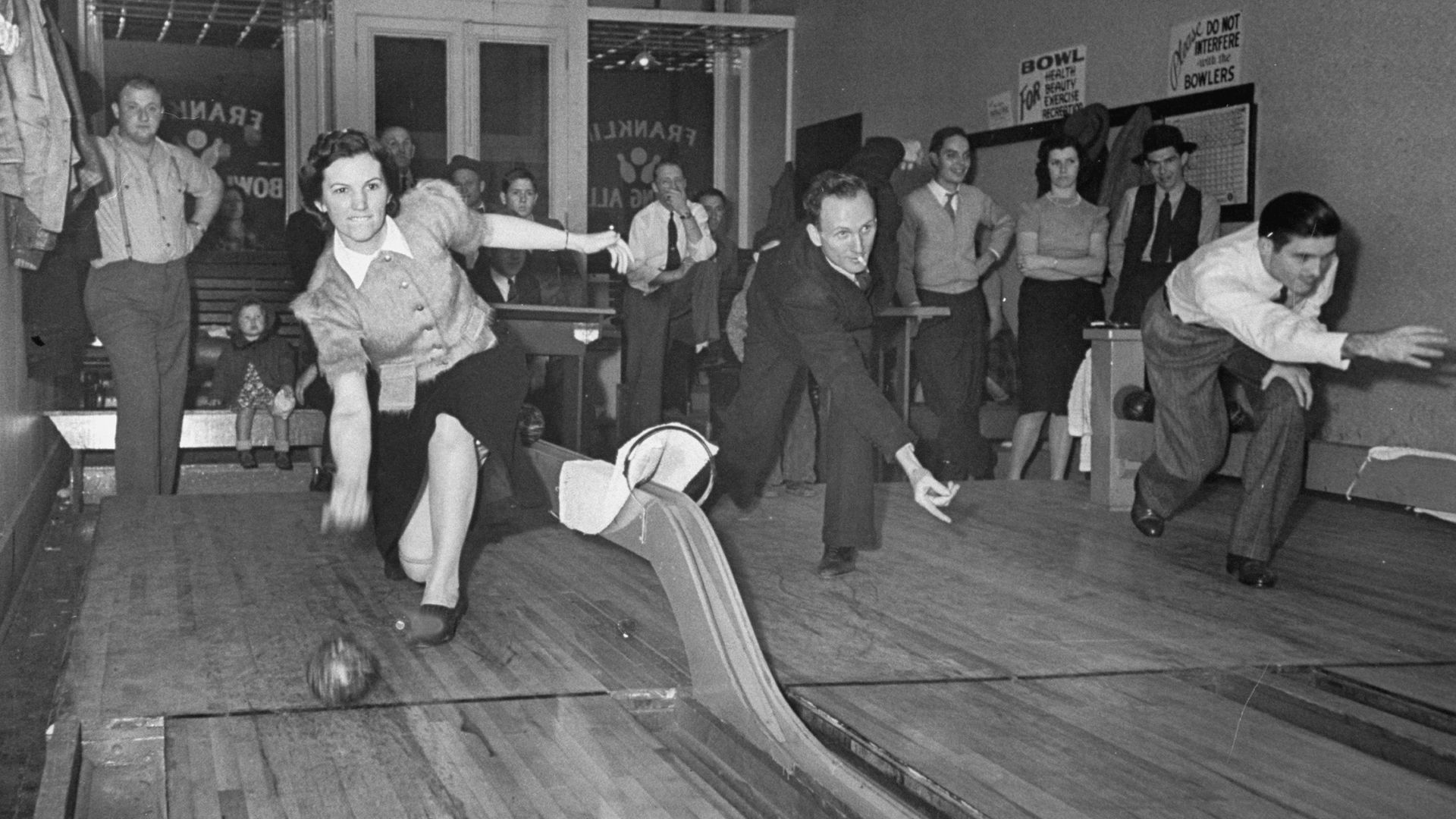

Belonging, 1941. Photo: Bernard Hoffman/LIFE/Getty

A seam running through the last three years of political turbulence is a loss of a sense of belonging — swaths of disoriented Americans and Europeans feel betrayed and under personal attack, and they are lashing out at institutions and leaders who they believe are responsible, or at least failing to do anything about it.

But that's only if you look at the public feeling toward the establishment "out there." If you ask about their own community, people are a lot more content. And what's making them so?

In a lot of cases, bowling.

What's happening: Public anger has been the most uniform signal from the raft of U.S. and European elections won by anti-establishment figures since 2016. As sociologists and other researchers have sought reasons why, a common answer has been a sense of loss of accustomed community and stature — a rising number of immigrants, a cratering of jobs from automation and the movement of factories abroad, and a feeling of siege by menacing outside forces.

As we've reported, a number of experts call this tribalism, a feeling of attack on a person's elemental identity. Now, CEOs and academics are looking for how to restore the lost sense of security:

- As Erica wrote, Walmart CEO Doug McMillon said earlier this month, "When someone walks into Walmart, I want them to feel, 'I belong here.'"

- In "The Future of Capitalism," British economist Paul Collier writes that people need a renewed sense of purpose. They lost the one many felt from World War II through the 1970s. Instead, the economic system has beaten them down.

- The problem, Collier argues, is that the advanced economies have truncated the lessons of Adam Smith, the father of capitalism. They have focused on the invisible hand — self-interest — and neglected their need to belong to a job or community. Capitalism fails, he writes, when it is "tainted by relying on the single drive of greed."

The upside of bowling:

While McMillon suggests the answer is more trips to Walmart and Collier a rehabilitated sense of purpose, Samuel Abrams, a professor at Sarah Lawrence College, calls for more visits to traditional local hangouts. Abrams spent three years conducting a survey of 2,411 people along with the American Enterprise Institute and the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

A major finding: If you want to create a sense of belonging, a bowling alley is a great place to start. "In bowling alleys, there is real interaction," Abrams says. "There is not texting. You are standing around doing something together."

This may sound superficial, but it's not, says Abrams. A study found a correlation between the presence of libraries or bowling alleys close to people's homes and their sense of community. And when they had that feeling, they tended to speak positively about their neighborhood.

- This is full circle from Robert Putnam's classic "Bowling Alone," which, as a metaphor for lost community, bemoaned a shrinkage in the number of bowling leagues.

But, but, but: A lot of people — perhaps lacking a nearby bowling alley — are still finding their anchor in partisan politics, according to Bruce Mehlman, a political lobbyist in Washington, D.C. "Politics increasingly fills the void previously served by rotary clubs and bowling leagues," he says, "with partisan tribalism replacing communitarianism."

2. A surprising factory

A Tempo Automation employee prepares a circuit board assembly machine. Photo: Kaveh Waddell/Axios

China and its neighbors dominate electronics manufacturing, a key part of Beijing's aggressive push to become the globe's tech leader.

Kaveh reports: But, in a surprising turn, a vital part of the lucrative industry has remained in the U.S.: boutique factories that build prototype circuit boards.

A buzzy example: Tempo Automation is pumping out small batches of circuit boards for top tech and defense companies — attracted by its partially automated assembly line — from a squat white building tucked beneath a highway in the warehouse district of San Francisco.

- Kaveh visited Tempo's factory, where he saw the company's play to modernize the cumbersome process by automating much of it.

Background: Before ordering up big shipments of circuit boards — the essential innards of nearly every electronic device — companies generally send out for a small set of prototypes to make sure everything works as it should.

- They can contract with a manufacturing giant in Asia, which is designed for huge orders and takes a long time to set up a new product, or they can go to a smaller manufacturer that specializes in prototypes.

- Both can be slow and vary in quality. This is a "big bottleneck" for tech companies, says Mark Thirsk, founder of Linx Consulting.

The fast pace of prototyping favors smaller shops located near the firms designing the boards over reigning electronics makers like Taiwan's Foxconn. So there are still several hundred quick-turn shops in the U.S., even while large-volume production has fled the U.S. and Europe entirely, says Jeff Doubrava of consulting firm Prismark.

Tempo's customers upload their plans and select parts on an online form. It works a bit like a car website that lets you choose color and options before spitting out an instant quote.

- For now, Tempo can build up to 250 boards at a time, and it can prepare orders in a day or two. Thirsk says Tempo's capabilities rival those of advanced manufacturers.

- Tempo makes boards for clients like NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Hitachi Metals and GE Life Sciences.

The factory floor was far from empty when Kaveh visited. Employees in white coats twiddled with imposing machines or typed at standing desks in a corner of the cavernous space. But only about a dozen people touch any individual order, says Ryan Saul, Tempo's VP of manufacturing.

Go deeper: Tempo Automation gets $20 million to make tech gear in pricey SF

3. Strangling newspapers

Commuting, 1955. Photo: Three Lions/Getty

For hundreds of local newspapers struggling across the country, the problem isn't Craigslist taking ad revenue or the internet taking readers — it's private equity ownership.

Erica writes: 882 U.S. newspapers are owned by 7 investment groups, reports the FT. And in many cases, the new owners are slashing the papers' budgets and staff.

In several states, the rise of private equity owners has correlated to a steep drop in newspaper circulations.

- New York: Circulation is down 59% between 2004 and 2018

- Colorado: 52%

- Michigan: 39%

- California: 38%

4. Worthy of your time

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

The secret lives of Facebook moderators in America (Casey Newton — The Verge)

The upside of tech you can’t afford (Ina Fried — Axios)

Hidden mechanisms that help the rich excel in elite jobs (Joe Pinsker — The Atlantic)

How New Orleans reduced its homeless population by 90% (Jeremy Hobson — WBUR)

Inside the secret sting to expose celebrity psychics (Jack Hitt — NYT)

5. 1 delay-of-game thing: Fish on second base

Screenshot: Yahoo Sports

In 2001, Diamondbacks pitcher Randy Johnson exploded a dove that flew between his screaming fastball and the catcher's mitt.

Kaveh writes: In 2019, where everything is weirder, a college baseball game in Jacksonville, Florida, was briefly delayed when it began raining fish, USA Today reports.

Well, just one. Here is how Jacksonville University's Twitter account described the incident:

FISH DELAY | An Osprey just flew over John Sessions [field] with a fish in his claws, but was threatened by a pursuing bald eagle, causing the osprey to drop the fish behind second base (Error). The fish was recovered by a [Jacksonville University] Dolphin and removed from the field.

Sign up for Axios Future

Spot the mega-trends impacting our world