Axios Future

March 21, 2020

Welcome to Axios Future, where I for one am just about out of ironic one-liners.

- Subscribe here if you haven't, and send feedback to [email protected] or hit reply.

📷 In this week’s must-see “Axios on HBO,” we dive into how the coronavirus pandemic is upending politics, business and global affairs. Don't miss:

- A rare, in-depth interview with China’s ambassador to the U.S. about the spread of COVID-19

- The CEO of Carnival Corp. defends its response to the Diamond Princess outbreak

- Microsoft's CEO on the remote work surge

- Sen. Ted Cruz talks about his time in self-quarantine (clip)

Tune in Sunday 6 p.m. ET/PT on all HBO platforms.

Today's issue is 1,603 words, a 6-minute read.

1 big thing: The coming health panopticon

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

COVID-19 became a pandemic because too many of the countries struck by the virus failed to detect and suppress outbreaks as fast as possible. But the coronavirus could usher in an era of intense health surveillance.

Why it matters: From location-detecting smartphones to facial recognition cameras, we have the potential to track the spread of disease in near real-time. But the public health benefits will need to be weighed against the loss of privacy.

Background: Epidemiologists can lay claim to being some of the first data scientists, going all the way back to John Snow discovering the source of a cholera epidemic in London in 1854. Today they use rapid contact tracing to track an outbreak from its source to its spread in an effort to contain it.

- But contact tracing is laborious detective work, requiring doctors to locate suspected patients and reconstruct their movements and contacts going back days.

- When a disease breaks out in the community — as COVID-19 is clearly doing in parts of the U.S. — that work becomes much more difficult, especially if testing continues to lag.

Modern technology, though, offers the potential to surveil exactly where people are and where they've been, through the location data on their smartphones and the trail of transactions they leave in their wake.

- China used data from state-run mobile carriers to locate people who had slipped out of quarantine during the worst stages of its COVID-19 outbreak.

- Major tech companies like Alibaba have developed apps that can classify people based on their travel history and risk of exposure to the virus.

- "In the era of big data and internet, the flow of each person can be clearly seen," epidemiologist Li Lanjuan told China's state broadcaster CCTV in February. "With such new technologies, we should make full use of them to find the source of infection and contain the source of infection."

In the U.S. and other Western countries, such efforts would likely face major ethical, legal and regulatory barriers, as my Axios colleague Scott Rosenberg wrote earlier this week.

- Those barriers are in place for a reason. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has come under fire for authorizing a plan to tap a secret collection of cellphone data to identify those who may have come into contact with the virus.

Yes, but: We are entering unprecedented territory with COVID-19. The fundamental challenge the U.S. faces in its response is a lack of data about who is sick and contagious and who isn't. Without that information, state and local governments have been forced to rely on blunt force tools of mass closures and social distancing that seem poised to kill the economy.

- There are less intrusive tracking tools that might help epidemiologists ahead of the outbreak, like Kinsa's internet-connected smart thermometers. By instantly gathering reports of fevers around the country, Kinsa can alert medical officials "so the system can respond before an outbreak becomes an epidemic," says the company's founder Inder Singh.

- As COVID-19 worsens, though, expect to see a greater willingness to trade privacy for effective health surveillance, just as 9/11 led to a tightening of security around airports and other public spaces.

"A situation like the pandemic creates a fundamental shift in how people react to technology. This is the direction we are going to be moving in."— Labhesh Patel, chief technology officer at Jumio, an ID verification company

The bottom line: We've already given up so much in the fight against COVID-19. Some elements of personal privacy may be the next to go. And don't expect the surveillance to end when the pandemic does.

2. Robotic supply chains for a post-pandemic world

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

The massive disruption caused by COVID-19 could lead companies to tap automation to manufacture products much closer to home.

Why it matters: The pandemic is revealing that the globalized supply chain that brings us many of our products is shockingly fragile. Easily programmable industrial robots could make it simpler to produce what we use here in the U.S., reducing that vulnerability.

Even before the novel coronavirus reached the U.S., the supply chain disruptions caused by the virus' spread in China were damaging the American economy.

- On Feb. 17, when there were just 15 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the U.S., Apple issued an earnings warning because of the impact of the virus on its Chinese suppliers.

- China made half the world's respiratory masks before COVID-19 hit and restricted exports once the pandemic was in full force, leaving other countries, including the U.S., with dwindling supplies.

Context: Obviously, the U.S. needs stronger domestic manufacturing capability, especially right now. But it's not just that American companies have grown dependent on international supply chains.

- As of last fall, U.S. manufacturers reported more than 500,000 unfilled jobs, due in large part to a gap between the skills companies needed and the skills workers had.

If workers aren't available, one option might be robots.

- Ready Robotics, a startup spun out of Johns Hopkins University, provides simple software to power industrial robots. The software allows workers with little to no experience in robotics to program industrial robots for manufacturing work.

- With robots that are more easily customizable, manufacturers can employ them for short and custom runs, mixing up what they can produce. "If you do it today, it takes 4 to 8 weeks of setup time," says Ben Gibbs, Ready Robotics CEO. "With our software, it's 4 to 8 hours for a run."

These changes were already underway before the pandemic, but COVID-19 may accelerate them.

- "The future of supply chain infrastructure will be focused on improving resiliency through onshoring and automation," says Rayfe Gaspar-Asaoka, a venture capitalist at Canaan. "It's the Zoom + Slack of manufacturing."

The bottom line: The first response in a pandemic is to stick close to home. That may prove true for manufacturing as well.

3. Remote work shift calls for fast footwork

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

Air CEO Shane Hegde last week sent an employee to the offices of a New York nonprofit to pick up more than 20 hard drives and upload their contents to the cloud to accommodate an abrupt shift to remote work, Axios’ Kia Kokalitcheva reports.

The big picture: Despite the popularity of cloud-based work tools, all kinds of sophisticated organizations ran into technological challenges when the spread of the coronavirus suddenly forced them to have employees work from home.

Between the lines: Many companies are set up to have some small portion of their employees working remotely at any given time, but few are prepared for all of them do so at once.

- One popular remote work tool is the virtual private network (or VPN), which lets employees log in to a company’s secure system without being at the office. But as Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince, whose company sells a cloud-based version of this tool, tells Axios, companies often don’t have these capabilities for all employees.

- He adds that a 100-person travel agency recently called Cloudflare because only five of its employees could use the VPN at one time but the agency needed to move everyone home immediately. Its outside IT vendor could come upgrade its equipment, but that would have taken two weeks, he says.

The bottom line: Many companies will likely rethink their policies on remote work, both culturally and technologically, after this crisis.

4. Geoengineering might work best in small doses

Photo: Kryssia Campos

A new study suggests solar geoengineering could work most effectively by trying to blunt half of expected global warming, rather than all of it.

Why it matters: Government policies to cut carbon emissions aren't on target to keep warming below dangerous levels, so geoengineering may eventually be necessary. By aiming for a more modest offset of the warming to come, researchers may be able to maximize the benefits while minimizing the risks.

How it works: Solar geoengineering involves trying to directly cool the climate by injecting aerosols into the atmosphere, which would reflect incoming sunlight.

Details: The new study, published in Environmental Research Letters, used computer models to conclude that putting enough aerosols into the stratosphere to cut expected warming in half appeared to hit the sweet spot of slowing climate change without inadvertently making it worse in some regions.

"When used at the right dose and alongside reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, stratospheric aerosol geoengineering could be useful for managing the impacts of climate change."— Peter Irvine, University College London, lead author

5. Worthy of your time

Hot zone in the heartland? (Elisabeth Eaves — Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists)

- A special report about the controversial opening of the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility, a high-containment disease lab, in the middle of Kansas.

There's one way we really are "at war" with the coronavirus (Matthew Zeitlin — Slate)

- A smart exploration of the one real parallel between World War II and our "war" against the coronavirus — the dire need to make and move lots of stuff.

History in a crisis — lessons for COVID-19 (David S. Jones — New England Journal of Medicine)

- What our past responses to epidemics can tell us about what's to come.

They went off the grid. They came back to the coronavirus. (Charlie Warzel — New York Times)

- Wish you could just forget the pandemic was happening? These rafters were off the grid on the Grand Canyon for 25 days and returned to a transformed world.

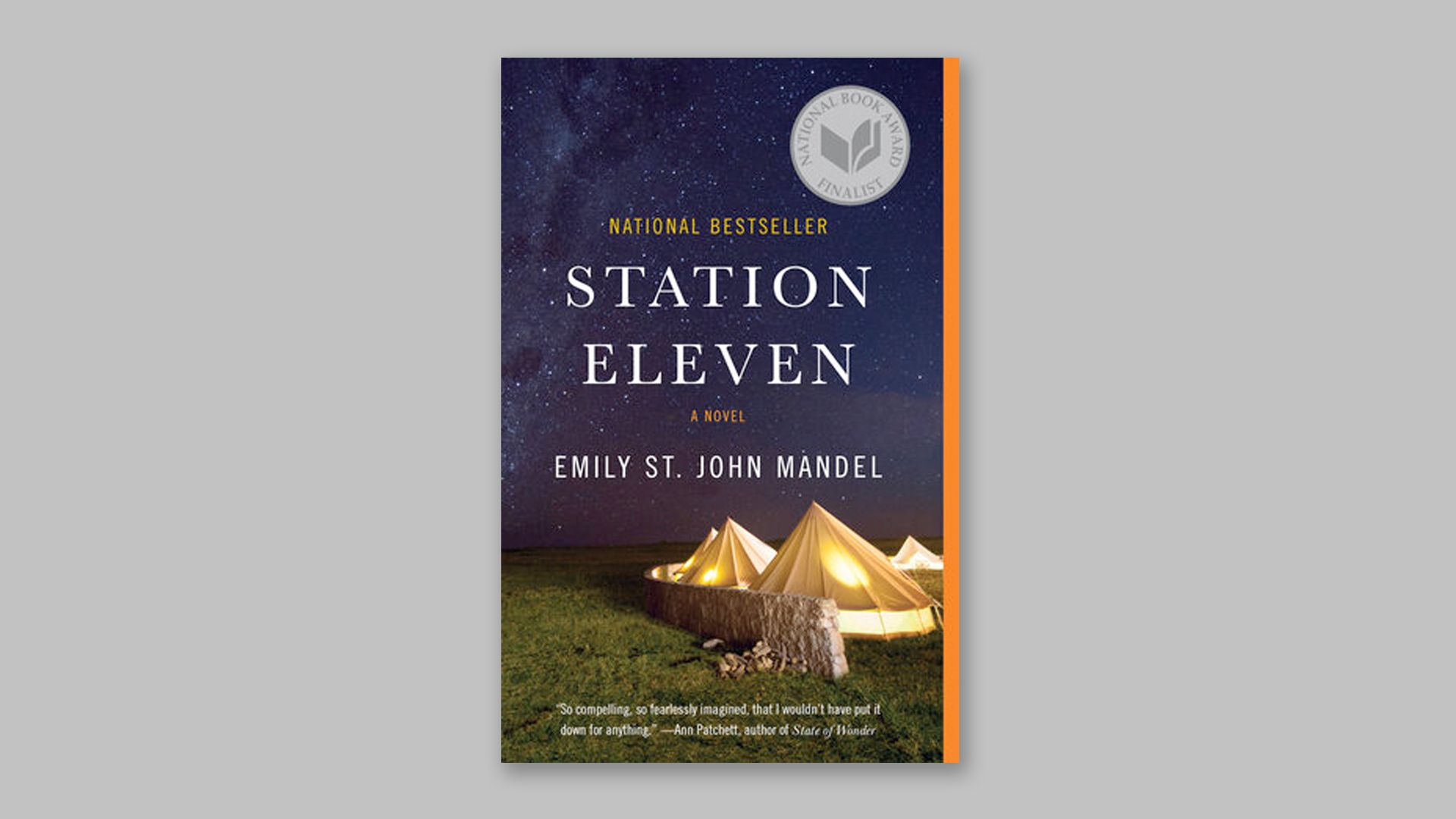

6. 1 sci-fi book: "Station Eleven"

Courtesy of Penguin Random House

Since we'll be home for the duration — a length of time that seems to be growing — this newsletter is recommending pop culture that jells with the themes of Future.

- This edition: the apocalyptic pandemic novel "Station Eleven."

Why you should read it: Sure, a novel about a superflu that kills nearly everyone on the planet and leads to near-total social collapse may hit a little too close to home these days, but "Station Eleven" is excellent — and even hopeful.

The novel, by Emily St. John Mandel, moves back and forth between the dawn of the swine flu pandemic and life among the few survivors 20 years later.

- Mandel is particularly brilliant at capturing both the sudden collapse that comes with the superflu and the eerie emptiness left in the wake of the virus.

- Survivors gather in small camps — including in an airport where flights in the air during the initial stages of the outbreak are forced to land — and live among the detritus of the modern world.

- Cars are refashioned to become horse-drawn carriages, while traveling troupes of amateur actors perform Shakespeare because, as one group's motto goes, "survival is insufficient."

The bottom line: Just surviving a pandemic — this one or a fictional one — isn't enough.

Sign up for Axios Future

Spot the mega-trends impacting our world