Axios AM Deep Dive

June 06, 2020

Good afternoon. Today's Axios AM Deep Dive is a top-to-bottom look at the collision of the two biggest stories in the world — systemic racial inequality and an ongoing pandemic.

Smart Brevity count: 1,437 words, or a 5-minute read.

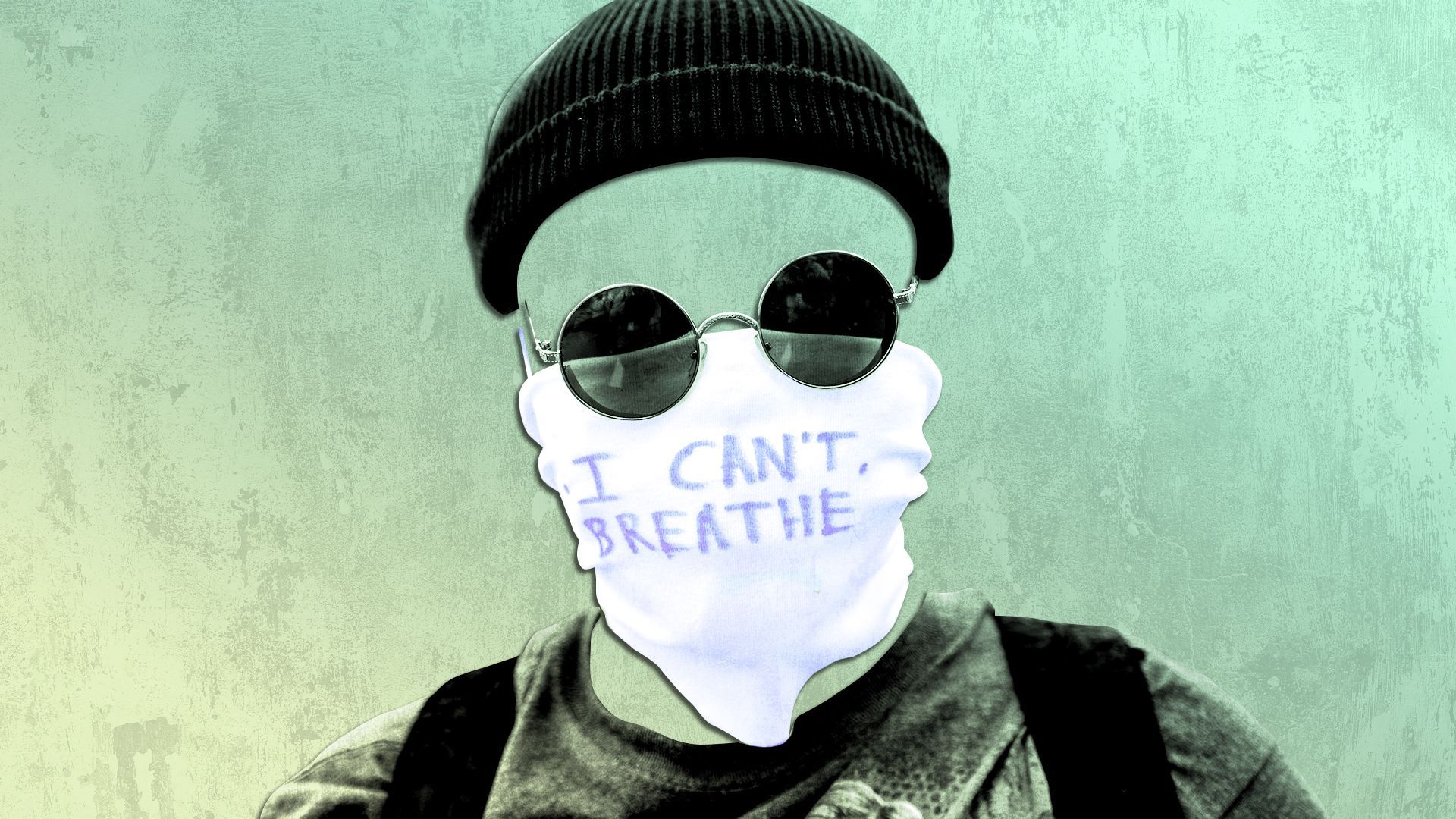

1 big thing: Why the coronavirus is killing more minorities

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios. Photo: Mark Makela/Getty Images

Christina Henderson — better known as Ms. Tina to the neighbors and volunteers who pass through the DC Dream Center — sees the statistics flash across her television about how the coronavirus is disproportionately hurting black people.

- But the reasons for that disparity, the underlying inequalities that the coronavirus has amplified, are nothing she needs to learn from the news.

- Ms. Tina sees it every day, as she dons a mask and gloves to serve meals to hundreds of people in her predominantly black D.C. community of Southeast D.C. She has seen it every day for decades.

- “To hear people and their fear, that is — that’s hard,” she told Axios' Caitlin Owens. “I’m 76 — I’ve dealt with this my entire life. No, I’m not surprised that they’re treated that way."

By the numbers: 75% of the people who have died from the coronavirus in D.C. were black. These deaths are disproportionately concentrated in the district’s poorest, blackest neighborhoods in Southeast D.C.

- In New York City, the death rate for black residents is 92.3 deaths per 100,000 people, for Latinos it's 74.3 per 100,000 people, and for whites it's 45.2 per 100,000 people. The same thing has played out in cities across the country.

These disparities reflect a slew of other, older inequities. Behind the shocked tone of so many headlines is a set of social and policy problems that are pretty familiar to health experts and even more familiar to the people they hurt.

- Minorities have higher rates of medical conditions that make them more vulnerable to death and severe infection if they catch the coronavirus, including heart disease, stroke, cancer, asthma, influenza and pneumonia, diabetes and AIDS.

- “When you go into the emergency room, you go into health care, black Americans do not get the same health care as white Americans,” Ms. Tina said.

- Social factors — including adequate housing, access to transportation, income, social supports and employment — have been shown to affect people's physical health, and now they're also risk factors for catching or spreading the virus.

2. The coronavirus economy is worse for black workers

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

Just as the pandemic hit communities of color more severely, the economic fallout is uneven, too, Axios' Courtenay Brown writes.

Why it matters: Recessions have historically been worse for black people than other groups — and the effects of the downturn will linger longer, even as the country recovers.

- The result is a persistent cycle of an economic second class and an example of the systemic racism that's sparked protests across the country.

The big picture: Since the government began tracking black unemployment in 1972, it‘s remained roughly twice as high as the rate for white workers — no matter the state of the economy.

- The pandemic narrowed the white-black unemployment gap to the closest it’s ever been. Still, black workers and other racial minorities are faring worse.

- This recession is particularly grueling for black workers, who have been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus. If they aren’t out of work, they are more likely to be in jobs that put them on the front lines of the virus.

- The pandemic also pushed the unemployment rate for Hispanics to the highest among all race/ethnic groups (17.6%) for the first time ever.

By the numbers: In May, the white unemployment rate fell 2 percentage points to 12.4% — a record monthly drop, per Reuters. For black people, the rate rose slightly to 16.8%. Asians also saw their unemployment rate jump to 15%.

What they're saying: The labor market is showing signs of recovery, but the economy is “leaving Black people behind again — this is true by gender & age," Olugbenga Ajilore, an economist at the Center for American Progress think tank, tweeted.

3. The trust gap

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios. Photo: Stanton Sharpe/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

A complex public undertaking like the coronavirus response depends a lot on public trust. But a legacy of systemic racism across multiple institutions has eroded that trust in many minority communities, Axios' Bob Herman writes.

Health care has its own sordid history, from the Tuskegee Study to hospitals' patient-dumping practices to substandard care for black mothers and babies.

- Consequently, minorities — especially black people — tend to trust health care providers less than white people do.

- In a Pew survey earlier this month, just 35% of black respondents said they had a great deal of trust in medical scientists, compared to 43% of white respondents. Pre-coronavirus surveys found similar results.

Between the lines: Researchers also have found that a negative experience with one institution, such as the police, often translates to distrust of another, such as health care.

- A robust system of testing, disease surveillance and isolation — the recipe to keep coronavirus infection rates at bay — requires a lot of buy-in from people who are wary of exactly that kind of undertaking.

- "How do you do contact tracing in communities that deeply mistrust medical institutions and now sort of are feeling like we're in the fight of our lives because of police brutality?" said Rachel Hardeman, a researcher at the University of Minnesota who studies racism and health equity.

The bottom line: Plans for successfully tracking and isolating to contain the spread of the virus cannot ignore the history of a health care system "that has never really valued [minorities] as a whole person," Hardeman said.

4. Poorer hospitals see more black patients

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

The inequalities in American health care extend right into the hospital: cash-strapped safety-net hospitals treat more people of color, while wealthier facilities treat more white patients, Bob writes.

Why it matters: Safety-net hospitals lack the money, equipment and other resources of their more affluent counterparts, which makes providing critical care more difficult and exacerbates disparities in health outcomes.

The big picture: A majority of patients who go to safety-net hospitals are black or Hispanic; 40% are either on Medicaid or uninsured.

The other side: Wealthy hospitals, including many prominent academic medical centers, are "far less likely to serve or treat black and low-income patients even though those patients may live in their backyards," said Arrianna Planey, an incoming health policy professor at the University of North Carolina.

- An investigation by the Boston Globe in 2017 found black people in Boston "are less likely to get care at several of the city’s elite hospitals than if you are white."

- The Cleveland Clinic has expanded into a global icon for health care, but rarely cares for those in the black neighborhoods that surround its campus, Dan Diamond of Politico reported in 2017.

The bottom line: Poor hospitals that treat minorities have had to rely on GoFundMe pages and beg for ventilators during the pandemic, while richer systems move ahead with new hospital construction plans.

Go deeper: The coronavirus is further dividing rich and poor hospitals

5. Cities see the problem — but they're broke

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

The pandemic's economic collapse is making it harder for local leaders to address the inequalities in their cities — just as the unrest over police violence has magnified the need for change even further.

The big picture: Evening out some of these disparities requires money, and city budgets are shot, Axios' Kim Hart writes.

What's happening: Tampa Mayor Jane Castor, the city's former police chief, said this week has been a "turning point in awareness" in her city.

- "Some individuals in some neighborhoods have never been in the low-income areas and are unaware of the problems and issues," she said. "This has broadened awareness of systemic issues and will foster community engagement."

- Tampa will still be able to fund existing plans for affordable housing, public transportation and a new effort on workforce development. But an anticipated $20 million budget shortfall will hamper new investments.

Cincinnati is dipping into reserves, furloughing employees and facing cuts to city services to deal with an $80 million budget deficit, said Mayor John Cranley.

- "We have the resources we need to get through it," he said. "But we need to be investing in public health, police and fire, economic empowerment, and small business loans to help people get back on their feet. We're not going to be able to do that."

Reality check: Many cities are struggling to marshal the resources to help residents recover from recent health and economic blows, let alone support new levels of community reinvestment.

6. "Why are we surprised?"

Screenshot: "Axios on HBO"

Robert Fullilove, an expert on public health at Columbia University, tells Axios' Dion Rabouin that racial disparities in health shouldn't surprise anyone because their causes are baked into multiple aspects of American society.

- "Let's just see racism as one of the ways that determines where you're gonna live and what kinds of conditions you're going to be exposed to," he said in an interview for "Axios on HBO."

- "If race is the factor that really dictates what kind of job you're gonna have, what kind of education you're gonna have to qualify you for some kind of employment, almost all the things that put you at a disadvantage — almost everything that's gonna put you on the margins of society — are also gonna be the set of things that put you at unique vulnerability and risk of being impacted by an epidemic, such as the one we're seeing right now."

"In a society where the quality of your health depends on how much money you can spend to assure your health, why are we surprised that folks with little money are also folks who are most likely to become sick? And then COVID-19 comes along."

Watch the full interview Monday at 11 pm ET, on all HBO platforms.

Sign up for Axios AM Deep Dive

A deeper look at the biggest topics impacting the future