Camp that imprisoned 7,000 Japanese Americans could soon be National Historic Site

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

A recreated guard tower at Amache, a former Japanese American incarceration camp, as seen in 2015. Photo: Russell Contreras

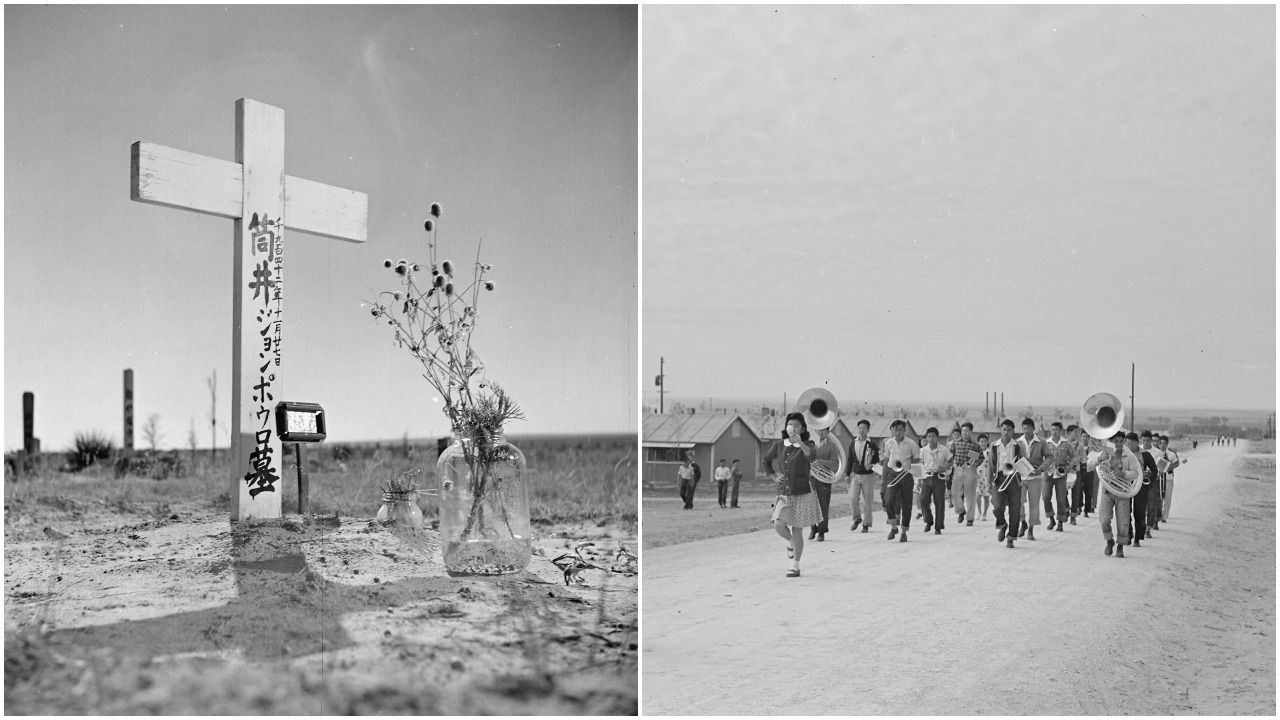

Guard towers with searchlights. Barbed wire stretching around the camp. Military jeeps that circled the perimeter. This is what survivors recall of Amache, the former incarceration camp in Granada, Colorado that imprisoned over 7,000 Japanese Americans during World War II.

Driving the news: Saturday marks the 80th anniversary of Franklin Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066 — which legalized the forced removal and mass incarceration of anyone with Japanese ancestry. Amache is now on the verge of becoming a national historical site, something survivors, descendants and advocates have campaigned for for years.

- The Amache National Historic Site Act, which cleared the Senate unanimously this week, would move ownership to the National Park Service and ensure it remains protected along with other incarcerations sites.

- Volunteers currently manage the preservation of the Amache grounds, but enshrining the area into a formal historical site would guarantee that the stories of those who were incarcerated are honored and preserved for future generations.

- The legislation awaits a final vote in the House, which passed an initial version 416-2.

The backdrop: In 1941, months before the Pearl Harbor bombing, Roosevelt commissioned Special Representative of the State Department Curtis B. Munson to gather intelligence on Japanese American disloyalty.

- Munson concluded that they posed very little threat — "There is no Japanese 'problem' on the Coast" — but Roosevelt and other U.S. leaders ignored the report amid rising anti-Japanese sentiment.

- Instead, between 1942 and 1945, the U.S. incarcerated nearly 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry in camps across the country, including the Amache site, also known as the Granada War Relocation Center.

In their words: "[W]e were forced from our homes, tagged like animals, and sent to the desolate prairie of southeast Colorado, where we lived in trauma, with a constant presence of armed guards, barbed wire, and suffering too large to describe in one correspondence," over 60 Amache survivors wrote in a January letter to the Senate.

- It was "like a prison," survivor Bob Fuchigami said in a 2017 interview with The Denver Post. "We were told not to go near the fence — you’d get shot."

- "You had to pledge allegiance every morning. Liberty and justice for all," Fuchigami added. "Obviously, it didn’t apply to us."

- Though Japanese Americans found ways to cope and regain some semblance of life behind the barbed wire, they never forgot why they were there.

- "The assumption was: You’re guilty," Fuchigami told the Post. "You haven’t done anything, but you might do something, or you will do something."

- And the damage was lasting. "Many grew up feeling ashamed of our Japanese ancestry," Amache survivor and former Congressman Mike Honda wrote in 2015.

What they're saying: "Our nation still has a long way to go to learn from this mistake, and our community—both old and young—continues to suffer from anti-Asian hate crimes," the survivors wrote in their letter to the Senate.

- "Adding Amache to the National Park System would allow us to protect a physical, and sacred, reminder" of the impact of Japanese American incarceration.

- They all feel the urgency, Jon Tonai, whose father was imprisoned at Amache, told Axios. "It's for our grandparents and for our parents, for them to be able to tell their story," Tonai said. "For each day that passes and we lose another [survivor], that's one day too late."