A new kind of propulsion could aid in space exploration

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

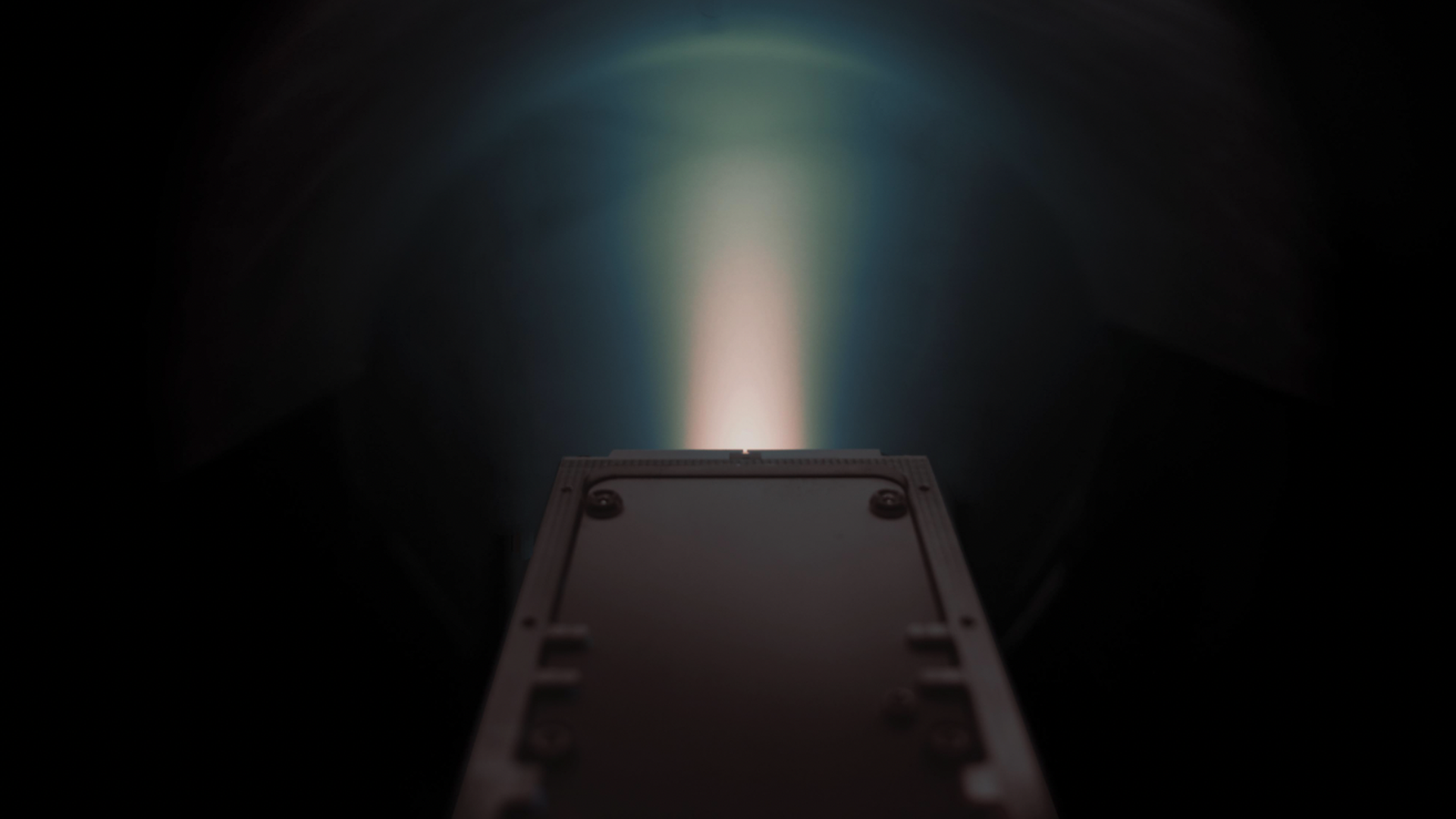

A view of the flight model of the thruster. Photo: ThrustMe

A new kind of fuel for small satellites was successfully tested in space for the first time.

Why it matters: Iodine electric propulsion could enable new ways for tiny satellites to explore the solar system and allow spacecraft to avoid collisions in orbit, according to ThrustMe, the company behind the technology.

- Analysts predict thousands of new small satellites could launch to space in the coming years, and engineers are looking for efficient and less expensive ways to maneuver them in orbit and keep them out of the way of harmful space debris or other satellites.

What's happening: The iodine-fueled thruster — called NPT30-I2 — was launched aboard the Beihangkongshi-1 satellite sent to space by China's Long March 6 rocket in November 2020.

- A new study from Nature detailing the mission suggests the novel thruster could act as an alternative for satellite companies looking to diversify the types of fuel they use in the future.

- "In parallel with our in-space testing we have developed new solutions allowing increased performance and have commenced an extensive ground-based endurance testing campaign to further push the limits of this new technology," Dmytro Rafalskyi, CTO and co-founder of ThrustMe, said in a statement.

Context: Thrusters for small satellites typically run on xenon, a relatively rare and expensive gas that's not easy to produce.

- Iodine-based propulsion is cheaper and the fuel is easier to work with than xenon, Rafalskyi added.

- The new type of propulsion can also be used in a relatively small thruster, which is key for little satellites where every gram of weight counts toward performance.

Yes, but: "Iodine is highly corrosive, presenting a potential danger to electronics and other satellite subsystems — Rafalskyi and co-workers had to use ceramics and polymers to protect the metal components of their system," Igor Levchenko and Kateryna Bazaka, two researchers who weren't involved in the study, wrote in a commentary.

- They also pointed out it takes about 10 minutes for the iodine to heat up, meaning it might be hard to maneuver satellites using the thruster in time if a quick-turnaround emergency occurs.

Go deeper: Russian anti-satellite test reveals dangers of space junk