Urban landscaping to blame in prolonged, crippling allergy season

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

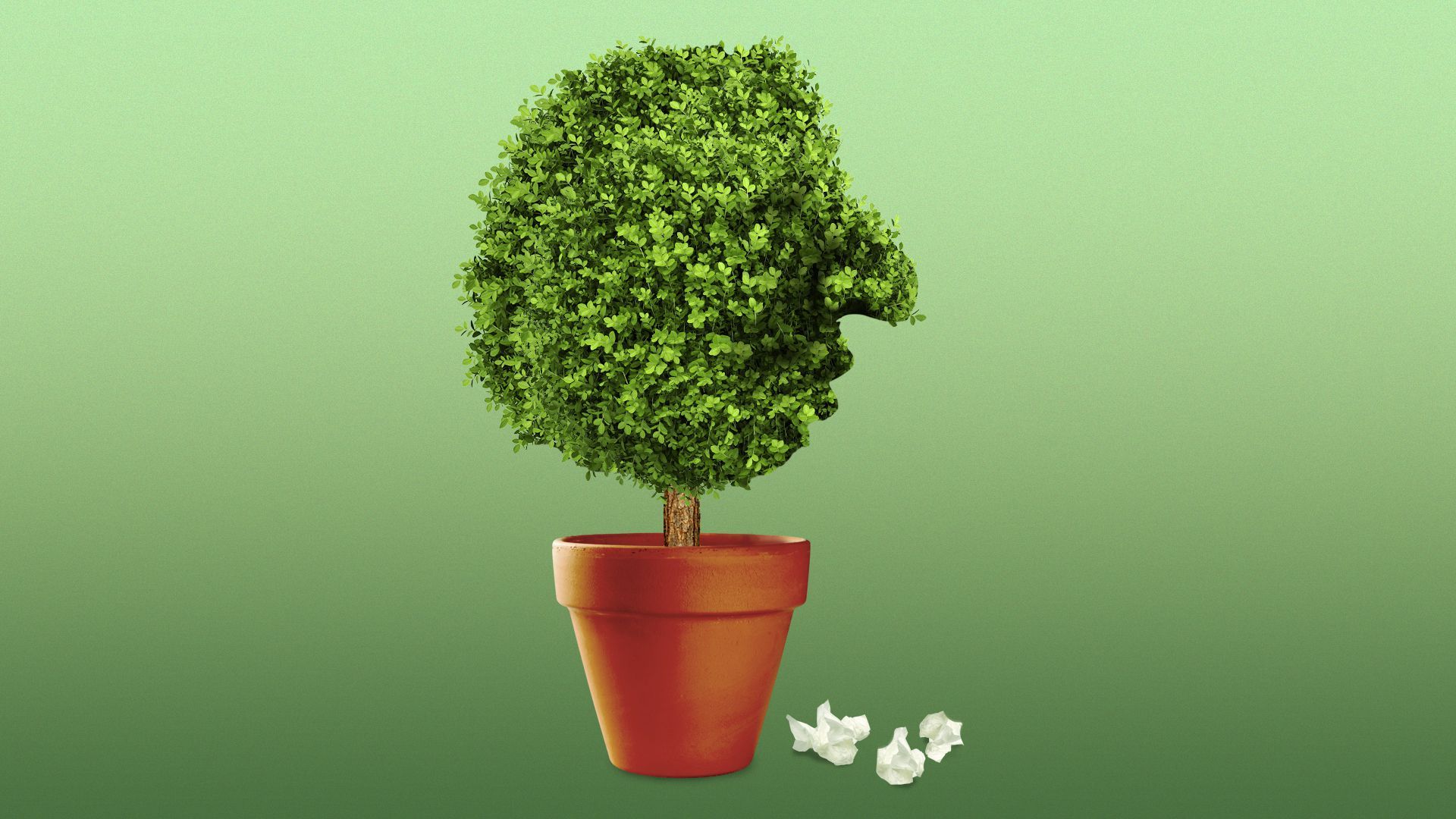

Illustration: Shoshana Gordon/Axios

Allergy season in North America has been the lengthiest and the most severe in decades, and experts say the millions of disproportionately male trees planted in urban areas are partly to blame for high pollen counts.

Why it matters: Prolonged exposure to pollen is disrupting the lives of an increasing number of people who are developing allergies that can lead to lifelong treatments for respiratory problems.

Threat level: Pollen counts are greatly affected by the “botanical sexism” found in urban landscaping, horticulturist Tom Ogren tells Axios. Trees that have male reproductive organs are preferred in areas because they don't drop messy seed pods or fruit, but instead release pollen certain times during the year.

- When female trees, which capture pollen, are nearly non-existent, landscaped areas can be overrun by mass amounts of pollen in the air.

- "It's alarming to me because if we don't start to get a handle on this pretty soon the air in our cities will be unbreathable," Ogren said.

What's happening: Immediate symptoms of tree pollen allergies include rhinitis, conjunctivitis, hay fever, allergic-asthma, dermatitis and even anaphylactic shock.

- Longer term, it could lead to the need to treat asthma, chronic sinusitis, upper respiratory infection, nasal congestion or sleep-disordered breathing.

- More than 300 million people have asthma globally, and that number is expected to rise by 100 million by 2025.

The big picture: Pollen season has increased by 20 days annually between 1990 and 2018, while pollen concentrations in North America increased 21% over the same time period, a recent study found.

- A study published last month found male trees and shrubs studied as early as 1998 have inundated cities and contributed to overall allergy index in the U.S. by about 6%, with increases as great as 20% in Casper, Wyoming, and by nearly 15% in Minneapolis.

- Only 8% of forests in 38 U.S. cities and nine international cities were rated "low" for allergies, while more than 51% and about 40% of cities had medium and high allergy scores, respectively, as of 2018 and per the U.S. Department of Agriculture's urban forestry service.

- Warming temperatures and extreme weather due to climate change, pollution and excess carbon dioxide in the air have exacerbated this issue by lengthening the pollen-producing season.

What to watch: For years, advocates, allergist associations and the federal government have been recommending decreasing the number of male trees and increasing female trees, which would reduce community pollen exposure.

- Some cities like Albuquerque and Berkeley have made pledges or created pollen control ordinances that require a better ratio in male-to-female planting or only require female trees.