The cicadas are a preview of a buggy future

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

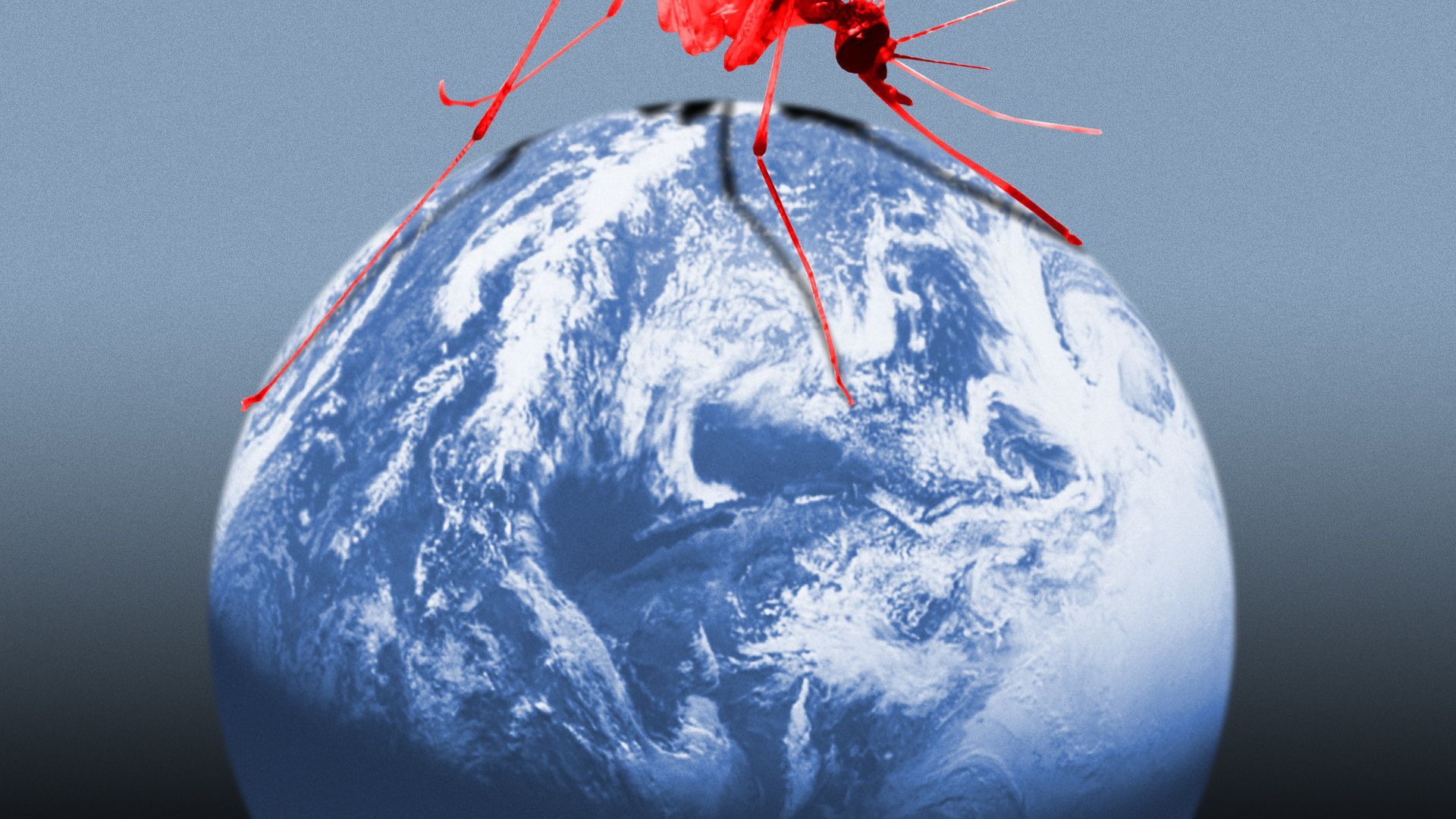

Illustration: Annelise Capossela/Axios

Trillions of Brood X cicadas are now emerging throughout parts of the mid-Atlantic and Midwestern U.S.

Why it matters: Most immediately, because they can be as loud as a Metallica show when they're singing in concert.

- But the behavior of cicadas will provide important clues to how climate change and human influence are altering the environment, and preview a future where some insects — including many of the species that most threaten us — could swarm in ever greater numbers.

By the numbers: As soil temperatures 8 inches underground reach 64°F, it will signal to cicadas of Brood X that it is time to end their 17 years underground and burst through the forest floors and suburban lawns of their native territory.

- Beyond their clockwork periodicity — which some scientists believe evolved during ancient glacial periods — Brood X cicadas have two things going for them: size and sound.

- As a mass, Brood X cicadas emerge in such numbers that as many as 1.5 million can be found in a single acre, which helps enough of them survive predators during their four- to six-week lifecycle to mate, lay hundreds of eggs and start the whole process over again.

- To attract those mates, male cicadas produce sound via the tymbals on either side of their abdomens. When masses of cicadas in a small area all sing at once, the volume can be higher than 85 decibels — loud enough to potentially damage hearing over a prolonged period.

Aside from the annoying noise and the ick factor, cicadas pose no threat to human beings. But the reverse isn't necessarily true.

- Periodical cicadas thrive in forest edges, but they need trees to reproduce, which makes wider-scale deforestation a threat, one that's already taken a toll on other periodic cicada broods.

- Because cicadas are dependent on temperature cues to know when to emerge en masse, climate change can mess with their life cycle. Cicadas that emerge off-cycle are known as "stragglers," and there's evidence that some members of Brood X emerged years early, which puts them at greater risk from predators.

The big picture: Climate change and habitat loss have already been implicated in the decline of countless other insects, from wild bees to monarch butterflies to certain kinds of moths. But other insect species will thrive in a warmer world — to the detriment of the rest of us.

- While honeybees have been under well-publicized stress, beekeepers have been able to curb losses in recent years. But that's less true for native pollinators, which have suffered as their native habitat has been replaced by sterile lawns.

- In general, though, as temperatures rise, insect metabolism and reproduction rates speed up, which means more insects eating more.

- One recent climate model predicted that as a result, the crop yield lost to pest insects could increase 10–25% for every additional 1.8°F degree of warming.

- A 2019 study predicted that under the most extreme warming scenarios, an additional 1 billion people around the world could face their first exposure to a host of mosquito-borne illnesses like dengue fever and Zika, as hotter temperatures allow the insects to expand their geographic range.

- Suburban development in partially forested areas — as well as climate change — is increasing the threat from tick-borne diseases, with the number of counties in the Northeast and upper Midwest considered at high risk of Lyme disease increasing by more than 300% between 1992 and 2012.

The catch: Connecting climate change to insect-borne disease is tricky, in part because rising incidences of diseases like Lyme likely also reflect greater awareness and more meticulous tracking.

- Even with warmer temperatures, the spread of insect-borne diseases like Zika is still primarily a function of poverty. Yellow fever was once prevalent in the U.S. as far north as Boston, and the CDC's location in Atlanta is due to the fact that the agency's initial focus was the control of malaria, which was endemic through much of the South until the postwar era.

What's next: This month, British biotech company Oxitec launched the first field trial in the Florida Keys of mosquitoes that had been genetically modified to curb population growth and limit the transmission of disease.

- MIT geneticist Kevin Esvelt has suggested genetically editing white-footed mice to be resistant to Lyme, which would potentially disrupt the chain of transmission to human beings.

- In both cases, though, some experts worry about unknown side effects that could come with releasing modified animals into the wild.

The bottom line: Cicadas are a loud, if temporary nuisance, but more dangerous bugs aren't going anywhere.