Why we struggle with the election expectations game

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

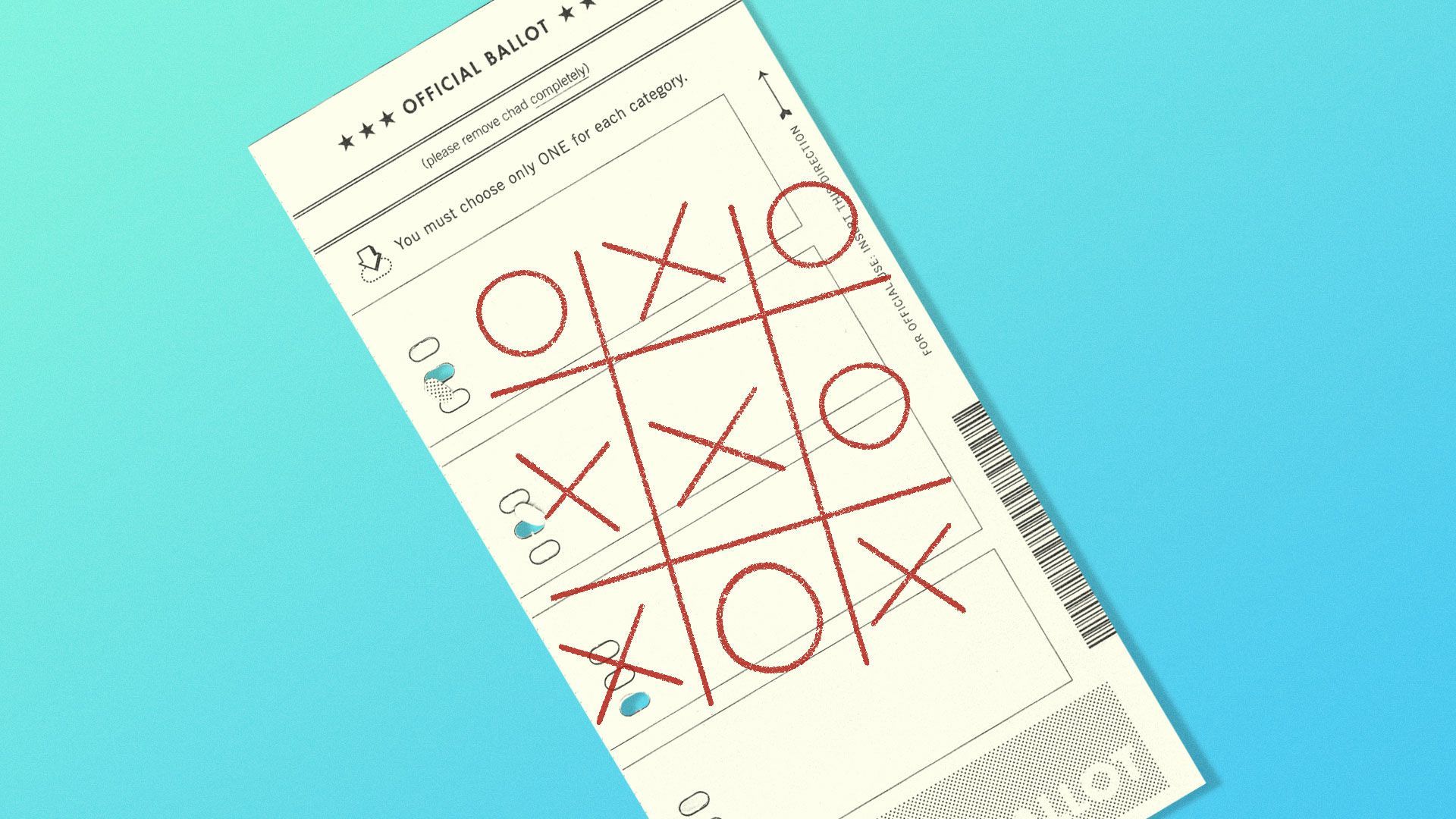

Illustration: Eniola Odetunde/Axios

Joe Biden appears close to an electoral win that will likely be narrower than election forecasts projected, and the initial sense that he underperformed expectations, which were themselves off base, could color his election and perhaps his presidency.

The big picture: We can't help but judge events based on whether they exceed or fall short of our expectations for them — but those expectations often aren't grounded in reality.

While the polling industry will sift through the reasons it missed how close the Electoral College fight ultimately was this year, it's vital to keep in mind that our shifting perception of what happened in the election is being shaped by the prior expectations formed by those polls and the order in which information about the vote has come in.

- Scientists have long known that our expectations about future events influence how we perceive those events when they occur, even on a neurological level.

Driving the news: President Trump has complained that polls projecting a Blue Wave this year equate to a form of voter suppression that kept his supporters home, but the number of votes cast this year gives no support for that argument.

- Voter turnout this year could end up being the highest since 1900, so there's not much evidence that the forecasts kept Trump's or Biden's supporters at home.

- Yet the fact that Biden seemed to be coming in below those forecasts — especially at first — likely shaped the early perceptions of the election.

The backstory: A 2020 paper found that election forecasts — which can translate what appear to be small polling gaps between candidates into fairly large probabilities that one will ultimately win — are often badly mischaracterized by the public.

- One-third of study subjects in the paper thought a candidate with an 80% chance of winning had the support of 80% of voters — which is very much not the case.

- Forecasts that Hillary Clinton was far more likely to win the 2016 election may have shaped coverage of the race as well as decisions by key officials like then-FBI Director James Comey, and could have led many of her supporters to skip voting, according to the study.

But, but, but: "If the polls are wrong, they never described reality, and there is no divergence to explain," the political writer Ezra Klein tweeted. "The map being wrong isn't a mistake of the terrain."

- The American voting population — at least in terms of electoral votes — was simply closer and more divided than we expected. Had the map been correct, we wouldn't have been surprised by a nail-biter.

Be smart: The unique nature of the 2020 election — conducted during a pandemic, with a record-breaking number of mail-in ballots — also wreaked havoc on our perceptions.

- Because different states reported results at different times — in part because battleground states like Pennsylvania were not permitted to begin counting mail-in ballots until Election Day — it appeared as if Trump had built a lead that Biden then whittled down over time.

- But remember: the votes existed before they could be counted. What appeared to be Biden "catching up" was just an illusion created by the order in which different votes were counted, albeit an illusion that helped shape how we viewed the election, as some polling experts noted.

The bottom line: Given how problems in polling are making it difficult to really know what the American electorate is thinking, we would be smart to approach the next election — and this one, as the final votes are tabulated — with a little more humility.