Countries put their populations first in scramble for COVID vaccines

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

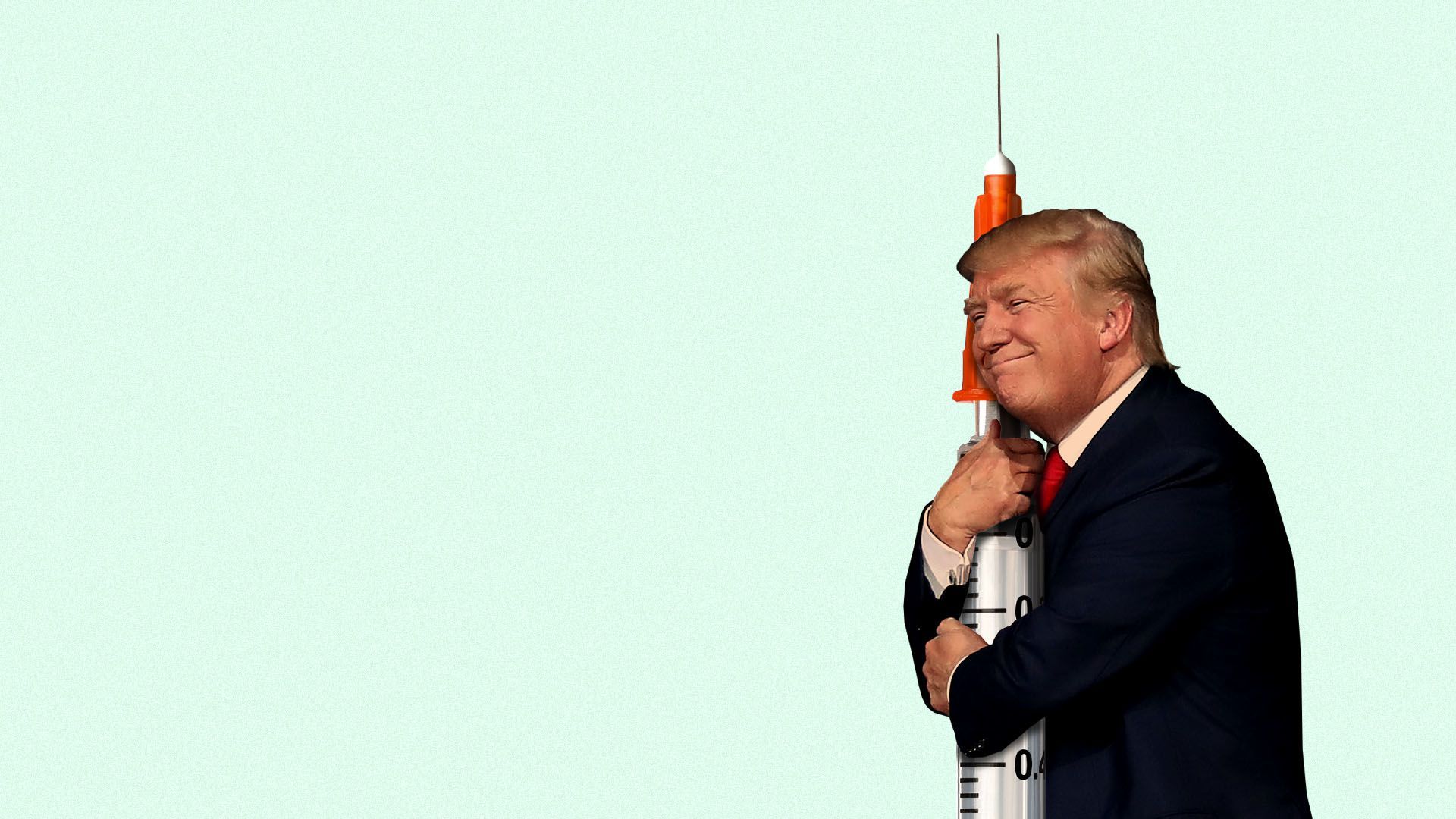

Photo Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios. Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The race is on to test and produce billions of doses of the myriad coronavirus vaccines currently in development — and to determine how they will be distributed if approved for use.

Take three pieces of news from the last 48 hours.

- The Chinese government revealed it began an experimental program in late July to vaccinate high-risk groups. President Trump is reportedly anxious to announce similar emergency authorizations soon.

- 172 countries (but not China or the U.S.) have submitted “expressions of interest” in the COVAX initiative, which aims to distribute vaccines globally according to need, rather than wealth.

- A new poll found that two-thirds of Americans believe vaccines developed in the U.S. should only be made available abroad after all domestic needs are met.

The big picture: It’s increasingly clear that a minority of the global population — likely only a tiny sliver — will be able to obtain a vaccine in the near term.

- First in line are people in countries that produce vaccines or can afford to buy them at scale — ahead of, say, health workers or the elderly elsewhere around the world.

- As international organizations scale up their efforts to change that dynamic, governments are busy buying up doses for their own populations.

State of play: The U.S. has helped fund the research behind several leading vaccine candidates, and has purchased a combined 800 million doses of six vaccines, with the option to buy 1 billion more, per Nature.

- The Trump administration has compared its approach to that of an airplane passenger securing their oxygen mask before helping others, Thomas Bollyky and Chad Bown write in Foreign Affairs.

- “The major difference, of course, is that airplane oxygen masks do not drop only in first class,” they write.

The U.K. has also purchased a first-class ticket — 340 million doses for a population of 67 million.

- That may sound excessive, but the U.K. has (like the U.S.) hedged its bets between several vaccine candidates, most of which require two shots.

And while the EU has led calls for equitable global distribution, the bloc has simultaneously secured hundreds of millions of doses for its members.

- Japan has placed large purchase orders, as have countries like Indonesia and Brazil that have less cash to spend but are wary of being left out.

Breaking it down: 2.4 billion doses of one still-to-be-approved vaccine, from Oxford University and AstraZeneca, are already scheduled for delivery by the end of 2021.

- While most of the leading vaccines are slated for production in the U.S. and Europe, the Serum Institute of India — the world's highest-capacity vaccine manufacturer — says it will produce upward of 1 billion doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine by next summer.

- The institute's CEO says half of those will be distributed domestically, but India’s government is likely to demand even more.

China, meanwhile, has three vaccines in phase III human trials and many more in development, and it says it will treat any successful vaccine as a global “public good.”

- Most analysts expect Beijing to prioritize its domestic population, though the promise of a vaccine is a useful geopolitical tool.

- Russia is also attempting to position itself as a global supplier, though it’s unclear whether Moscow has a backup plan if the vaccine it has fast-tracked doesn't prove to be safe and effective.

The flipside: The clearest alternative to a world in which vaccines are hoarded by a few countries at the expense of the others is the COVAX initiative, from the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the Gavi vaccine alliance and the World Health Organization.

How it works: A "portfolio" of nine vaccine candidates (including the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine) receive investment from COVAX, which will distribute any that are approved to both high- and low-income countries.

- Distribution will be based on population size, with health care workers and vulnerable people prioritized and a portion kept in reserve to be deployed to hot spots.

- The groups behind COVAX are aiming to avoid a higher-stakes repeat of the 2009 H1N1 vaccine, which was secured almost entirely by rich countries.

Between the lines: The incentives are clear for poor countries, but perhaps less so for the rich ones that would effectively subsidize their access.

- Gavi CEO Seth Berkley argues that, in fact, it's a "win-win" for rich countries: "Not only will you be guaranteed access to the world’s largest portfolio of vaccines, you will also be negotiating as part of a global consortium, bringing down prices and ensuring truly global access."

- Some higher-income countries — including Japan and the U.K. — have expressed interest in COVAX while also cutting deals directly with vaccine manufacturers.

- Given the limits on global manufacturing capacity, those deals could undermine the effectiveness of the global initiative.

What to watch: COVAX hopes to distribute 2 billion doses by the end of next year, though it will need significantly more funding than it has currently secured.

- There are at least two notable absences on the list of 172 interested countries: the U.S. and China.