Why the world map froze

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

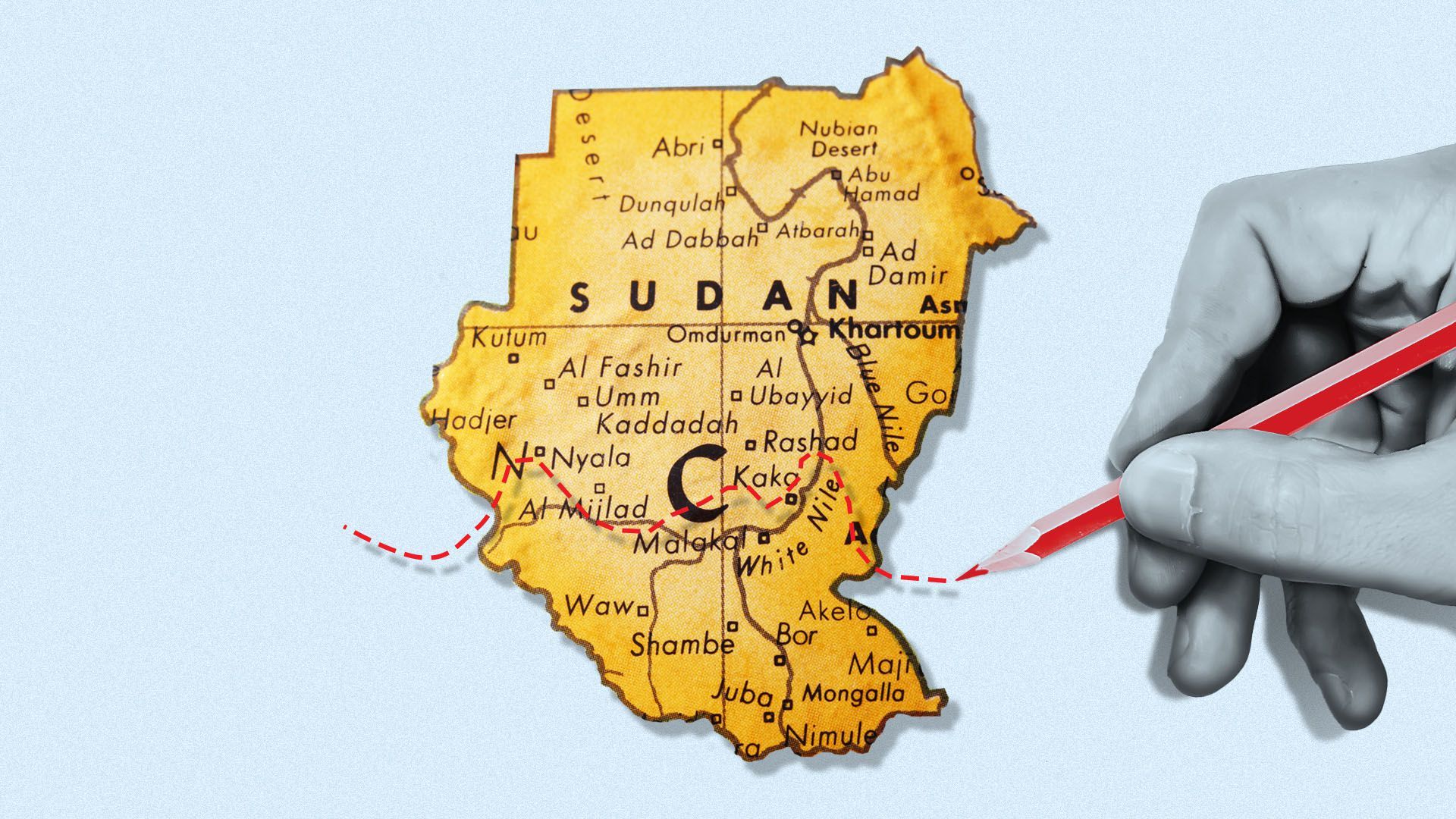

This sort of thing used to happen much more often. Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

This week marks nine years since South Sudan was admitted to the United Nations, becoming the 193rd and most recent entrant into the club of internationally recognized countries.

The big picture: This is the longest period in modern history during which the world map has remained unchanged.

- Simply relabeling three small countries — Cape Verde to Cabo Verde, Swaziland to Eswatini, Macedonia to North Macedonia — would bring a world map from Barack Obama’s first term up to date.

By the numbers: The UN added 44 members (most of them newly independent African nations) in the 1960s, 26 in the 1970s, seven in the 1980s, and 26 in the early 1990s as the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia fractured.

- Since 1995, there have been five island countries — Tonga, Kiribati, Nauru (all 1999), Tuvalu (2000) and Timor-Leste (2002) — added to the UN roster, while Serbia and Montenegro split in two in 2006.

- In the 2010s, South Sudan stands alone. The young country’s tumultuous history seems to reinforce the view that new countries will be inherently fragile.

How it happened: In his 2018 book “Invisible Countries,” Josh Keating writes that we're living through a period of “cartographical stasis," unique in history.

- “When I was growing up — late '80s, early '90s — it seemed like new countries were being created all the time,” Keating told Axios in an interview.

- “If you look back at international relations scholarship at that time, there was sort of an assumption that that would keep going. That self-determination movements would just keep succeeding and the world would keep being carved up into smaller and smaller national units.”

- Instead, the world’s borders — many of them drawn by colonial powers and maintained after independence — have locked into place.

Existing states and multilateral institutions nearly always oppose border changes and separatist movements.

- Even when there’s little chance of warfare or ethnic cleansing — as in Scotland or Catalonia, for example — the world tends to line up behind the status quo.

- Other recent movements toward statehood, as in Iraqi Kurdistan, have stalled.

- We're seeing fewer fights for independence, Keating says, and more movements for greater autonomy at a subnational level, as in Ethiopia.

The flipside: By fueling frozen conflicts and annexing Crimea, Vladimir Putin's Russia has proved a glaring exception in this age of immovable borders.

- But elsewhere, rising nationalism has expressed itself not as "a challenge to existing borders" but an effort "to build those borders up and keep the rest of the world out," Keating says.

What to watch: The UN could gain a new member if Kosovo — already recognized by around 100 countries — ever reaches a deal with Serbia.

- Tensions over Taiwan's status are also increasing, with the U.S. redoubling its support to the self-ruling island as China threatens reunification, by force if necessary.

- Palestinian statehood continues to be debated and to move no further than that.

The bottom line: “I don’t see any candidates for independence on the horizon," Keating says.