A new way to rapidly diagnose disease

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

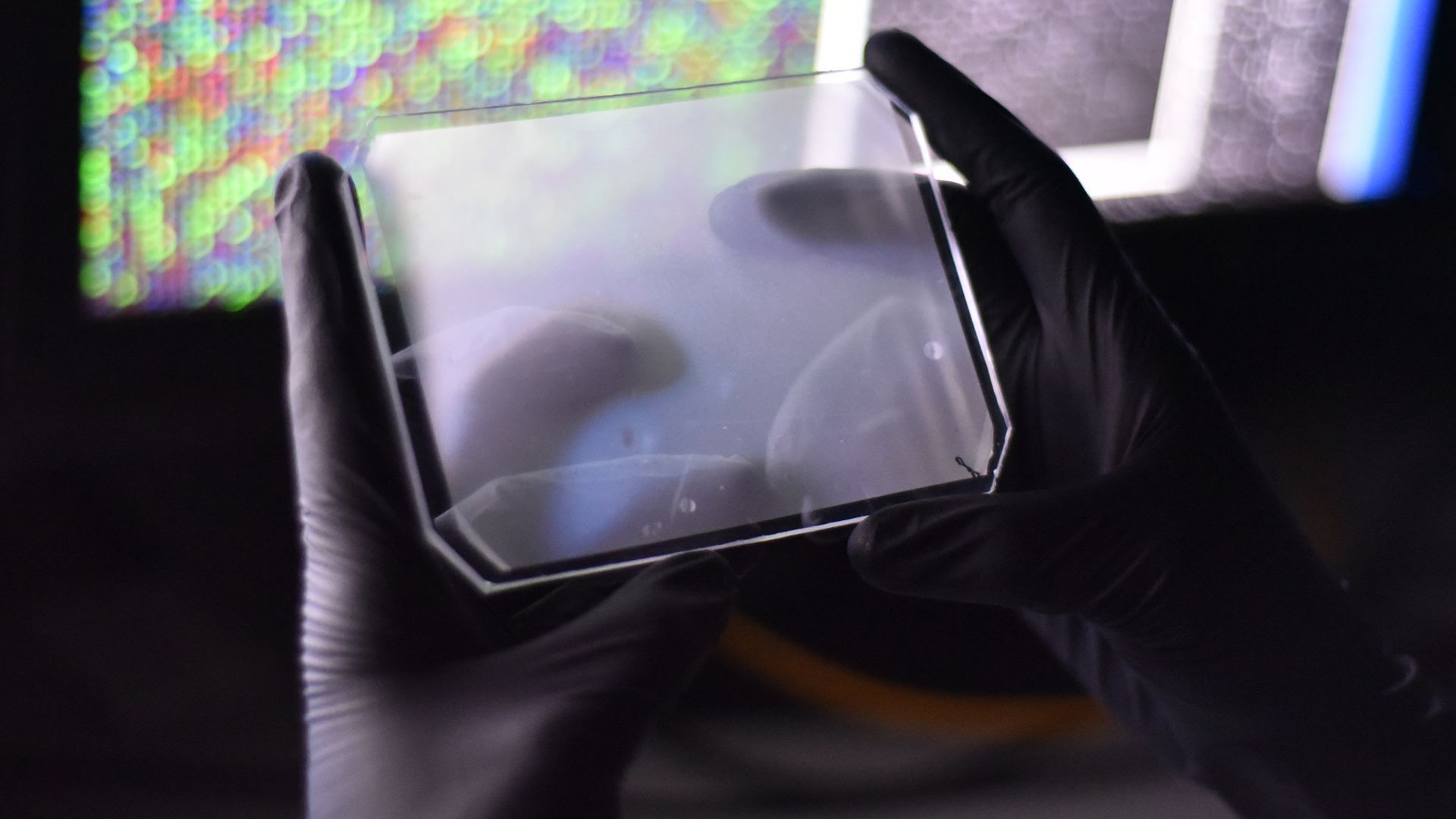

The Broad Institute's microwell CARMEN chip. Photo: Michael James Butts

A new technology has been developed using CRISPR-based molecular diagnostics to run thousands of tests for diseases simultaneously, per a paper published in Nature today.

Why it matters: COVID-19 has painfully demonstrated the limits of conventional diagnostics methods for infectious disease. A new platform that would allow doctors to test a single sample for thousands of different pathogens could revolutionize disease response.

The new testing platform, called CARMEN and developed by scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, provides one possible answer to a question that often bedevils doctors: What are sick patients actually infected with?

- Doctors often generally treat people who present with respiratory disease symptoms first, and then find out the cause later — or often, never.

How it works: The Broad Institute's new test uses rubber chips slightly larger than a smartphone, each with tens of thousands of "microwells" — compartments that hold two tiny droplets. One droplet contains viral genetic material from a sample, while the other contains virus-detection reagents.

- When the detection droplet, which includes the CRISPR protein Cas13, finds the specific viral genetic sequence being targeted — like the novel coronavirus — it produces a detectable signal. The entire process can yield results in eight hours.

What they're saying: The new technology could help speed COVID-19 tests, but its bigger impact could be in enabling clinicians to rapidly test a patient sample for more than 150 different viruses.

- "Imagine a world in which you go to the doctor and you actually find out what's making you sick," Cheri Ackerman, a postdoctoral student at the Broad Institute and lead author of the paper, said on a press call. "Instead of epidemiologists wondering what's circulating in a community, they'd be able to have accurate statistics of what's spreading and where."

Editor's note: This story has been corrected to reflect that Cheri Ackerman was quoted not Catherine Freije.