3D printing can help, but won't solve, the coronavirus equipment shortage

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

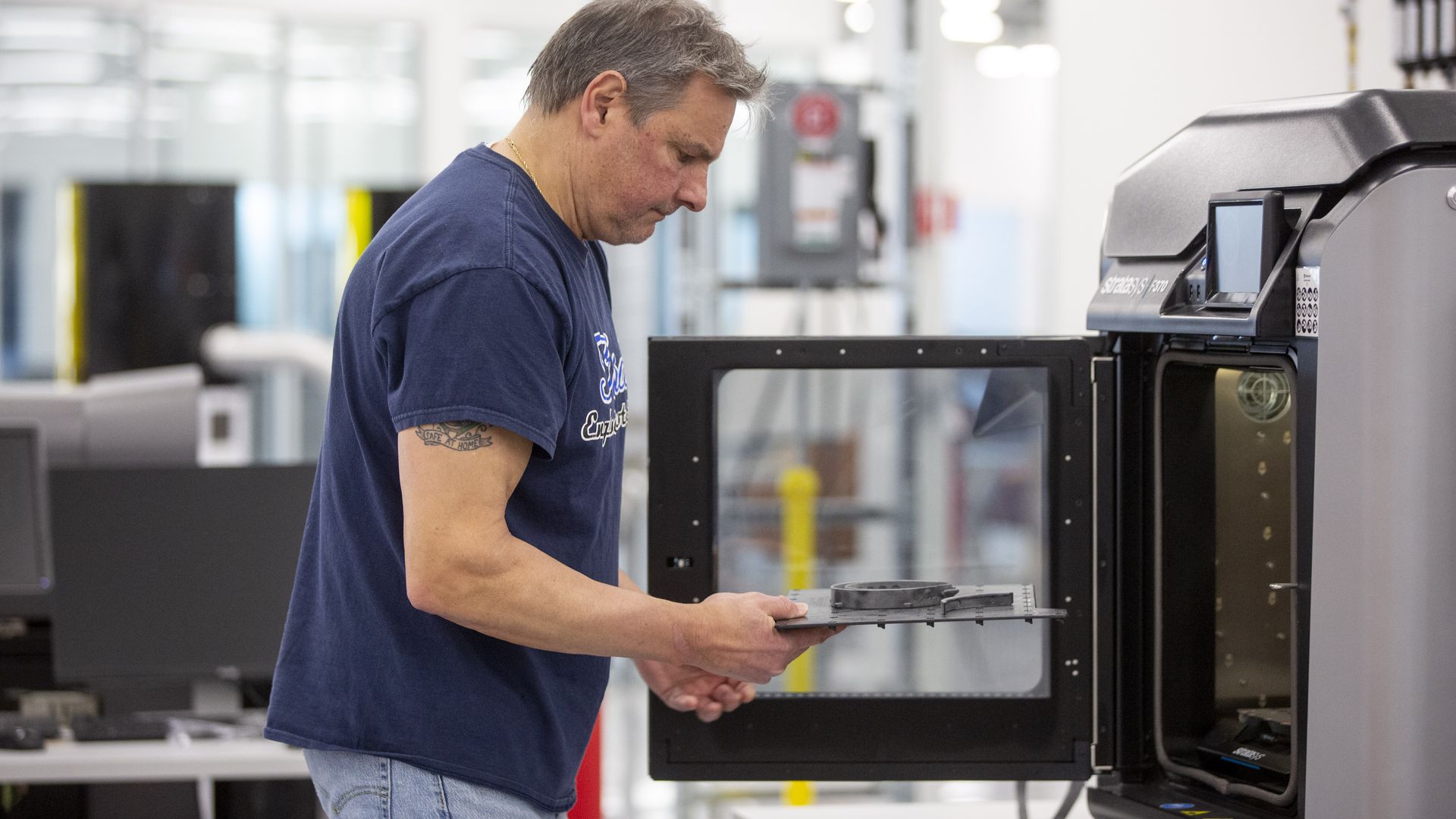

A Ford worker unloads face shield parts from a 3D printer. (Photo: Ford)

The nationwide shortage of medical equipment to fight the coronavirus pandemic seems like a breakthrough opportunity for 3D printing technology. But in this urgent crisis, its uses are limited.

Why it matters: America needs to manufacture tens of thousands of ventilators and billions of face masks and other protective gear in the next few weeks, and then distribute them in a hurry to hospitals around the country to ward off the worst-case public health scenarios.

Reality check: Industrial-scale 3D printing could help in a few scenarios, like making fast prototypes or fabricating plastic face shields, but it will not save the day when it comes to the most urgent needs, which are ventilators and N95 respirator masks.

How it works: There are an estimated 47,000 industrial-scale 3D printers installed in the U.S., according to Forbes, most of them idled at the moment due to coronavirus-related industry shutdowns.

- With the proper digital instructions, companies and even do-it-yourselfers can start fabricating objects almost immediately using a 3D printer.

- Known as additive manufacturing, 3D printing "grows" an object one thin layer of plastic — or metal — at a time.

- With multiple machines, even in different locations, it is feasible to 3D print thousands of small components fairly quickly.

- But the technology is not as fast, or as consistent, as traditional manufacturing methods like injection molding, says Carnegie Mellon engineering Professor Jack Beuth, an expert in the field.

- While it takes longer to get traditional manufacturing up and running, "with injection molding, you can outrun 3D printing pretty quickly," Beuth says.

Even more daunting are the regulatory hurdles that make 3D printing impractical for making medical device components.

- Manufacturing life-saving equipment is subject to rigorous certification protocols, which takes time.

- "You can’t just say, 'I’m going to print it, it looks good, we’re good to go'," said Beuth.

Yes, but: There is still a role for 3D printing technology to help in the fight against the virus.

- Ford, for example, is prototyping transparent face shields for medical workers and first responders, with the goal of producing more than 100,000 per week.

- Carbon, a Silicon Valley 3D printing company, is making face shields and test swabs, writes Forbes.

- HP has designed 3D-printed parts, including hands-free door openers, mask adjusters and face shields, per Forbes, and is working on parts for a field ventilator.

What's needed: Medical device companies should start working now to certify 3D printed components for backup use when the next crisis hits, says Beuth.

- "It’s not really a technical challenge," he says. "It’s the delay in introducing a new manufacturing process."