It isn't democracy vs. authoritarianism

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

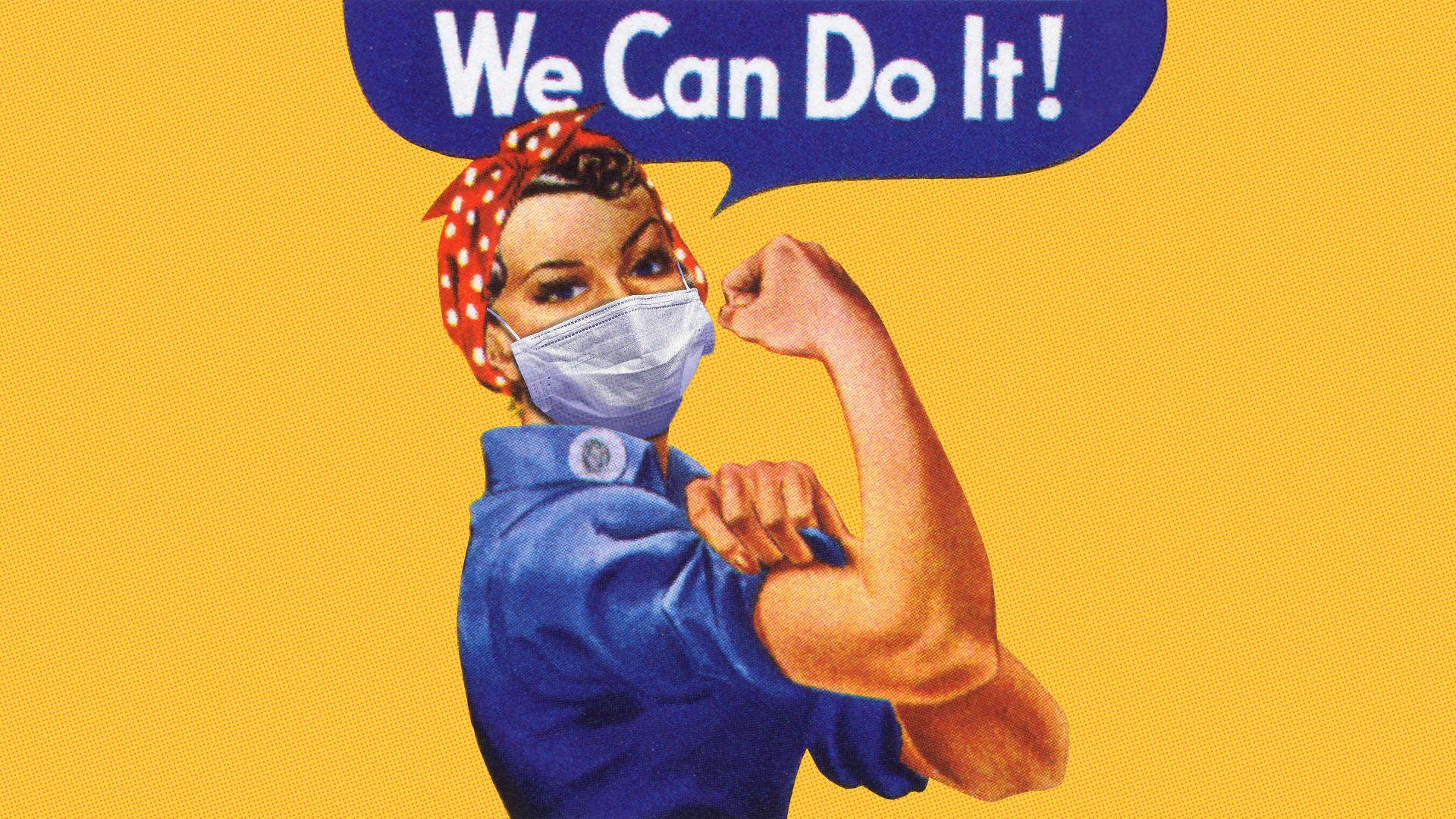

Illustration: Sarah Grillo/Axios

China's successful fight against the coronavirus has exacerbated a pre-existing crisis of confidence in Western democracies. But many of China's measures to combat the coronavirus aren't authoritarian; they are the kind of total social mobilization that happens during war.

Why it matters: In the fight against the coronavirus, as in wartime, democracies are perfectly capable of taking extreme measures when necessary.

What's happening: Growing calls for the U.S. government to take action in fighting the pandemic have resulted in a critical mass. Within a period of just days:

- Multiple states closed schools and restaurants.

- The president declared a national emergency.

- Six counties in the San Francisco area issued a shelter-in-place order to residents.

- Congress, usually gridlocked, is close to passing a sweeping coronavirus aid package.

"Wartime democracies are fearsome things," said one political scientist, who requested anonymity due to their government affiliation, in an interview with Axios. "Because you have a popular mandate that is clear and visible, which authoritarian governments can’t always rely on."

Context: Many in the West watched in both horror and awe as Chinese authorities took historic measures to prevent the spread of the virus, which emerged in Wuhan, a city of around 11 million in China's central Hubei province.

- Authorities quarantined the city, then virtually the entire province.

- Major cities throughout China shut down, and neighborhood travel restrictions were imposed, with local residential committees enforcing Communist Party orders.

- Temperature checks were conducted upon entry to many buildings all over the country, before boarding public transportation, and before delivering or preparing food.

Because China's political system is notoriously authoritarian, these extreme-sounding measures were painted as authoritarian as well.

- To be clear, some of China's measures — including a health-surveillance regime enabled by mass data collection and the forcible rounding up of coronavirus patients into quarantine zones — have clearly represented a violation of civil rights and privacy protections that would be respected in a healthy democracy.

- But when they succeeded in containing the virus, authoritarianism seemed to have won the day.

Reality check: Citywide quarantines, travel restrictions and obsessive public health checks aren't authoritarian. They're the kind of total mobilization that happens during major national crises such as war, regardless of the system of government.

- Chinese President Xi Jinping even said as much; in February, he declared a "people's war" against the coronavirus.

- Outsiders often "fixate on China’s authoritarian political system," writes Ian Johnson for the New York Times. "But it’s worth acknowledging that not all of China’s failings are unique to its political system."

- The flip side is that not all of its successes are due to its system either.

Democracies have a long history of successful mobilization, and they have mechanisms that both enable extreme policies and bring them to an end when they are no longer needed, to prevent authoritarian creep.

- During World War II, the U.S. was initially paralyzed by a domestic debate about whether to get involved at all, said Maury Klein, the author of "A Call to Arms: Mobilizing America for World War II," in an interview with Axios.

- "Things always move slower in a democracy," said Klein, because the various moving parts of government and society must first reach consensus.

But after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the U.S. jumped into action immediately and effectively, taking actions that wouldn't be possible or acceptable during peacetime.

- With government contracts in hand, private industry swiftly transitioned from producing consumer goods to war goods.

- Price controls were adopted to stem inflation.

- Mandatory blackouts were implemented in California out of fear of Japanese bombing raids, and neighborhood watches patrolled the streets at night to make sure everyone was in compliance.

- Americans supported these measures as long as they were clearly necessary.

- Yes, but: Two months after Pearl Harbor, the president ordered the internment of Japanese Americans.

What to watch: Fundamental questions about the health of our governance today and the effectiveness of our leadership suggest the United States may not rise to the occasion as well as it did almost 80 years ago.

- "Without the threats and violence of the Chinese system, in other words, we have the same results: scientists not allowed to do their job; public-health officials not pushing for aggressive testing; preparedness delayed, all because too many people feared that it might damage the political prospects of the leader," writes Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic.

- "What if it turns out, as it almost certainly will, that other nations are far better than we are at coping with this kind of catastrophe?"