This is my brain on a puppy ad

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

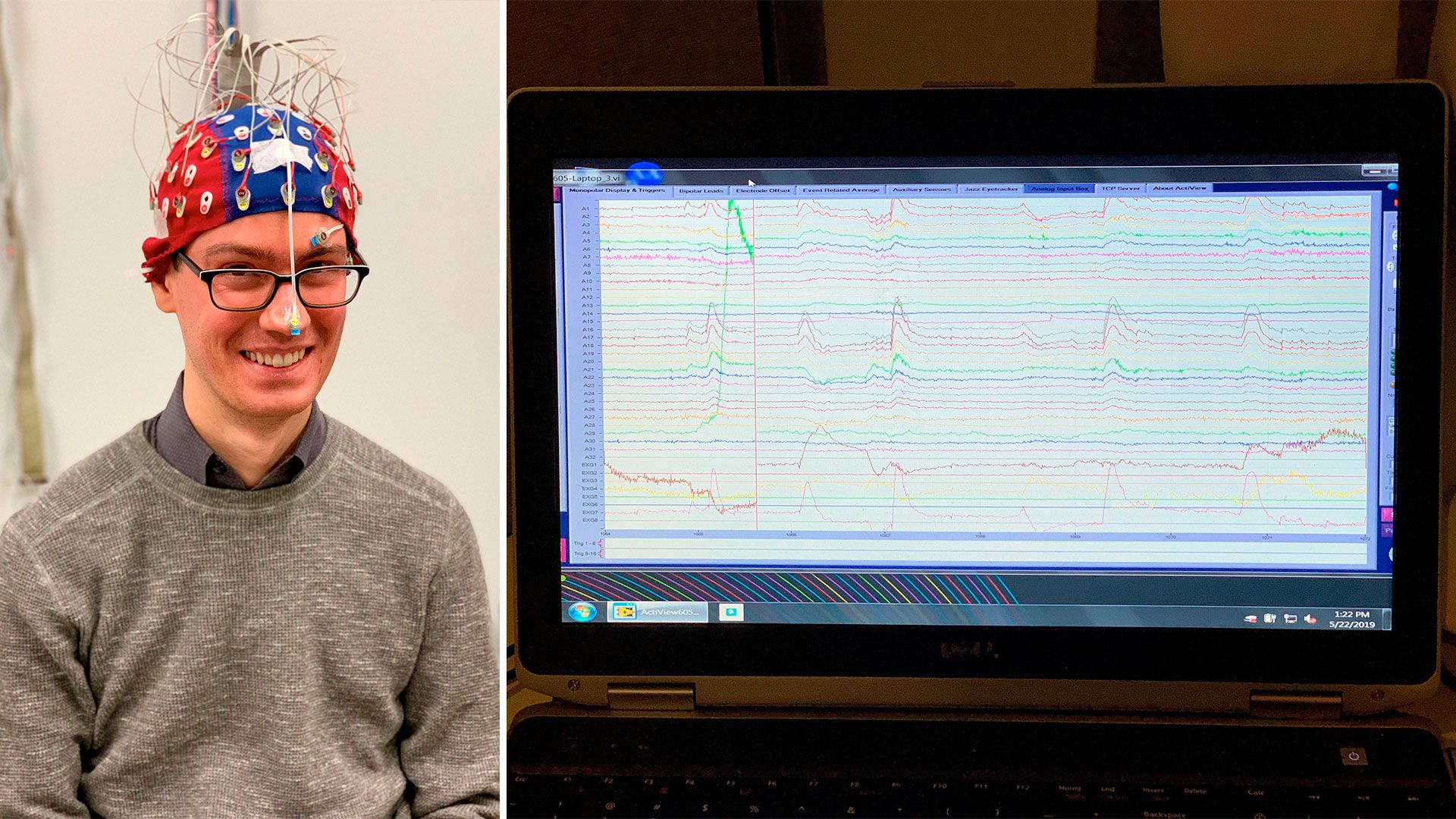

Before an EEG test — and my results. Photos: Jenna Richard/Nielsen; Kaveh Waddell/Axios

A few weeks ago, at the San Francisco office of Nielsen, a prominent market-research firm, I sat on a stool as a neurophysiologist squirted goo into holes in a swim cap she'd fitted on my head.

What happened: The goofy setup, seen above, prepared me for an EEG test — the kind subjects regularly undergo at the research firm's 16 neuroscience labs around the world.

- Bradley Vines, Nielsen's director of neuroscience, led me to one of several small rooms outfitted with nothing but an armchair and a TV.

- "You could be in Tokyo, you could be in São Paolo, you could be in Mexico City or one of the five labs in the U.S.," said Vines — in each, the same drab rooms, shielded from electromagnetic radiation, ensure the brain data captured inside is comparable.

Sensors bristled from my head. The 32 electrodes in the cap watched for changing magnetic fields from my neurons firing — 500 times a second. Cameras trained at my face watched for twitches and eye movement.

- I sat stock-still on the armchair and stared at the TV as a series of logos flashed across it one by one.

- Then words like "lovable" and "friendly" took turns on screen, followed by a video ad for adopting pets featuring a very cute puppy. Finally, the logos and words returned.

What's happening: The first series of logos and words were meant to establish a baseline — how my brain reacted to them before the TV ad intervened.

- After the ad, the second round was intended to search for a change — perhaps I now associated "lovable" with the adoption campaign.

- "Without asking any questions, we're able to see: Are the consumers emotionally motivated? Are we connecting with these ideas, communicating the brand and different concepts?" said Vines.

Nielsen wouldn't tell me about my own results, but Vines showed me how aggregate findings from test subjects watching the video led the advertiser behind it to make changes, editing out footage that lost viewers' attention and removing distractions from the screen.

This was not a dangerous exercise — apart from having rose-smelling gunk in my hair for the rest of the day.

Go deeper: Advertisers want to mine your brain