The 2020 campaigns aren't ready for deepfakes

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

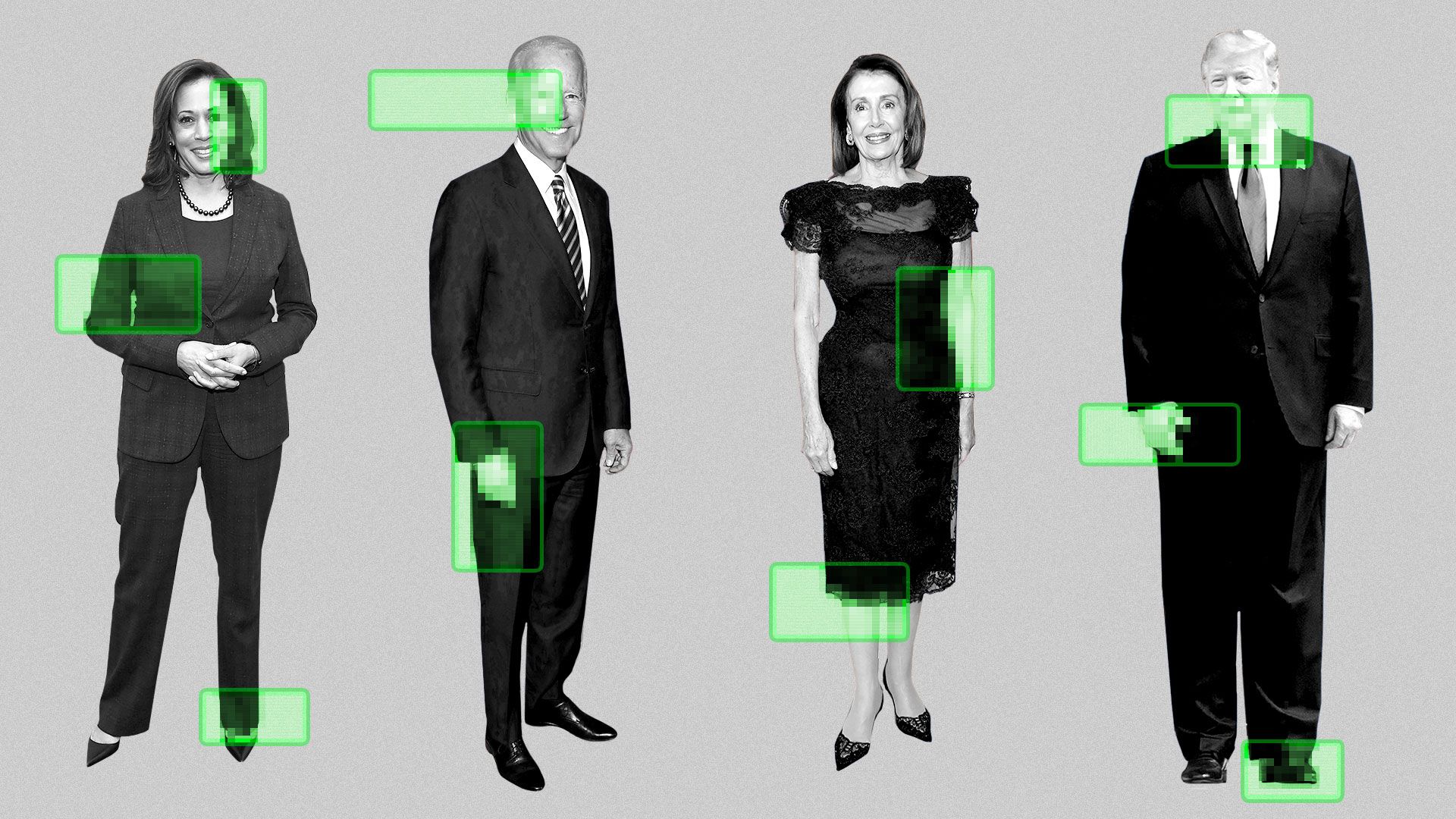

Illustration: Aïda Amer/Axios

The 2020 presidential campaigns appear to have done little to prepare for what experts predict could be a flood of fake videos depicting candidates doing or saying something incriminating or embarrassing.

Driving the news: The recent manipulated video of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was just a taste of what could lie ahead. Fake video has the potential to sow huge political chaos, and countering it is wildly difficult. And right now, no one can agree who's responsible for countering it.

Axios contacted all 24 Democratic presidential campaigns, in addition to President Trump and Republican challenger William Weld.

- Nine Democratic campaigns and the Trump campaign responded. None could point to any specific protective steps they had taken against deepfakes.

What's happening: A whole lot of buck-passing.

- Several Democratic campaigns said they rely on the Democratic National Committee for help protecting against disinformation.

- But the DNC says that job is ultimately the responsibility of campaigns. (It does send campaigns a regular email with tips and pointers on dealing with misinformation — the only concrete step we found in our reporting.)

- The Republican National Committee says it doesn't usually work with campaigns on cybersecurity.

- A Trump campaign official said the campaign "maintains constant vigilance, since the media and others online routinely distort the President’s remarks, record, and positions. We fight back when it's warranted.”

A few campaigns had other ideas about who should be responsible.

- The Julian Castro campaign fingered the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI. Contacted by Axios, DHS pointed to the FBI, which said in a statement that it investigates all types of foreign threats.

- Rep. Tulsi Gabbard told Axios in a statement that the media should play "a major role."

- And one Democratic campaign aide said the responsibility rests with social media platforms. "There's only so much that a campaign can do," the aide said.

Consultants who specialize in warding off misinformation are by and large unimpressed with campaigns' preparations for dealing with fake media.

- "We've met with a bunch of them," one consultant told Axios on condition of anonymity. "We don't feel like they are serious about investing the resources required to do anything about it."

- Experts say campaigns should have a rapid-response plan in place to deal with various kinds of manipulated media, cultivate close contacts with social media companies, and assiduously film their own candidates at every turn so that they can show when a clip has been altered.

The big picture: Do-it-yourself deepfakes are within reach of anyone with some computer savvy and a decent laptop, though the most convincing videos take extra effort. But a basic alteration — like the slowdown that made Pelosi seem intoxicated in a video that circulated two weeks ago — will do the trick, too.

These can cause all manner of mayhem, both overt and subtle.

- A video altered to show a candidate dropping a racial slur could dominate news cycles and put a campaign on the defensive.

- And mushrooming fakery could give candidates cover to call baloney on a video or audio clip that's actually real.

"Campaigns have to have a strategy in place for dealing with this," says Hany Farid, a digital forensics expert at UC Berkeley. He has characterized deepfakes as a threat to democracy.

For now, social media companies have unique power to staunch the spread of dangerous videos, images, and audio.

- But they have often failed to do so, whether by choice or because they fell short.

- It took Facebook a day and a half to solicit fact-checks and reduce the spread of the Pelosi video. It did not take the video down.

The bottom line: The Pelosi clip was a wakeup call. More videos are coming, whether the campaigns are ready or not.