Coral reefs are not the saviors they were thought to be: new study

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

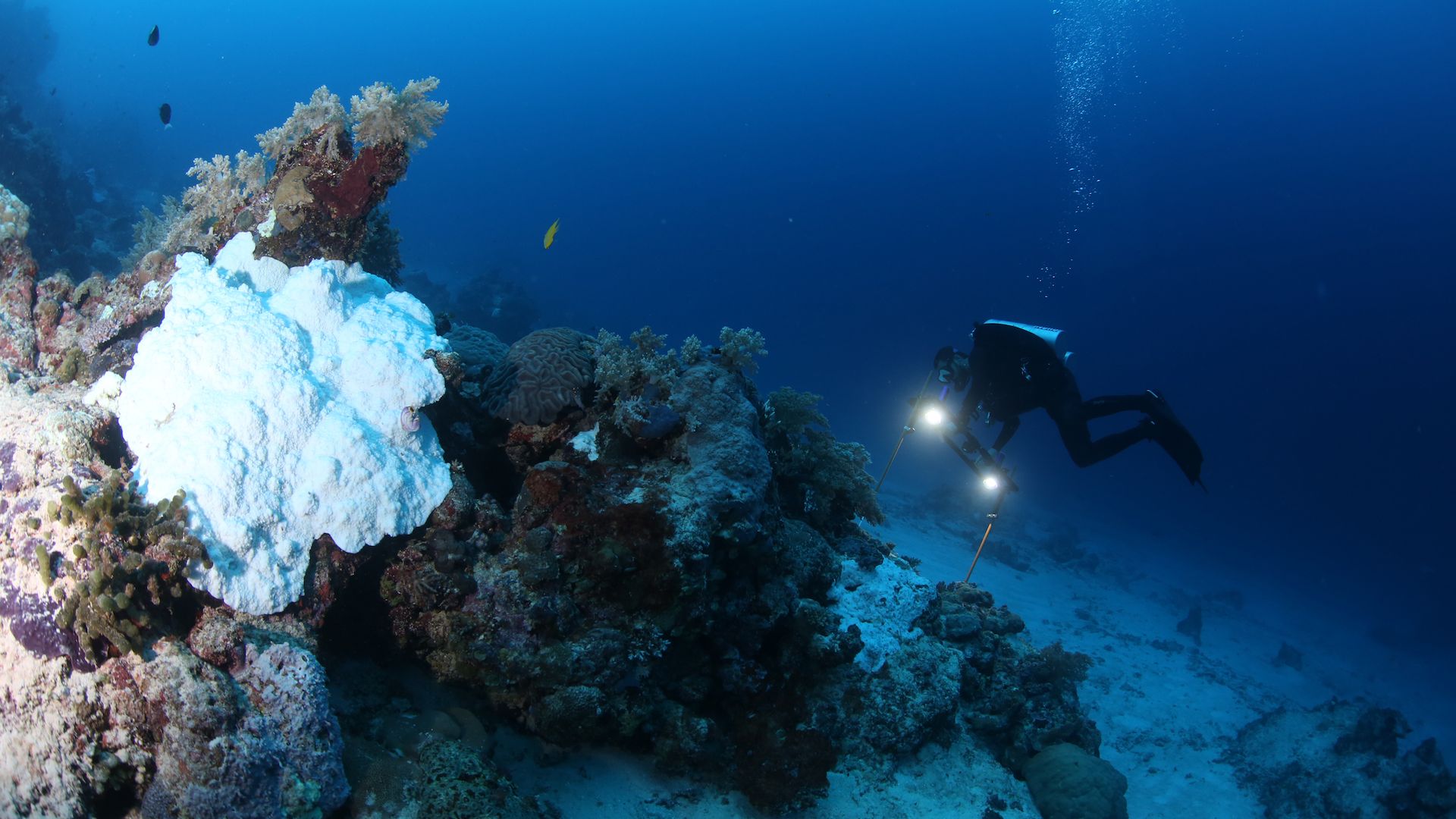

Researcher Norbert Englebert surveys a coral reef. Photo: Pim Bongaerts/California Academy of Sciences

Deep-water coral reefs may not offer protection to corals being degraded by heatwaves at the surface of the ocean, according to new research.

Why it matters: Those reefs, at between 100 to 500 feet underwater, are frequently viewed as conservationists’ best hope in saving vulnerable corals. The widespread degradation of coral reefs — which nurture creatures that provide critical food supplies for millions of people — is one of the clearest climate change-related impacts affecting humanity.

The details: The study, published Tuesday in Nature Communications, examines the extent to which coral bleaching penetrated to deeper waters during the Great Barrier Reef's devastating mass bleaching event in 2016.

- During this event, 30% of the Barrier Reef's shallow water corals died.

How they did it: Using temperature measurements at various depths at nine sites on the Great Barrier Reef and the western Coral Sea, plus surveys conducted by divers down to 130 feet, the researchers concluded that deeper depths offered some protection from the intense bleaching seen at the surface. However, this protection came with caveats:

- Initially, cooler waters moving up from deeper waters kept the deep-water corals from bleaching. But once these currents shut down as the austral summer ended, the water temperatures skyrocketed in these zones too, leading to similar temperature spikes as the surface corals were exposed to.

- The researchers characterized the impacts on the deep reefs as "severe" — 40% of the coral colonies studied were bleached, and 6% died.

- The toll closer to the surface: 69% of coral colonies bleached at a depth of just 16 feet.

- Importantly, they also found the species of corals changes with water depth. That hints at the difficulty of a leading conservation strategy involving relocating vulnerable corals from the surface to deeper waters.

"We were hoping that the fact these reefs are dimly-lit and located further away from the heated surface waters would have provided protection from the bleaching, but that was not the case."— Pedro Rodrigues Frade, University of Algarve

The context: Several studies published in the past few years raise doubt that deep-water corals can serve as refuges for coral species deemed vulnerable at the surface.

- For example, a study published in the journal Science in July, which included some of the same authors as the new study out this week, found that deep-water reefs are "distinct, impacted, and in as much need of protection as shallow coral reefs."

- Another recent paper reported reefs on the island nation of Palau have seen an uptick in bleaching events, though at different intervals and with varying severity compared to surface reefs.

Yes, but: One limitation of the new study, according to Frade, is that it does not indicate what ultimately happened to the deep coral reefs after the bleaching event. They may have bounced back, or suffered longer-term damage, like many of the surface reefs did. The research team hopes to return to their monitoring sites to check up on these corals.

According to Thomas Frölicher, a climate researcher at the University of Bern who was not affiliated with the new study, the new research also shows that scientists need to better understand local ocean currents that can control the fate of deeper reefs.

The bottom line: The new study, backed by earlier research, shows both surface corals and deeper reefs are vulnerable to heat stress from human-caused climate change.