Finding melanoma patients who would benefit from immunotherapy

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

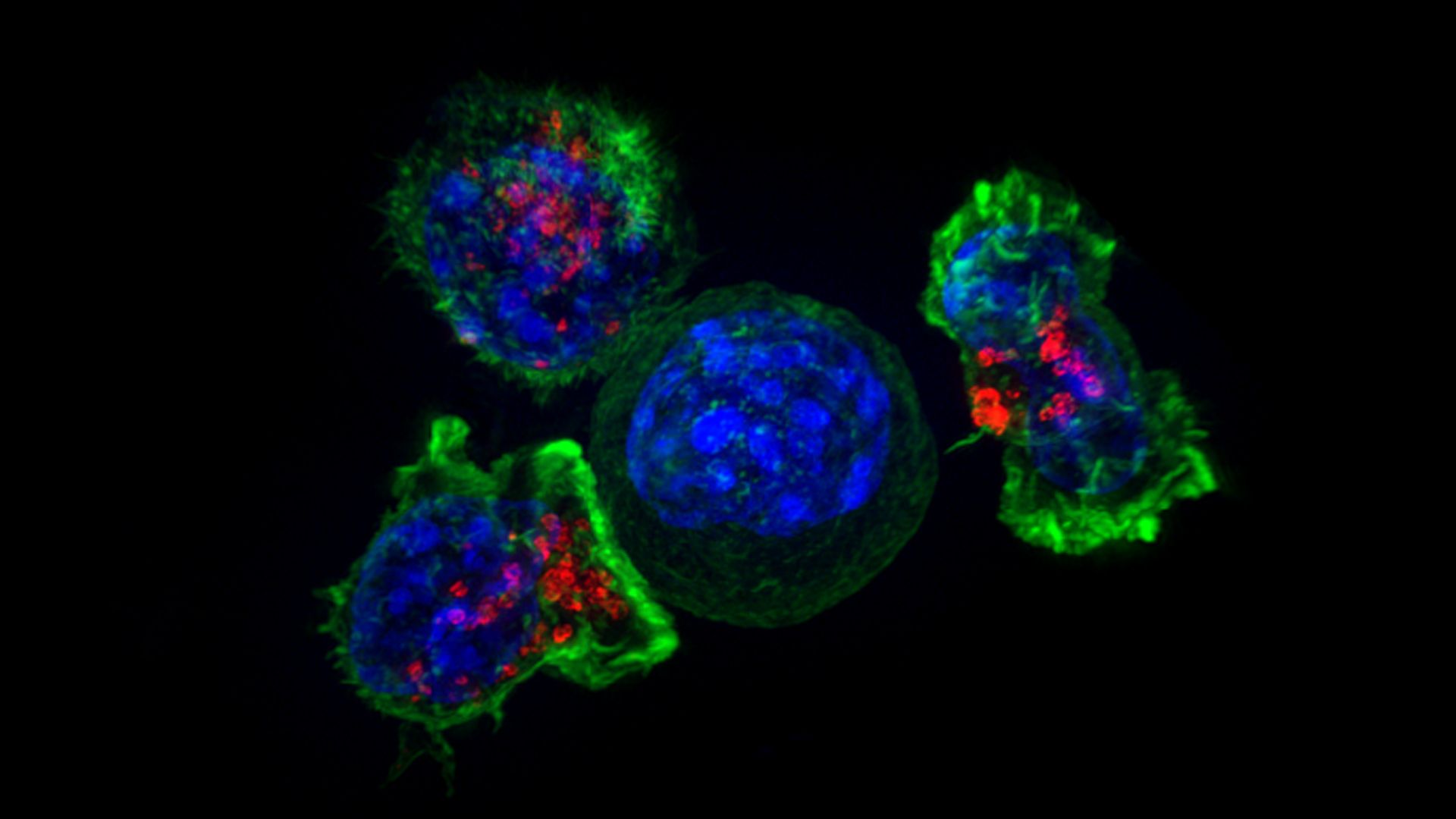

Superresolution image of T-cells (green and red) surrounding a cancer cell (blue, center). Photo: Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz and Gillian Griffiths/National Institutes of Health

A team of scientists say a biomarker test in development has shown a higher success rate than currently available tests at determining which patients with metastatic melanoma will respond to a certain type of immunotherapy, according to a new study published in Nature Medicine Monday.

Why it matters: Checkpoint inhibitors, which help the body's immune T-cells recognize and destroy tumors, have shown a range of success in treatments but also often come with serious side effects. Being able to predict if an individual's targeted cancer would respond to the immunotherapy is key to helping patients select their best treatment.

"Immunotherapy has made considerable strides in the past few years, with the advent of both checkpoint and cell-based therapies (e.g., cancer vaccines and CAR-T therapies). These are truly exciting and encouraging, but there is a continuing mission and challenge to increase the efficacy of the treatments, extend them to more cancer types, and further increase their efficacy and the number of patients that can benefit from them."— Eytan Ruppin, study author, University of Maryland

Background: Checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for treating metastatic melanoma but have had varied success. Their side effects can be life threatening, including inflammation of the lung, heart or neurologic problems.

What they did: The researchers used clinical data from 9 prior studies, plus they tested another 41 new patients (31 patients treated with anti-PD-1 and 10 with anti-CTLA-4, which are the two main types of checkpoint inhibitors for melanoma). This allowed them to evaluate a total of 297 samples.

- In creating the biomarker (a characteristic that indicates the responses to a therapeutic intervention) they decided to target a gene signature found in a type of cancer found mostly in young children. Such tumors, known as neuroblastomas, often show spontaneous regression, disappearing partially or fully.

- They took the gene expression featured in regression and created what they called an IMmuno-PREdictive Score (IMPRES) for each patient sample and ran it against the 297 samples.

What they found: IMPRES had a 83% accuracy rate, "outperforming existing predictors [which Ruppin says is just over 60%] and capturing almost all true responders while misclassifying less than half of the non-responders," the study states.

What they're saying: Mario Sznol, co-director of the cancer immunology program at Yale Cancer Center who was not part of this study, says the new research doesn't really address how IMPRES would work with patients who receive a combination of therapies, which is increasingly common. Plus, he adds:

"Although it appears to perform better than other predictive tests, there is still a small number of false negatives (depending on the threshold selected), which means that if you use this test, a small number of patients who might benefit from treatment would still be excluded from treatment."

"Regardless, the new analysis could be a very useful tool in drug development, to divide groups much more accurately into very high versus very low response rates to anti-PD-1 alone, so combinations could be tested with much more precise historical response rates."

What's next: Ruppin says more research is needed "to test the utility of these scores in a controlled clinical trial that should be designed accordingly, prospectively."

Sznol says the field still needs a "comprehensive analysis" that would involve multiple biomarkers "to produce the most accurate discriminator of response and non-response."