Scoop: Inside Google's Venture Capital "Machine"

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

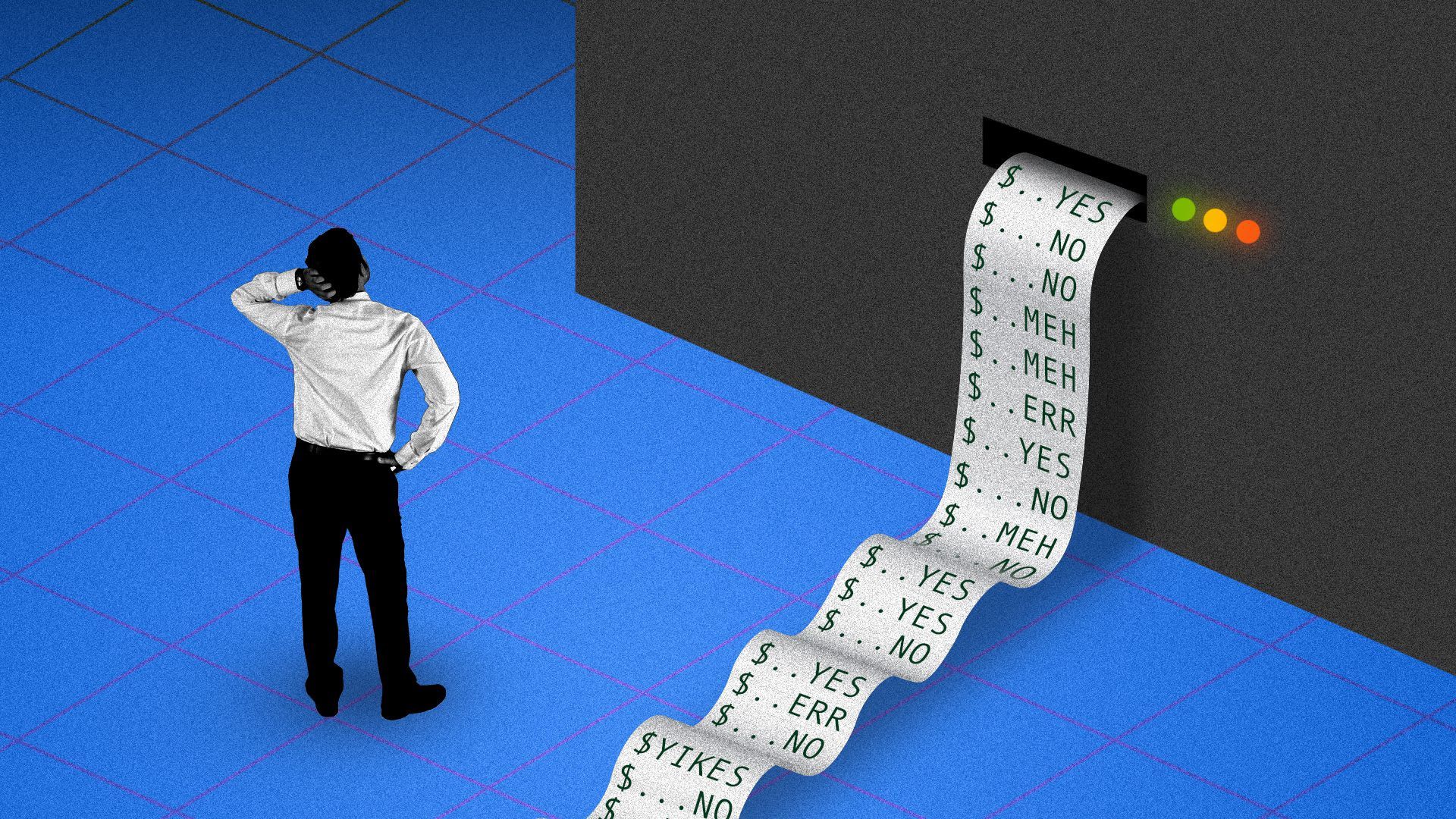

Illustration: Lazaro Gamio/Axios

When most venture capitalists want approval to make a new investment, they go to their partners. When venture capitalists at GV do it, they go to something called "The Machine."

What we're hearing: Axios has learned that the firm, formerly known as Google Ventures, for years has used an algorithm that effectively permits or prohibits both new and follow-on investments.

- Staffers plug in all sorts of deal details into "The Machine" — which is programmed with all sorts of market data, and returns traffic signal-like outputs. Green means go. Red means stop. Yellow means proceed with caution, but sources say it's usually the practical equivalent of red.

- It was initially designed and used as a due diligence assistant that could be overruled but, according to three sources, it has evolved into a de facto investment committee.

The backdrop: GV was formed in 2009 as one of the first venture firms to employ engineers whose primary job was to work with portfolio companies on technical challenges. But, in the early days, there weren't too many portfolio companies yet, so the engineers were tasked first with building a dealflow management tool dubbed "Vortex," and then with what would become "The Machine."

- Another impetus was that few of the early GV investors had much, if any, investing experience. So "The Machine" would leverage the firm's strengths (engineering) as a bulwark against its weakness (proven VC chops).

- The engineers were also asked to have "The Machine" help source deal opportunities, but that wasn't viewed as a terribly successful effort.

- The first hints of this came in 2013, when then-GV CEO Bill Maris told the NY Times: "We have access to the world's largest data sets you can imagine, our cloud computing infrastructure is the biggest ever. It would be foolish to just go out and make gut investments."

- What Maris didn't say in that piece, in part because it wasn't quite so codified yet, was the color-coding system that virtually took "gut" out of it entirely.

Inputs into "The Machine" include round size, syndicate partners, past investors, industry sector and the delta between prior valuation and current valuation. The algorithm then ranks deals on a 10-point scale, with green said to represent 8 or above.

There have been some pretty predictable problems. The first is that some GV investors have been known to try gaming the machine, manipulating inputs to get the desired results. Second, each subsequent version of the software can change the score of existing portfolio companies, which complicates follow-on investment processes.

- But the biggest may be that venture capital is as much art as science, intuition as calculation. But several GV investors tell me that "The Machine" has ripped out their guts, possibly costing them lucrative opportunities (particularly some of the more risky bets that often turn into venture's biggest wins).

- At this point, GV is not alone in using algorithms as a due diligence tool. EQT Ventures in Europe is said to have something it called Motherboard, while beleaguered Social Capital has been on a mission to largely remove the human element. But none seem as tied to the software as GV, even though a fourth source insists that it's "just a guide" and that "the partnership" still has final say.

GV declined comment for this story.

Please subscribe to my podcast, which launches Monday: iTunes. Google Play. Spotify. More.