The dangers of disease in migrant children detention centers

Add Axios as your preferred source to

see more of our stories on Google.

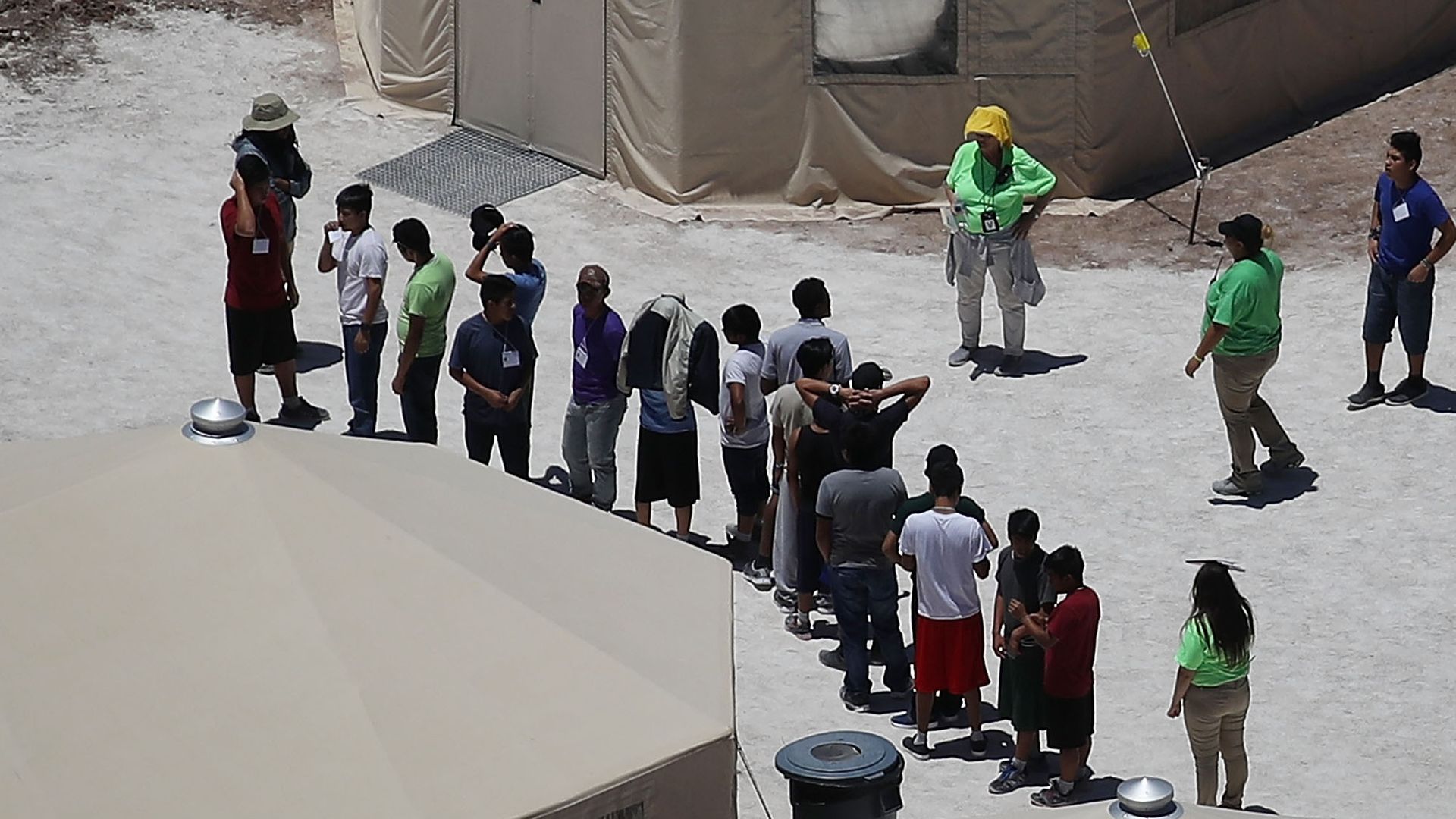

Children and workers at a tent encampment in Tornillo, Texas. Photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The detention of thousands of migrant children in U.S. government facilities — 2,047 according to an HHS estimate this Tuesday, though as many as 5,000 in Texas alone per another report — has the potential to result in widespread illnesses.

Why it matters: While there is no exact precedent for the current situation along the U.S.–Mexico border, large-scale detention of individuals, especially children, under conditions of crowding and emotional stress has historically been linked with infectious disease outbreaks.

- Upper respiratory infections and pneumonia: Acute respiratory infections were common in evacuation centers during Hurricane Katrina and also after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Tohoku, Japan (these groups included both adults and children). Reports of pediatric infectious disease illnesses among last year’s Hurricane Harvey evacuees have yet to be published.

- Tuberculosis and drug-resistant bacteria: A significant long-term infectious disease risk, including new strains that are resistant to multiple antibiotics. Children tend not to transmit TB as frequently as adults, but a number of Katrina evacuees were found to harbor other types of multidrug-resistant bacteria.

- Measles, pertussis and chickenpox: Close, crowded conditions can ignite outbreaks of these and other highly transmissible, vaccine-preventable diseases. At greatest risk are infants who are too young to have received their vaccinations. For example, a 2-month old was diagnosed with pertussis following Katrina, and measles cases have been reported among refugee populations in France, Saudi Arabia and elsewhere.

- Enterovirus: This group of viruses cause fever, flu-like illness, rash, and respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms. Transmission peaks in late July and August, and complications can include late summer meningitis.

The bottom line: The mass detentions currently underway will inevitably result in young children falling ill. Most will only contract short-term respiratory and diarrheal diseases, though some could develop pneumonia or acquire other serious illnesses. The risk of measles in young children is worrisome, because it can often result in hospitalization.

What’s next: Surveillance activities must be conducted to determine which diseases are emerging in the detention centers. There’s particular urgency to release children ahead of the summer enterovirus season.

Peter Hotez is a professor and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, where he is also director of the Texas Children's Hospital Center for Vaccine Development.